I spent most of my childhood growing up in an East Lancashire mill town. The tall winding wheel at the area’s last coal mine, on the edge of town and several miles away from my home, was only seen from the top deck of a bus on a rare visit into Manchester. The pit closed in 1959 but the pit head buildings and the landmark winding wheel were not demolished until late into the 1960s. The area has since been redeveloped into a retail park, and the only memory of the area’s industrial heritage is in its name.

My dad and my grandfather were both in the police force, and consequently I had no real interest in the history of coal mining. Indeed, my dad told me that his uncle Percy’s research into our family roots had shown them to be farmers in Swaledale. What I have since learned, however, shows that he omitted to tell me the story of three generations of the family, leaving Swaledale to settle in Northumberland, where my grandfather was born in 1899.

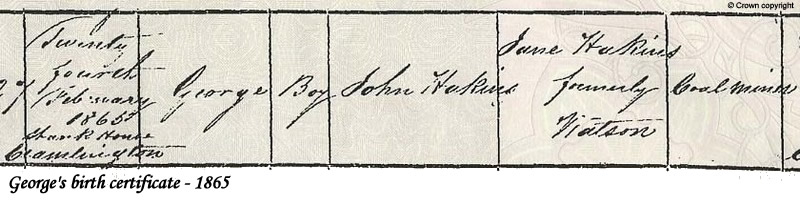

I knew my great grandfather George had been a soldier, and I had been told that his father John had also been in the army. It never crossed my mind that the boys would have had to go out to work for several years before they were old enough to enlist. Perhaps the warning bells should have started ringing when I got my great grandfather George’s marriage certificate from 1894, in India with his regiment. Both bride’s and groom’s fathers were given the occupation ‘Butcher’. At least, armed with their names, I could pick them out on the censuses – not an easy task as the surname, although rather unusual, is often misspelt. George was abroad in 1891: I later found his enlistment papers showing that he had joined up in 1886, when he was 21. Imagine my surprise when I found him in 1881, aged 16, working as a coal miner. He was living with his married half-sister and her family, and two of his younger brothers, one of whom was also working down the mine at the age of 14. Their mother, I later discovered, had died in 1878, leaving 6 unmarried children still at home. I do not know what happened to George’s father John.

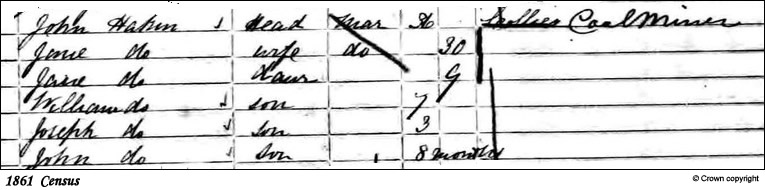

Tracking the family backwards was fairly easy once I had the names of several of George’s siblings. I discovered that all his brothers had gone into the coal mines, and so had his father John and all five of his brothers. I have absolutely no evidence at all that John ever worked as a butcher and indeed for a while I even wondered if it was a Northumbrian dialect term for a coal-face worker!

John was the third of twelve children born to William and Margaret – eleven of these survived to adulthood. William’s roots are in Swaledale, where he married in 1821. Their first three children were baptised – and one buried – in a small chapel at Marrick, in the heart of the lead-mining area around Reeth. Combining information from the IGI, birth registrations and the censuses (which were not always accurate) it was fascinating to plot the various locations where the family lived after they moved away from Marrick. William and Margaret had the usual child every two years or so, and the locations of the births showed a steady progression northwards from Barnard Castle, just a stone’s throw over the moors from Marrick. On the 1841 census they are in East Thickly, near Shildon. They moved steadily through Durham to Newcastle and then Cramlington, where my great grandfather was born. William himself died in Cramlington in 1856, aged 59, of “hydrothorax” – a lung condition probably related to, or exacerbated by, his occupation.

William’s and later John’s families seemed to move perhaps 5 or 10 miles or so between children, and I later realised that this was probably because of the ‘bond’ system in use. In those days, a miner would contract to work for a particular pit for exactly one year – April to April – and he would move on each year if he felt the wages or conditions were not satisfactory. The cost of the removal was usually met by the new employer, who also provided accommodation. Certainly my ancestors seemed to have a good survival instinct – or perhaps they were just really lucky – as I have not found any cases of any of them dying in mining accidents. Interestingly, after my great grandfather was born in February 1865, the family’s next appearance is rather further away, in Warkworth, in 1867.

In an earlier magazine (September 2007: From Cornwall to Northumberland), Geordiegirl wrote about her grandfather moving from Cornwall to Northumberland to work in the Cramlington pit after many of the local miners were evicted following a strike in 1865. I wonder if my family moved away from Cramlington because John was one of the striking miners?

On my great grandmother’s side, her father Joseph had been born to a cattle dealer in a very rural part of Northumberland, and being the third son would not have had any expectations of inheriting any property. He married into another farming family, but again as his bride was well down the pecking order, there was no family money, and in the mid-19th century no real chance of making a good living from the land. So after a few years ekeing a living as a gamekeeper, he next appears on the census having moved forty miles away to the coal fields of Durham. The only mention I ever found of his being a butcher appears in a newspaper advertisement for a missing dog, two years before he married. It seems that in those days gamekeepers were often butchers too. So at least my great grandmother hadn’t been too economical with the truth on her marriage certificate when she described her father as a butcher. Joseph died of phthisis in 1889, aged only 50, a testament to the unsuitability of a rural upbringing as preparation for working underground. Neither of Joseph’s sons followed him into the mines.

I was saddened to see so many young deaths, obviously due to the poverty, and cramped and insanitary conditions conditions these large families would have had to endure. A trip to the living museum at Beamish gave me an insight into just how they might have lived and worked. The museum is fascinating, though this is obviously a sanitised version of what things would have really been like then. The miners’ cottages were so small, it is hard to imagine a family with 8 or 10 or more children, from babies to teenagers, living, eating and sleeping in only three rooms. I visited the coal face too, and tried to imagine what it would have been like in Victorian times, working by candle-light – and having to buy your own candles too – bent double for hours on end, breathing the thick black dust.

An even better insight into some of the conditions of earlier times is given in an exhibition at the National Coal Mining Museum near Wakefield. Here some of the findings from the 1842 Royal Commission Report into the employment of women and children in the mines have been vividly brought to life in a series of tableaux. The report itself is available in the library there and makes fascinating, if sometimes heart-rending, reading. I came away from these visits with a new-found respect for what must have been a really hard way of life, grateful for the ease and comfort of modern living.

My great uncle died before he would have seen the 1881 census, so I have no idea if he had ever known about his father’s humble origins. Percy was a school master with a fastidious nature and would not have made up stories about his ancestors: whether he was guilty of sin by omission is another matter. I find it rather strange that my father told me his ancestors were farmers in Swaledale. I have traced them to a small hamlet in the middle of the lead-mining area, and I think it unlikely that an entire family would leave the Dales at the time of a major depression in the lead industry, to move into the Durham coal fields, had they been engaged in working on the land. Our surname appears in old lead-mining accounts of the area dating from the 17th century, and it is probable that my late 18th century family is directly descended from these earlier lead miners. I am saddened that my father never mentioned his family’s mining heritage, which shaped so much of their lives. Was it really such a dirty word in the latter part of the 20th century?

Vicky the Viking

© Vicky the Viking 2009

Sources and Further Reading

Marrick & Hurst Lead Mines background: Swaledale – its Mines and Smelt Mills by Mike Gill