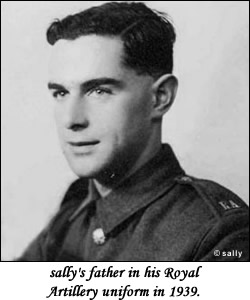

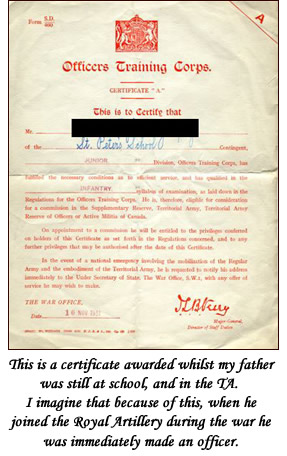

It is only in very recent years that my father, now aged 93, has talked about his wartime experiences, and I know that this is common for a great many men who served in the Second World War. It is almost impossible for most of us to imagine what they went through, and for some the memory is just too painful.

I am so grateful that I have my father’s memories, now so freely given, to add to my family history research. I would urge anyone with a relative still alive, who took part in WW2 in whatever capacity, to try to get them to open up a little. The results may astound and enthral you.

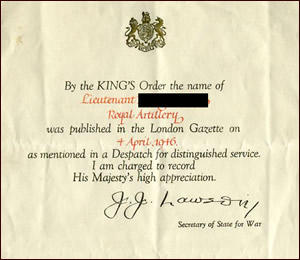

My father was mentioned in despatches, but no amount of probing, either by myself or his 90 year old sister, has made him reveal what he did to deserve it, nor will he talk about the actual fighting.

Suffice to say, at one point a shell exploded so close to him that it burst his eardrum, and whilst he never regained his hearing in that ear, he never regarded it as a disability and uses it to his advantage to this very day!

The following is a precis of his memories, which I hope will inspire you to delve into your relatives’ exploits during WW2:-

“Our unit was small, and several of us had had a comfortable life. Some men coped better with the hard regime of the army better than others, and one of these was my very good friend who was a nephew of Neville Chamberlain.

His mother was completely charming, and in her letters kept bemoaning the fact that she had lost her staff because of the war and had to draw the curtains herself!

He was godfather to my first son, and went on to higher command in the army, always generously insisting that it was his profit from my work, but that was the way of him and of many of my colleagues.

We were still in England when the Germans started lobbing over the V1s, which were projectiles started off at 320mph, but by the time they reached the South Coast they were down to about 120mph, so that once they reached London they petered out.

They were awful things as they would suddenly cut out, and that’s when you dived for cover because it meant that they were going to drop. There wasn’t a massive amount of explosive in them, but the blast in a built up area was such that all the surrounding buildings collapsed.

At that time our unit was transferred from our ordinary guns to anti-aircraft weapons in Essex, and we stayed in a holiday camp (closed of course!). It was just about possible to hit these V1s, but they were a very tiny target. The Hurricanes had more success by tilting them over with their wing tip, so that they went off course and landed in more open ground.

When we were in Belgium after D-Day, they started lobbing them towards Antwerp, so when we went to Normandy our first job, after Caen, was to search the woods for the hidden launch sites and destroy them.

Then of course, the V2 appeared, which was again unmanned. It was bigger and they couldn’t aim it quite so well, but it had more explosives. It was also ten times more frightening for people in the cities because they couldn’t hear it coming. In fact, had the Germans continued to use them, then they would have won the war. They were experimenting with one which not only exploded but emitted gas as well. These were very serious weapons.

Next came what I honestly think was the most terrifying week of the war for me. I was sent on a three week motor transport course in Rhyl, Wales, as I was to become the transport officer for our unit.

The trouble was that if people thought that you had a bit of intelligence, you tended to get picked for things like this, and it was of course on top of all your normal duties.

The Brigadier in charge of the course, in his ‘welcoming’ speech, informed us that it would be split into three weeks; gun-towing vehicles, three tonners, and finally motor cycles. He cheerily said that of course we would all have had many years of experience on motor cycles, otherwise we wouldn’t be on the course.

Well, I looked around and amongst the 30 or so of us there was one chap, who like me, went very pale indeed! I had never been on a motorbike in my life, well apart from when I wrecked my brother’s when I tried it out and attempted to change gear without depressing the clutch, thereby stripping the gears.

The first two weeks were a doddle and great fun, but then came the dreaded bike week. I was scared witless and spent the whole time shaking like a leaf whilst haring around the countryside of Wales. For me that was a terrible time!

We were parked up in Portsmouth waiting for D-Day (although in the end we went out a week or so later), when I heard that my first son had been born. I asked if I could whip up to Leeds by train to see him, then come back the same night.

Of course, any leave was officially strictly forbidden, but the chap in charge said that I could go at my own risk, but on no account was to tell anyone that he had given permission. I duly went up to Bramley, saw my newborn son for about half an hour, then caught a train back to Portsmouth, only to find that everyone had crossed to Normandy, taking my kit with them!

I was a little stressed to say the least, and in the end went to the military headquarters in Plymouth and pleaded with them to help me get across. They were very good and found me a tank landing craft which was about to cross, and I finally caught up with my unit some 3 days later, somewhere between the Normandy Beaches and Caen.

It wasn’t exactly easy catching them up, because I couldn’t really tell the full tale. I had to make up stories in order not to get the chap who let me whiz up to Leeds into trouble. When you are young, these things don’t seem so bad, but looking back on it…

Whilst we were in France (or was it Belgium?) ‘they’ decided that I should be appointed ‘Booby-Trap Officer’, because they had to have one. I was a 2nd Lieutenant at the time and myself and the Sergeant went on a course. The war was full of courses!

The instructor was very good and with ample demonstrations showed us how easy it was to fall victim to a booby trap. We left with some equipment to take with us, including a small anti-tank mine, in order to teach a little squad in the unit. In later years the Germans protected their tanks by putting something underneath so that you couldn’t blow them up.

We were also given some fuses and ignitors, so that we could have a bit of fun teaching others. I well remember that when we were in Germany, where the Parish System was very strict, the British Army had to be very careful with the Burgomasters. They did things right and the British Army had to as well.

I decided to use our demonstration mine and planted it in this field. I think that we towed something heavy across it. Anyway, the thing duly went off (it was powerful enough to send a tank flying), but what we hadn’t realised was that the field was full of potatoes and they were splattered everywhere!

My Commanding Officer and myself were temporarily court marshalled, because the Germans claimed damages, but we did get out of it on a technicality.

We only once had to use our booby trap knowledge as just before the end of the war we were parked up on the German border and about a mile away was an old French gun site surrounded by sandbags, with four guns and underground storage. The whole unit had been forbidden to go there because of the danger of booby traps.

We had two very nice Welsh miners with us, who couldn’t read or write. So we would write their letters for them and read the ones from home. Anyway, one day they went for a wander with instructions to be back by three o’clock, but by four there was no sign of them.

We had heard a large explosion, but had thought little of it because after all we were hearing explosions all the time. However, it dawned on me that the sound had come from the direction of the old gun site, so I alerted the Sergeant and we poled over there in a truck.

There, impaled on a gun, with not a stitch of clothing left on them, were these two men. I can still see it to this day. The only thing left on them was the little asbestos loop you had around your wrist with your army number on. They had obviously ventured into the underground chamber, set off a booby trap and had been shot out of it, as if from a cannon, landing on the gun barrel. It was a horrible sight.

That was when we DID use our knowledge and we searched the whole area for more booby traps and eventually found two more. We didn’t realise it at the time, but the war was just about ending, and the British Army was on the march towards Berlin, taking it rather slowly to be honest, because they had agreed to allow the Russians to go in first.

Suddenly ‘they’ decreed that ‘us Artillery’ should be transferred to Infantry and we thought that we were cannon fodder, which was a little on the frightening side. I thought “Let the amateurs go first, so that the skilled British Army can follow on!”. If we had a union we would have refused point blank. So, all of our guns and equipment, for which we had had to account every day for years, was just chucked into a field and we were issued with rifles. Just a few mind you, not one each, and we became rather unhappy infantry marching towards Berlin.

Soon we met columns upon columns of Germans marching the other way, and after the initial shock, realised that they were getting out of Berlin because they were scared stiff of the Russians. They weren’t worried about the British or French, because they knew that they would have been treated well. We then knew that the war was over. Richard Dimbleby, the war correspondent at the time, wrote an article for The Telegraph on the liberation of Belsen and was quite right in what he put. If you saw it, you would never ever ever forget it.

Our unit was the first there, but we were not allowed in for a day or two in order to give the medical people time to spray disinfectant about, and for us to have precautionary injections and medicines. God, the stench was awful when we did go in, really awful. The whole scene was terrible, it really was… ”

Here, my father stopped talking for a full five minutes. He was clearly remembering things which are beyond most of our imaginations. What to me was really poignant, was that at this point, I had not told him of my findings that some of his relatives in Germany had perished in Theresienstadt and Auschwitz Concentration Camps.

“There was not a great deal of liberating to do, as 99% of the Germans had gone and I don’t remember there being much opposition. After the medics had seen if they could save anyone, we helped with the cleaning up. We did a lot of burning and lit many fires. It was a very bad time. I don’t know if Belsen was one of the worst, but if it wasn’t, then heaven knows what the others were like.

After the end of the war, there were lots of displaced persons camps in Germany. The Russians and the Poles were all put into these camps, and our little unit was in charge of a Polish one. We had to ration them and try to keep them in order, although we had every sympathy with them if they played minor tricks on the Germans. They used to creep out of the camp and pinch a cow or two, although we turned a blind eye as long as there was no physical violence.

We also had a Russian camp and they had never seen Western life before, so used to steal out of camp and pinch bicycles from the Germans. They had the time of their lives! It’s hard to believe, but they had never ridden bikes before and they spent hours trying to master the skill with a great deal of hilarity and bumping into things. I was in charge of the Polish camp and of course they were lovely people, but oh, what monkeys!

The British Army decreed it illegal for them to have their stills (they used to make a sort of gin out of potatoes), and our Medical Officer said to us, “Now look, they have lots of parties and love to invite the British, but on no account drink anything, because if they get the temperature one degree wrong on these illicit stills then it’s poison”. They used to hide the stills in the woods and would be in tears when we found them. I felt rotten instructing the squad to smash them up. Mind you, they would creep around the back and immediately build another one!

There was a man and a girl in the camp who had arranged to marry and they asked about four of us to go to the ceremony and the party afterwards. The food wasn’t army supply as they had best steak, a couple of cows worth at least! The drink wasn’t army supply either and I decided not to partake, although my good friend the Sergeant did. He wasn’t used to it you see and he was a goner, dead by morning. Very sad.

They were great though the Poles, even though they would diddle you left, right and centre and fiddle around the rules. It was a funny situation because we didn’t honestly care if they spiked the Germans, but you had to try to run the thing properly. The Russian camp, which my mate was in charge of, well, it was absolutely terrible really.

One day the big Russian dignitaries (they could look more menacing than anybody else) came along and told us that they were repatriating the men in the camp. The British Army supplied the trucks to take them all back, but when the drivers returned they were shaken and upset. When we asked them what was wrong, they said, “When we crossed the border, all the Russian men were taken off the trucks, shepherded into a field and shot”. It happened with them all, and it was purely because they had seen the western civilisation, western life, and all its goings-on. They were just shot without a chance. Terrible. I just kept remembering the simple pleasure they took from those bicycles.

The army was interesting and I didn’t really mind it because it kept you very fit, and as long as you ate everything you were alright. The worst time was when the war was over, because they didn’t want to demob too many men at once. There was a points system and this was the only time that I got into the whisky bottle badly. You were numbered from 20 upwards, depending on the number of years you had been in and whether you were married. I was 22, which meant that I should have got out pretty quickly, about 3 or 4 months after the end of the war. I was due out in early December, in time for Christmas, and not having seen the family for so long I was excited. Then an edict came down that all officers from 22 upwards would be delayed an extra 3 months. I thought, well, it’s not because they are short of them, because we were getting loads of officers from all over the place being transferred prior to demob.

I am afraid that I became really bolshy and not very cooperative, as well as being on the bottle. I had had enough! We were stationed in a little German village, in a sort of hotel which had a bar. We didn’t realise that German beer comes up with colossal pressure and probably wasted more than we drank! It was rather cold and we had to find wood to light the fires. A little coal train used to puff into the station once in a while and once again the Bergomasters kept their eye on things, but this train had two trucks of lovely gleaming coal.

My fellow officer and myself waited until dusk, then started up our three tonner when nobody was about and offloaded three tons of coal from the train and took it back. Unfortunately, we did end up having to sign for it, because a chap turned up in the middle of the operation and we told him that we were authorised to take the coal. I signed ‘C. Smith’, and the other chap signed ‘D. Jones’. In the morning the train chugged on it’s way, minus three tons of coal, but predictably about two weeks later a notice appeared on our notice board:- “The German Authorities are looking into the disappearance of three tons of coal”. They were so methodical those Germans and they produced this piece of paper with our false signatures on. They were determined to find the missing coal and I was so worried with my demob only a matter of weeks away, that I and the other chap sat glumly awaiting the Red Caps. But, as it turned out, they couldn’t trace it to us. Maybe before I depart this life on earth, a little chit will come from the German authorities, demanding the price of three tons of coal!”

sally

© sally 2008