I suppose many of us have found odd coincidences between our lives and those of our distant relatives.

As a young accountant I worked for a company that operated several factories processing lead and making lead based products, which I had to visit. One that I visited regularly was at Elswick, Newcastle upon Tyne. The works was on the banks of the Tyne close to the centre of town. When I went there, I knew that my maternal grandmother had come from a coal mining family in Northumberland, but I have since found other roots in the north east.

My mother’s great grandfather, Joseph Brumwell, who was born in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1807, came to London in about 1830 to work as a tailor. His family had been farmers and lead miners in Weardale, County Durham, throughout the 17th and 18th centuries, but several of the children had moved away to the local towns – mainly ending up in Newcastle.

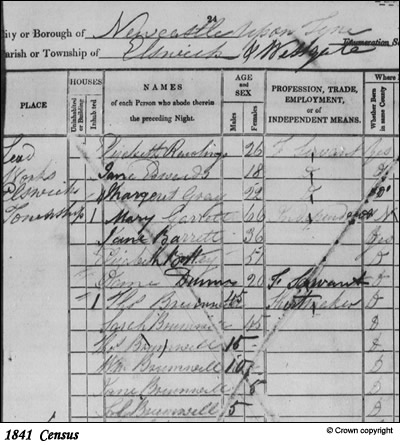

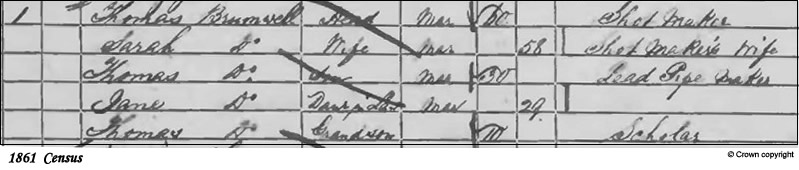

One of his cousins, Thomas Brumwell, was working in 1841 as a shot maker in the Elswick Lead Works, and was living with his wife and five children at the factory, along with ten other families including the two families who owned the works. A century later this accommodation was being used as the office building that I worked in when visiting the factory.

While Thomas was at the works it made a range of other products: White lead (lead carbonate) and red lead (lead oxide) which were used to make paint; sheet lead which was produced by passing a cast plate of lead through a pair of rollers, which were adjustable to give the required thickness of the finished sheet; lead pipe which one of Thomas’ sons, also named Thomas, made on an extrusion machine where the lead was pressed through a die to give a length of pipe. The works was originally on two acres of land, but expanded to some thirteen acres by the mid 19th century.

The manufacture of lead shot was a simple process which had been patented in 1783. It involved dropping molten lead, to which arsenic had been added to make it more pliable, from a height through a sieve into a vat of water. As the lead fell it formed perfectly spherical droplets which solidified as they cooled before reaching the vat. The water completed the cooling process and also served to cushion the fall. The size of mesh in the sieve determined the gauge of shot produced from musket balls to bird shot. The shot produced wasn’t just for use as ammunition or weights, as some was used as a way to add easily controllable and dispersible amounts of lead into various alloys.

The shot tower at Elswick was built in 1797 and was 174 feet high with a working platform inside 150 feet above the top of the water vat. It was brick built with a cupola and access to the outside from the platform. The shotmaker could at least have access to some fresh air by eating his lunch while sitting with his legs dangling over the side of the tower. How fresh the air would have been is debatable as apart from lead works, there was also an iron works, a colliery and, by the 1840s, a railway line around the site. Soon after construction the tower tilted which made it unusable but this problem was resolved by digging under the high side until the tower dropped back to an upright position.

Thomas had to climb the staircase which ran round the wall of the tower each day and then haul the lead, arsenic and the fuel for the melting pot up to the platform. He would have to keep a fire burning under the melting pot all day and mix the arsenic into the molten lead. A ladle would then be used to scoop the white hot toxic mixture out of the melting pot and pour it through the sieve, mounted over a hole in the centre of the floor, down to the vat of water below. Labourers at the bottom of the tower then scooped the shot out of the vat and put it into revolving drums which graded the shot by size and separated any misshaped pellets. The shot was then to be tumbled in another drum with black lead (graphite) which gave it a polished finish.

The conditions were hot, dirty and noisy. The process of dropping was described as being “accompanied by a sound resembling a fusillade of musketry from two companies of volunteers”. Thomas’ only contact with other people during a working day was by shouting down the tower between drops. He continued this work into his 60s and died in 1862.

The shot tower continued to be used until 1951, and stood until the late 1960s when it had to be demolished on safety grounds. The use of such towers became uneconomic with the development of machinery which could produce shot without the high cost of building and maintenance.

The factory which had opened in 1778, finally closed in 2002.

rkic

© rkic 2009

Sources

A booklet ‘Elswick Lead Works – over 200 years invested in the future of Lead‘ published in 1980 by Associated Lead Manufacturers Ltd.

Bygone Derbyshire: Shot Tower dominated Derby skyline

Personal memories.