As we conclude our trilogy of issues looking at the Industrial Revolution, we focus this month on the fuel that powered the new industrialised nation, coal, and its subsequent effect on the iron and steel industry.

The Coal Industry

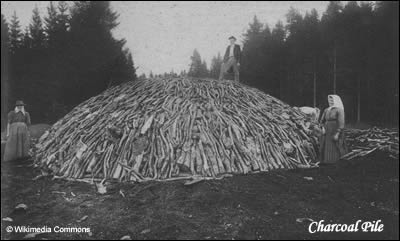

Up until the late 1700s the primary fuel source in Britain was wood and over the centuries, huge swathes of forest and woodland which once covered the country, were decimated to provide for the population. The burning of wood to produce charcoal dates back to ancient times, however it was over-forestation which led to shortages and the need to look beneath the ground for another ‘sustainable’ source of fuel.

As we have seen in the previous two issues, it was James Watt’s coal powered steam engine that laid the path for the Industrial Revolution. As more and more of these were installed in mills and factories, and with the development of the steam locomotive, there was a tremendous demand for coal.

There is evidence that coal had been extracted from the surface and from shallow ‘pits’ from ancient times, but it was industry’s insatiable demand that led to deeper and deeper mines.

Coal mining was concentrated in Lancashire, Yorkshire, South Wales, Northumberland and Durham, leading to these areas’ industrial prosperity in the 1800s. However in 1890, it was found as far south as Dover in Kent.

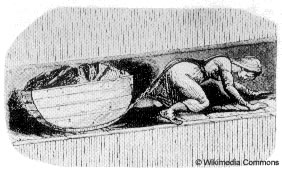

It was filthy and dangerous work, with the coal dug out or ‘hewn’ by hand with pickaxes. The miners would work semi-clothed in damp, wet conditions, crouching or lying in seams sometimes as little as two feet high.

The Children’s Employment Commission of the early 1840s found children as young as 4 years of age working down the mine, operating ventilation doors in the darkness for 12 hours a day. It also found women working alongside men in appalling conditions, which led to employment laws outlawing the practice.

The miners would start working down the mine when they were boys of around 8 or 9. If they were lucky to reach their 40th birthday, they were considered past their prime, and would try to find jobs above ground in supervisory or safety roles.

As well as managerial positions, which Meridan Line’s great x2 grandfather William Braidford 1842-1918aspired to, other jobs on the surface included carpenters, farriers, boilermakers, skilled and unskilled labourers, as well as the ‘Pit Brow Lasses’ about whom Vicky the Viking has written in her article.

However, it was those who toiled beneath the ground who were deemed to have the highest status amongst the workers of the pit, although in Vicky’s case her family chose to ‘forget’ their mining ancestors as she explains in her article, ‘A Dirty Secret?‘.

The appalling working conditions led to many medical conditions. The extremes of temperature caused fevers, the foul air led to bronchitis, asthma and silicosis, as well as eye problems such as nystagmus and the cramped working positions and heavy work caused muscular problems.

As the mines got ever deeper, ventilation and the removal of water became an even greater problem, with steam engines driving the air fans and water pumps. However the accumulation of flammable gases such as methane or ‘fire damp’, which could cause an explosion and subsequent fire, were a constant danger.

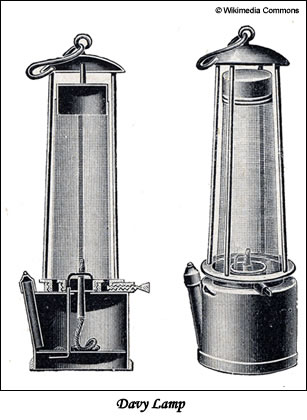

Sir Humphry Davy invented the Davy Lamp, in 1815, which would safely burn these dangerous gases within the lamp itself and would extinguish if there was an insufficient supply of oxygen, further warning the miner of danger.

The ‘father of the railways’, George Stephenson, devised his own similarly designed ‘Geordie Lamp’ around the same time. Both were a poor source of light and actually increased the number of accidents, as miners were encouraged to work in areas of the mine which had previously been deemed unsafe.

Thousands of miners were killed during the 19th and 20th centuries by cave-ins, explosions and fires, carbon monoxide poisoning and the inevitable suffocation if they couldn’t be rescued. Many were killed in accidents, such as Barbara Dodds’ great uncle, James Robson. You can read her article in this issue: Fatality at Scotswood‘.

The worst incident in British mining history was at the Universal Colliery at Senghenydd on the South Wales coalfield, when, on the 14th October 1913, an explosion and fire caused by firedamp, killed 436 men and boys. Only 72 of their bodies were recovered. The industry was under heavy pressure at the time from the Royal Navy in the lead up to WW1. Production reached its peak in 1914, which led to several similar incidents.

The harsh working conditions below ground were perhaps countered by their lives above, with tied properties, social clubs and benevolent funds. However it was the formation of the trade unions that led to the improvement of their working lives.

The National Union of Mineworkers (the NUM) was founded in 1888 as the Miners’ Federation of Great Britain and within 20 years claimed to have 600,000 members. In its heyday it was a powerful political force for workers’ rights and was involved in the National Miner’ Strike of 1912, which had an impact on the maiden voyage of the ‘Titanic’, and the General Strike of 1926.

After government control during the two world wars, the coal industry was nationalised in 1947 and run by the National Coal Board. However it was soon to face stiff competition from natural gas and oil, as well as nuclear power.

Twenty five years ago this month, Britain’s miners, led by the NUM and its leader Arthur Scargill, were a month into their year long strike against the closure of uneconomic pits by Margaret Thatcher and her Tory Government. They were forced back to work after a year of hardship and violent clashes with the police from which the industry never recovered.

In 1987, the National Coal Board was renamed the British Coal Corporation and was subsequently privatised. Today, only a small number of pits survive, but these too will close once the coal in their seams has been exhausted.

Iron and Steel

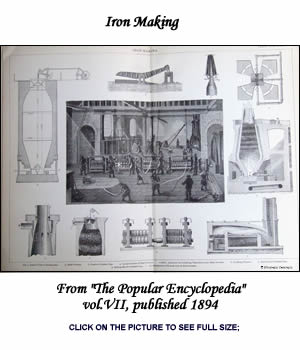

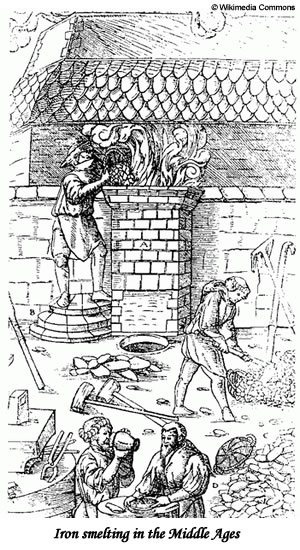

By the early 1700s, iron was smelted by the ‘bloomery’ method, where small batches of iron ore were placed in pans, covered with charcoal and blown with bellows to reach the desired smelting temperature of 1500oC.

It was a process that dated back centuries, however with over-forestation in many areas, wood came to be in short supply and the price rocketed.

In 1707, Quaker Abraham Darby was the first to use heated coal or ‘coke’ to smelt iron ore at his foundry in Shropshire and very soon he was producing cast iron in his blast furnace.

It was this ability to produce iron in greater quantities, thus reducing the cost, which encouraged others to adopt his idea and led to iron being the construction material of the Industrial Revolution.

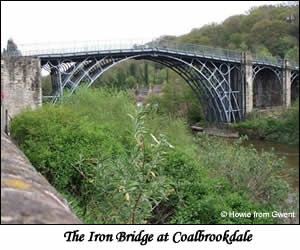

Two more generations of Abraham Darbys followed in his footsteps, each refining the craft of smelting iron ore to produce iron. His grandson built the very first iron bridge at Ironbridge in Shropshire, which was opened in 1781.

Iron was used to build the machines in the factories and the mills, the new steam locomotives and the rails that they ran on, the Royal Navy’s iron-clad battleships, as well as agricultural implements and domestic items.

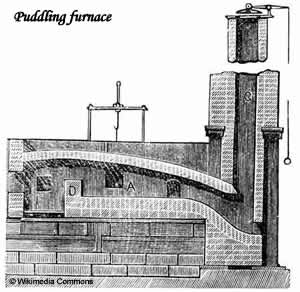

Others too were perfecting the process and in 1784 Henry Cort patented his ‘puddling’ process, which others developed and discovered that they could produce the much stronger material of steel.

Processes to produce steel had been in use for over a century, however it couldn’t be produced in sufficient enough quantities to reduce the cost and therefore increase its popularity. The problem of mass-production was finally solved in 1855, when Henry Bessemer introduced his Bessemer Converter at his steel works in Sheffield.

It was the mass-production of steel that heralded the second Industrial Revolution, leading to the development of steel ships, aeroplanes and cars. With steel replacing iron in the construction industry, it paved the way for even more ambitious civil engineering projects.

The centres of production were near to the coal fields of the North, the Midlands and South Wales, with Sheffield renowned for its steel industry.

Workers would toil for 12 hour long shifts, from the age of just 8 years old, in searing temperatures and in an atmosphere of toxic gases. The furnaces burned continuously with temperatures reaching 1650oC (3000oF).

You can just imagine the type of injuries caused through working with molten metal and heavy machinery: heat exhaustion, burns and scolds, crushed fingers, eye injuries etc. One of the worst incidents recorded was when several men fell into the furnace itself during a chance explosion.

In 1967 most of the British steel industry was nationalised, but just like the coal industry it went into decline in the 1970s and 1980s. After privatisation in 1987, it is now operated by Corus.

In this issue Guinevere writes about ‘her’ renowned Allender family of iron and steel workers, ‘The Wandering Allenders, and Helen Smith Too tells us about her home town of Barrow-in Furness, with its iron and steel connections in The Rise of Barrow in Furness‘.

Sources and Further Reading

Family Tree Forum’s Reference Library: Mining and Heavy Industry

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2009