My great x2 grandfather, Giles Mead, was baptised in Newton St Loe, Somerset, on 11th March 1781, the second known son of John Mead, a labourer, and his wife Lucy (née Keynton), who had married on 20th July 1774. Giles’ brother James had been baptised on 5th February 1777.

According to his discharge papers, Giles joined the ‘Ninth (East Norfolk) Regiment of Foot’ as a private on 5th April 1809, at the approximate age of 31, which seems fairly old for a new soldier. The Ninth Regiment saw service in the Peninsular War, participating in battles at Busaco, Salamanca, Vittoria, San Sebastien and the Nive.

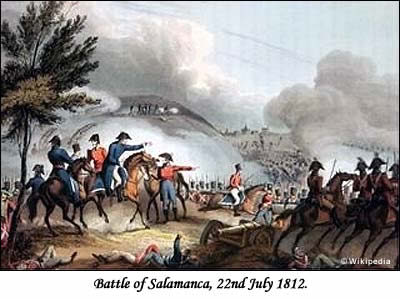

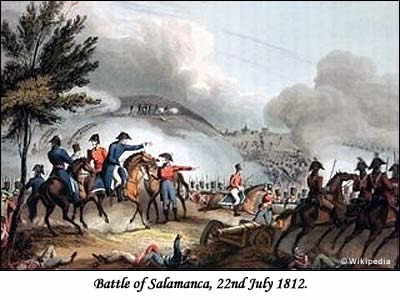

The Battle of Salamanca, for which Giles was awarded a clasp, was fought on 22nd July 1812. The night before the battle had seen a great thunderstorm and Edward Costello, a soldier in the 95th Rifles, wrote that, “it was the most stormy that I have witnessed”, and that, “not a man that night had on a dry shred”.

The French were led by General Marmont, who made a couple of mistakes which were to the advantage of the English. Firstly, he allowed the English commander, Wellington, to trick him into thinking that the cloud of dust on the horizon was the British Army in retreat. In fact, Wellington had sent his heavy baggage off on the road to Ciudad Rodrigo. As a result, Marmont inadvertently marched his army across the front of Wellington’s hidden troops.

The battle started at about two o’clock in the afternoon and went on well into the night. The French army of 50,000 fought against 48,000 British, Portuguese and Spanish soldiers.

Giles’ regiment fought in the 1st Brigade of the 5th Division, which was commanded by Major General Leith. The 5th Division saw battle against Maucun’s Division of the French army.

Two infantry divisions of the French army became spread out and vulnerable. The 1st Brigade, under Colonel Greville’s command, was deployed for attack a little after 4:45 in the afternoon. Giles’ 9th Foot were in the first line with the Royal Scots, 38th and 4th Foot.

It was reported that, “the whole advanced in the most perfect order”, and that, “the sun was shining bright upon their arms, while at intervals all were enveloped in a dense cloud of dust from whence, at times issued the animating cheer of the British infantry”.

They advanced down the hillside where they had been stationed and attacked the squares which had been formed by the French Battalion, and drove the enemy back. The cavalry then attacked the retreating Frenchmen. The 9th Foot reportedly suffered losses of 3 men dead and 42 wounded.

The battle was a total victory for the British and their allies, and demonstrated Wellington’s military superiority.

The weapon of most of the infantry would have been muzzle loading muskets (the British ones were known as ‘brown bess’), which took about 30 seconds to load. The process of loading the musket and the composition of the gunpowder made the user very thirsty and blackened their lips. The smoke from the firing obscured the vision and made the eyes sting. An additional danger was from the sparks which flew out on firing. Because of their inaccuracy, the muskets were best used in a battle situation, firing en masse at a large number of opponents.

The British Foot wore red, waist length jackets, grey trousers and black shako hats. They, like all of the British uniforms, must have been very hot under the blistering Spanish summer sun, an added hardship to the general battle conditions and the thirst from the loading of the muskets.

Several narratives were written by soldiers in the ranks which depict the everyday struggle for survival; hunger, bivouacking in the open, regardless of weather conditions, and lice. One author tells of an incident where there was no bread, so the soldiers were marched into a newly reaped wheat field and fed on the wheatsheafs instead. Lice were rampant and about the only way to get rid of them was to hold the offending item of clothing over a smoky fire. Bernard Cornwell’s Sharpe books and the television series give a good account of what it must have been like to be a soldier in the Peninsular War.

Lord Wellington’s dispatch after the Battle of Salamanca noted that the French Army was defeated by that of the Allies, “after seven hours continued firing where the infantry, as well as the cavalry and artillery of both nations did prodigies of valour”. He estimated the French loss at 10,000 to 12,000 with more than 4000 prisoners taken, as well as two French Imperial Eagles.

In fact, the losses of the British and their allies was approximately 5,000 killed and wounded, while 7,000 French soldiers were killed or wounded and a further 7,000 were taken prisoner.

The 1st Battalion of the 9th Foot participated in the ‘Army of Occupation’ of France while the 2nd Battalion was disbanded in 1815. Giles was discharged at Compeigne, France, on 24th April 1816, due to being, “unfit for further service abroad”, as a consequence of, “asthma and being nearly worn out”, to “prevent any improper use” being made of his discharge. His discharge papers describe him as about 40 years of age, 5′ 8″ in height, with light brown hair, green eyes and a fair complexion. His trade was described as ‘labourer’.

Giles returned to Somerset and eight years after his discharge married Sarah Pue, a widow, on 28th February 1824 at Bathwick St Mary in Bath. Giles and Sarah had at least one son, George born c1825, before Sarah’s death.

At some time, Giles moved to Writhlington, Somerset, where on Christmas Day 1839 he married Mary Bevan (neé Freswell), a widow about 15 years his junior.

They had a son, James, who was born on 6th April 1840 and baptised in Writhlington on 11th May 1840, and a daughter, Martha, born 18th November 1841 and baptised on Christmas Day the same year.

Giles appears on the 1841 census, aged 60, as an agricultural labourer. Ten years later he was a pauper. Under occupation the enumerator had written then crossed out ‘formerly in the army’. He died in 1851.

He had obviously spoken of his time in the army to his children, James and Martha, as even though he had left over twenty years before their births, Martha recorded her father’s occupation as ‘soldier’ on her marriage certificate.

jenoco

© jenoco 2008

SOURCES

Wellington’s Masterpiece, the battle and campaign of Salamanca by LP Lawford and Peter Young

War in the Peninsular by Jan Read

With many thanks to FTF Member Vivienne for the Somerset look-ups.