The magazine’s theme over the last three months has been about the Industrial Revolution, and three aspects in particular – textiles, transport and coal and the iron and steel industry. Whilst Barrow owes much to the iron industry, it would not have grown from a tiny hamlet to the ‘English Chicago’ without the railway. Textiles also played a small part.

The iron industry has had a presence on the Furness peninsula for many hundreds of years, with even the monks of Furness Abbey earning money from manufacturing items. It was relatively easy to produce iron from the high quality iron ore found in Furness, so ‘modern’ methods of smelting did not appear until the early 18th century – over 200 years after other parts of England.

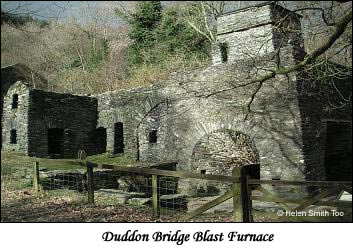

Several furnaces were built around Low Furness at that time, taking advantage of the abundance of trees to supply charcoal. The photo on the right is of the Duddon Furnace, which was built in 1736.

Ore was being mined nearer the coast, and was shipped up the rivers Duddon and Leven to the furnaces – this was cheaper than shipping the charcoal to the ore! The iron then had to be taken back the other way, but this was more usually overland.

As the industry grew, in 1782 a jetty was built into Barrow Channel, between the hamlet of Barrow and the small island called Barrow Island. This was to be the beginning of the town and port of Barrow-in-Furness. At that time the hamlet had 11 houses and by 1845 this had grown to 30, but there were now four jetties as more and more ore, iron and slate was being shipped out from Barrow. One of these jetties was owned by Henry Schneider, who was to play an important role in the future development of Barrow.

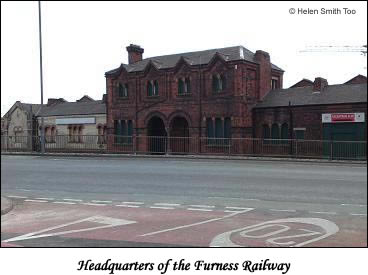

In 1846, the first stretch of the Furness Railway was built – linking the mines with the growing port. The company decided to build its headquarters in Barrow. Odd as it seems, the railway company also began the construction of the town’s dock system. The man in charge at that time was James Ramsden, who was to become the town’s first mayor. The jetties were demolished to make way for the headquarters. The building still stands by the side of Buccleuch Dock, but is mostly disused.

Into the 1850s, Barrow was still primarily a port, but in 1857, Henry Schneider, who was one of the principal mine owners, decided to build furnaces in the town, in partnership with Robert Hannay. In 1867 the town became a municipal borough – with 8,000 inhabitants. It was about this time that the first of my ancestors arrived in the town – John Brown, a tinsmith from Cockermouth.

James Ramsden was branching out from the railways and started a steel company. This merged with Schneider’s iron company to form the Barrow Haematite Iron & Steel Company, which was to become the largest ironworks and Bessemer steel company in the world. The ironworks had sixteen furnaces in operation, and steel was being shipped all over the Empire. Ramsden had very grandiose plans for the town. He was responsible for the town’s layout of streets on a grid system, with wide tree lines avenues. The rate of building new houses couldn’t keep pace with the influx of workers and their families.

From the 30 houses of 1845, the population in 1851 was 448 and by 1881 had reached over 47,000. The majority of these workers, including half of my own family, had come from the Black Country. It wasn’t the odd one or two that made the move. My great great grandfather brought his family here at the same time as four of his brothers-in-law and their families. The houses they lived in were simple ‘two-up-two-downs’, sometimes occupied by a dozen people. Many of these houses are still standing.

This was when Barrow was at its peak. The final major industry in Barrow had arrived in 1870 – the shipbuilding. The first ship was launched in 1873, for the ubiquitous James Ramsden, who was a director of the shipbuilding company. As the shipyard grew, the original iron industry started a slow decline and many of the workers moved from one industry to the other. The shipyard had a slow but steady start and even built its first submarine, the ”Nordenfelt’ in 1887. The first order for the navy was placed two years later.

In 1896 the shipyard was bought by Vickers, the name it is still generally known by. Vickers built their workers an estate of their own on nearby Walney Island, with many of the streets being named after ships built at the yard. It’s not uncommon to find Japanese tourists wandering around taking photos of Mikasa Street, named after one of the most famous Japanese battleships.

In 1896 the shipyard was bought by Vickers, the name it is still generally known by. Vickers built their workers an estate of their own on nearby Walney Island, with many of the streets being named after ships built at the yard. It’s not uncommon to find Japanese tourists wandering around taking photos of Mikasa Street, named after one of the most famous Japanese battleships.

As the 20th century rolled in the iron and steelworks continued to decline as the shipyard grew. By 1911 the population of Barrow was nearly 64,000. The outbreak of WW1 brought more workers to the town. In 1917 there were 31,000 people employed in the shipyard, but in 1922 this had dropped to just over 3,000. Between the wars other steel manufacturers had caught up with and improved on the methods used at Barrow. The ironworks finally closed in 1963 and the steelworks in the 1970s.

The only visible reminder of this period of Barrow’s past are the slagbanks, left over from the iron smelting process. Even these are half the size they used to be and are slowly being landscaped and turned into a nature walk.

The shipyard continues in its somewhat controversial role as supplier of the nation’s nuclear submarines and is starting to rise again after a slump brought about by ‘Options for Change’, a policy that saw 9,000 jobs lost in the early 1990s. Before this it was almost taken for granted that people had ‘a job for life’ in the shipyard.

Barrow has made numerous efforts to get away from its dependency on iron, steel and ships. I mentioned at the start that textiles had played a part in Barrow’s history. That was at the Juteworks, another of James Ramsden’s companies. It lasted for 20 years and, at its peak, provided work for 2,000 women, but it was unable to compete with overseas competition and closed after a fire in 1892. More successful was a papermill, now owned by Kimberly Clark and one of the largest in Europe. The town’s largest employer is now the NHS.

The town’s motto is ‘Semper Sursum’ – Always Rising. Barrow’s location on the coast means it is benefiting from the ‘green’ revolution with several off-shore wind farms under development. If the government decides to progress down the nuclear power route, it should also benefit, as it’s the only place in the country that has been commissioned to work nuclear reactors in the last 20 years.

The future could be good for this small town that usually manages to pick itself up from the blows it receives, but maybe that has something to do with the people who built it. People who left behind their old lives and made a break. It wasn’t America or Australia, but it was still a primitive little place in the back of beyond.

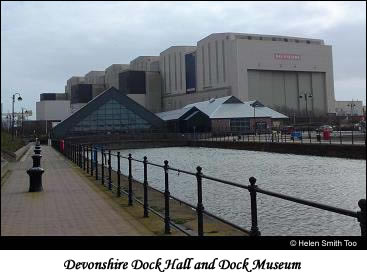

The photograph right shows Barrow past and present – the small triangular building is the Dock Museum, built over the Shipyard’s original graving dock. The massive structure behind is the Devonshire Dock Hall, built for the manufacture of the Vanguard class submarines in the 1980s.

Helen Smith Too

© Helen Smith Too 2009

Sources

Barrow and District by F. Barnes, published 1951.

Personal knowledge and images