I was five years old when war broke out, and lived in Newport, Wales, a prosperous industrial and docks town. As kids, we enjoyed life spending all of our time outside playing. The weather never ever seemed to bother us, and with not much traffic, the streets were our football field, our cricket pitch and our hopscotch was drawn on the pavement.

No one ever told us to move and parents never had to worry where we were, as we always went home when we were hungry.

We also played in the fields behind our houses, but this became a building site when a factory was built to make guns, shells and war armaments, so was out of bounds to us kids. Well, that’s what the authorities thought, as we managed to find ways in to play on the bit of green that was left, but were soon moved out by the security guards.

Also on the site was a barrage balloon to deter enemy aircraft, and at night the smokescreen trucks would come and burn oil, producing smoke to cover the area and hide all the works underneath. We always went to see the soldiers that manned these vehicles for a chat and a warm drink. When we got home, Mam would tell us off for stinking of oily smoke and call the soldiers names for ruining all the washing.

At night it was so different because the only light was from the stars. Can you imagine it, no street lights and all the windows with black out blinds, with NO lights allowed to show through, otherwise there would be a knock on the door and you were told off. Although the inventiveness of kids is something else and we made our own lamps using jamjars with a cord on them for a handle and a small piece of candle in the bottom. The police and wardens would make us put them out if we were caught and tell us off. We all played together as a gang, if you could call it that, but anybody could join in, the more the merrier.

My special pal was called John and we were like twins. Our mums knew that where one was, the other one was not far away. We were playing in the street one day, as lads do, when the telegram boy arrived on his bike at John’s house. We went over to be nosey and John went inside. After a short while he came out and in a casual sort of way said that, “it was only to tell us that my dad is missing somewhere in Burma”, and we carried on playing. At the end of the war the family were told that he was killed in action, like so many more. It was a very sad time. John lost his life a few years ago in a truck driving accident, but I don’t think that he would mind me talking about us. R.I.P my friend.

Times were hard for our parents, money was short and so was food. The rationing meant that our family had very small amounts of food to last the week. That’s where Mam was a star and we never starved, although I think that she went without quite often. She would seem to make a meal out of very little and the house would be filled with the smell of home-made pies, puddings and cakes when we arrived home from school. It was wonderful, none of this shop bought stuff. The only fruit we had was local apples and plums, and the milkman would come each day with his horse and cart, carrying the milk and filling up our jugs at the doorstep.

Then there was school, which we only attended two and half days a week, because we weren’t allowed to use the upstairs of the building in case of an air raid. The boys and girls were separated in those days, so us boys went in the mornings one week and in the afternoons the next, with the girls vice versa. It did affect us, I am sure, but most of us went on to make a good life and living in later years.

Down the road from the school were the large factories that assembled all the American vehicles to send out to the troops, and they had to be tested, which was a good excuse for being late to school some days as the convoys held us up, and we mostly got away with it.

I can remember that our air raid shelter was cold, damp and smelly, but we often slept in it. When the sirens went off, mostly at night, we would all rush down the garden to the shelter and stay there until morning.

We were in there the night our street got bombed. I can clearly remember the whistling sound of the bomb as it fell. When we came out the next morning, four houses in the terrace on both sides of the street were gone and there was a lot of casualties with, I think, two dead.

We were in our shelter a few nights later when we had another near miss. A landmine was dropped and the only thing which saved us was the railway embankment behind our house. The sad thing was that many people were killed that night. My dad, who was born and brought up in the area, went to help with the rescue, only to discover that some of his friends had been killed.

Hitler’s planes were trying to hit the armaments factory but kept missing. On the hill behind our house was the anti-aircraft guns and when they fired the whole house would shake, but it made us feel better knowing that our soldiers were fighting back.

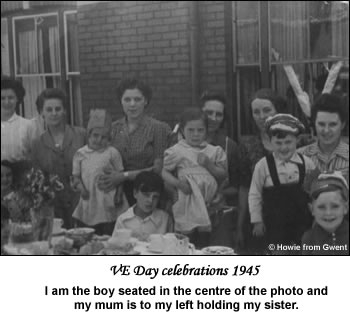

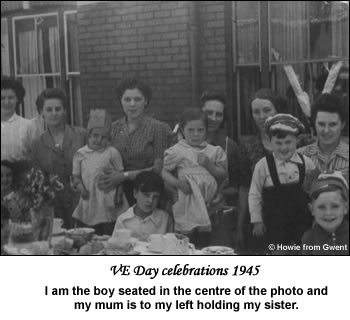

The day peace was declared we all celebrated with parties and bonfires in the street. We had a holiday from school and the lights came back on again. The men and women in the forces came home, but many didn’t, and that’s when we realised the meaning of the telegram boy’s messages.

So to all those people who gave everything for our freedom, I say thank you, and to my mum and dad, thanks for being you.

Howie from Gwent

© Howie from Gwent 2008

FURTHER READING

Children of World War 2

The Home Front