My grandmother often talked of her husband’s family’s exploits in World War One. She seemed rather obsessed with a romantic image of war; men riding into battle, swords glinting in the early morning light, some to return in glory, and others left on the battlefield who became, automatically, heroes.

“Of course, your Great Uncle Edmund had a good war. He was decorated three times. Not many people have two bars to their Military Cross”

“When your Great Uncle Clifford was killed we were all devastated. Of course, he was such a brave man. He was awarded the Military Cross too, I’ll show it to you”

No mention was ever made of my grandfather in these conversations. He hadn’t died and he hadn’t been awarded a gallantry medal, so, in the eyes of my gran, his wartime experiences didn’t deserve a mention!

Walter Henry Clark was born in April 1888 in Somerset, the eldest son of Henry Robert Clark, the Quaker schoolmaster I wrote about for the September issue [Doodles] , and his wife Mary Louisa.

He left school in 1906 and became an illustrator of interior design for various London stores such as Liberty and Harrods. When war was declared in 1914, Walter was still living in London, although he didn’t join the army immediately, possibly because he was struggling with his conscience; as a Quaker he had been brought up as a pacifist, so could have joined the Friends’ Ambulance Unit, which worked on the front line, or he could have been recorded as a conscientious objector as many other Quakers were.

Instead, on 25th February 1915, he enlisted with the ‘Devil’s Own’, a.k.a. the ‘Inns of Court OTC Regiment’. Later the same year he was appointed to a commission in the 3rd Battalion of the Dorset Regiment which was based at Wyke Regis in Dorset.

I know little about his war service abroad, except for the dates quoted in his ‘Officer’s Record of Service’ book. However, the date his first overseas posting finished after nearly seven months – 1st July 1916 – is probably significant for many of us.

The first hour of the Battle of the Somme claimed over 20,000 British lives and was one of the most disastrous days in the history of warfare. Not that you would realise this from the personal description given by my grandfather to my mother many times over the years.

He explained that he was in a trench that was very close to the German lines, and he and his men had been given orders to send hand grenades across in an attempt to disable some snipers who were hidden from view, but the distance was too great and the grenades mostly fell short.

Walter’s father was a mathematics teacher and so my grandfather enjoyed mentioning that thanks to his knowledge of Pythagoras’ Theorem, it occurred to him that if he moved further down the trench, which became gradually nearer the enemy, the distance to be covered would be reduced and their attempts might be successful.

He would finish his story, “Unfortunately, the Germans were also aware of Pythagoras and their attempts were more successful than my own!” Walter was injured mainly in the face and right arm. A bullet had passed through his right cheek, removing many of his teeth and a piece from his bottom lip, “Altering my looks much for the better”, he would later say.

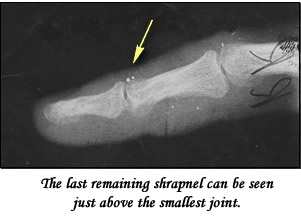

His right wrist also suffered a gun shot wound, damaging the tendons and nerves to his hand. He also had various bomb fragments lodged in his right fingers and the fingertips blown away. There was also some minor shrapnel damage to his left bicep.

It was soon after this that my grandmother stood on a railway station in London and saw a tall soldier with both arms in bandages, standing with his back to her. “I knew he would be good looking before he turned round”, she told me, years later. I think he probably didn’t stand a chance!

Walter was on sick leave for four months and was then posted back to Wyke Regis where he remained for a whole year. Unfortunately his army record doesn’t disclose his army activities during this time.

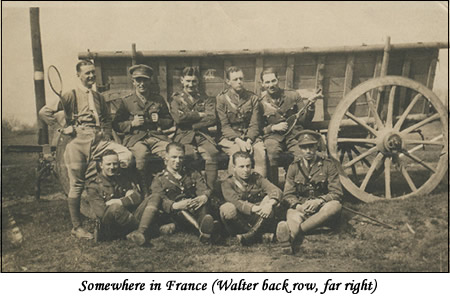

On 8th November 1917, Walter and Mai married at All Saint’s church in Wyke Regis and a few days later Walter was once again posted to France. Again, I don’t know exactly where he was or what he was doing, but nothing untoward happened to him and eventually he was demobbed on 21st May 1919.

So, back to civvy street and Walter needed a job. However, there was a problem in that his injuries had affected the use of his right hand, leaving it slightly paralysed in the fingers and unable to be fully opened because of tendon damage; not good for someone who earned their living from drawing and painting.

A lengthy correspondence with the War Office ensued, and eventually Walter was awarded a pension of £16 10s 4d per annum based on a 20% disability. This sum increased to £47 4s by 1952.

Walter returned to the world of interior design for a few years, but by 1923 he decided to retrain as an architect. His first job was as architect to the Cyprus Asbestos Company, which meant Walter and his family moving to Cyprus for five years which was easier on his remaining injuries and the warm climate eased the mild pain he suffered.

My mother remembers years later, he would sit at his desk in his office in Holborn, London, with a small toaster on the table to warm his hands as the circulation through his fingers was very poor.

Walter continued working as an architect in London until he was 70 years of age. He was self-employed and, despite a second spell in the army for the duration of WW2 when he was garrison engineer for Bulford Army Camp on Salisbury Plain, he had not contributed sufficiently for an Old Age Pension until 1958.

He then retired and moved to Adderbury in Oxfordshire, where his grandmother, Mary Buck, had lived years before. Though he enjoyed his retirement years, he never really stopped working and could be found in his spare bedroom ‘office’, drawing, painting and planning new projects right up until the day he died in 1965.

So, an ordinary war maybe, with far less suffering than so many others endured, yet the effects of Walter’s service were still evident for the best part of fifty years.

Merry Monty Montgomery

© Merry Monty Montgomery 2008

SOURCES

MoD army personnel records: UK Ministry of Defence.

The National Archives: army personnel records.

Family papers

Family photographs

FURTHER READING

The Inns of Court OTC Regiment

Inns of Court Officers Training Corps by E.R.L. Errington. Available on CD from S&N Genealogy.