My father, Iliffe Cozens, was born in London on 13th March 1904. I wrote about his printing ancestors, The Richardson family of Greenwich, for the August issue of the magazine. However my father did not follow in their footsteps, instead he had a distinguished career in the Royal Air Force.

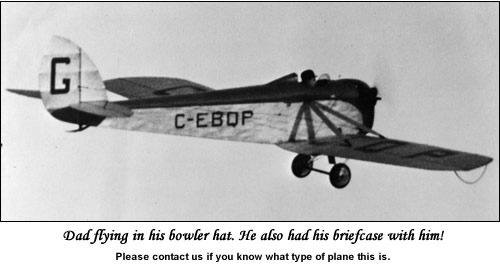

In 1923, despite intense competition, he obtained a short service commission in the RAF upon leaving St Dunstan’s College in Catford, London. He gained his wings the following year flying Sopwith Snipes, which were wooden biplanes designed and built at the end of the First World War. He was then selected for a two year engineering course at RAF Henlow, which he followed with a degree in mechanical sciences at Cambridge University.

In 1930, he was the photographer and film maker for the British Arctic Air Route Expedition to Greenland, which was to assess the suitability for a staging post for civil transatlantic flights. He was awarded the Polar Medal (Silver), for his film of the expedition, ‘Northern Lights’.

On his return to Britain, he joined the No 25 Squadron as a fighter pilot, and then went onto RAF Calshot, near Southampton, where he flew Supermarine Southampton flying boats.

After service in Iraq, he attended the RAF Staff Training College in Andover, Hampshire, in 1937, and a year later was appointed the Commanding Officer of 19 Squadron, which was based at RAF Duxford in Cambridgeshire.

They were the first squadron to receive the new Spitfire, and it was my father who collected one of the first from RAF Upavon in Wiltshire in 1938, flying it back to base after a short brief from the instructor. He made various modifications to the new aircraft, including that of preventing the pilots from loosing their knuckle skin when lowering the undercarriage. It was his involvement in the introduction of the Spitfire to the RAF which earned him the Air Force Cross (AFC) the following year.

I can remember my father telling me that the Spitfire was the first aircraft in service with the RAF which had a retractable undercarriage, and for many months a sergeant would stand by the runway with a megaphone, reminding pilots coming into land that they had forgotten to lower their undercarriage! His flying of the aircraft was officially described as exceptional, however when war broke out in 1939 he was considered, at 35, too old for active service and was instead appointed as the Assistant Director of Research and Development at Harrogate.

Eventually he grew tired of his desk job, and managed to secure the post of Commanding Officer at RAF Hemswell, the bomber base of the Polish 305 Squadron in Lincolnshire. Shortly afterwards he qualified to fly Wellington bombers and was soon involved in raids over Germany, including those over the Ruhr Valley.

He was later involved in ‘Operation Gomorrah’, the devastating successive raids over Hamburg in July and August of 1943, as well as low level night-time mine laying sorties (or ‘gardening’ as it was called) off the U-Boat bases of Lorient, Brest and St Lazaire.

My father then moved onto Lancaster bombers and it was during this time that he shot a 16mm colour film, entitled ‘Night Bombers’. After being released under the 30 year rule, it was shown on BBC Television in 1978, for which he received much recognition. The film is available to purchase on various sites on the internet, although a short clip is available on the You Tube website using this link:

Lancaster, Bomber Command Tribute.

The film starts early in the morning in an aircraft hanger, with the mechanics working on a Lancaster bomber which has come back from a night-time raid. It then follows that Lancaster and its crew throughout the day, from the loading up of the bombs, the briefing of the crew on their mission, the crew getting ready to go, and the aircraft taxiing out, which was totally stage managed by my father one Sunday afternoon, because being Station Commander he had the clout to make them practice taxiing.

The Lancasters are then shown taking off. This was shot in two parts, one where he is going alongside another Lancaster as it takes off and the second where he’s actually inside.

The footage then shows the crew flying to Germany, as well as the raid itself, which he shot through the open bomb bay doors and was intended to show new crews what a night-time bombing raid was like. This is the most iconic part of the film which is often used in documentaries, particularly the shot of the shadow of another Lancaster below his one. It is a sad fact that many crews were killed by ‘friendly fire’ when the bomb load of a Lancaster flying above, hit ones below them.

After the raid the film records the flight home, having to land by FIDO due to fog, the crew debrief and, finally, the Lancaster back in the hanger early the next morning being prepared for the following night’s mission.

He was grounded in April 1944, along with all station commanders and staff officers, after a staff officer, who had been briefed on the plans of D-Day was lost over Germany. He then served as the Senior Air Staff Officer at No 1 Group Bomber Command until the end of the war.

After the war he was appointed to several senior positions in the RAF, so that when he retired from the service in 1956 he was the Deputy Chief of Staff (Air Training). He married my mother the same year.

He then worked at British Steel’s Management College at Ashorn Hill in Warwickshire, where he was responsible for installing the mainframe computers. In those days they had their own air conditioned building with reinforced concrete floors as they were so large, hot and heavy.

He had an active retirement, being bursar of the Iron and Steel Management Training College, Vice President of the British Schools Exploring Society and president of the Arctic Club.

At the time I was still a very young child at home and remember his ‘office’ and grand piano at the back of the house, along with his workshop which housed his lathe and a huge work bench with tools, screws and nails strewn all over it. Whenever anything broke in the house the cry went up, “Daddy mend!”. He regularly attended to jobs around the house such as fixing cooking utensils, cookers and door handles, although his repairs could be quite unconventional at times.

He adored fixing clocks and mechanical things, and photography was another passion. He was the church warden for many years, as well as playing the organ (complete with his own ‘twiddly bits’).

He was always keen to have the most up to date camera, even when his sight was failing. I can remember taking him around a church flower festival and he would point the digital camera to take a photo, but then couldn’t hear the ‘in focus’ beep, so had to move it closer to his ear and then back again. I often wonder how he would have managed with modern day computers.

He revisited Greenland on the 50th anniversary of the British Arctic Air Route Expedition in 1982, and in 1984 co-authored the book ‘Bombers’, on the development of bombing.

Even in his 80s he was still very active and regularly swam and skied. We paid for him to fly on Concorde for his 80th birthday. Given his distinguished career, he was invited up onto the flight deck where he remained until the supersonic jet landed. A fitting honour to someone who had learnt to fly in wooden biplanes.

He died in 1995 when he was 91 years old. His first grandchild, my daughter, had been born six months previously, and he was so proud and happy. It is quite a thought that if she should live as long a life as him, then just three generations of my family would have covered a period of 182 years. I think that future genealogists can well be forgiven for looking for the ‘missing generation’.

Velma Dinkley

Written from material supplied by Bo the Bodger

© Velma Dinkley 2008

SOURCES

Obituary from “The Times”, 8th July 1995

Air Commodore H I Cozens

Personal memories

FURTHER

Duxford: Between the wars (1919-1938). The web page shows a photograph of my father flying a Spitfire.

Spitfire, the legend, the facts and its opponent. A fascinating film about Spitfires, in which my father appears.