Once we had really gotten into this family history stuff, the elderly aunts began telling us of some of the long-forgotten events in the family. Some turned out to be little more than just tales, made rather taller in the telling over the years. But usually behind the story was a grain of truth, so we set out to find out what really happened to ‘Auntie Norah’. Norah was my husband’s great aunt, the third of seven children born to John Hunt, of Irish immigrant stock, and Mary Gaskell, the wayward daughter of a canal boatman from Cheshire. She was born in 1904, and we were told that she had been scalped in a nasty accident at the local pit when she was still quite young. So I looked up her death registration – March Quarter 1923 – and sat back to await the outcome.

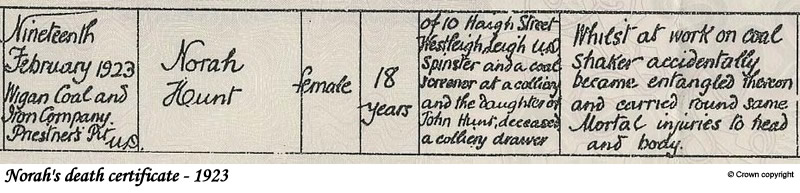

The certificate confirmed the facts as related by Great Auntie Nellie, who was her cousin. Norah was 18 when she died, and the certificate gives her place of work, her occupation (coal screener) and confirms the address we have for the family. The details of the cause of death are not pleasant reading:- “Whilst at work on coal shaker accidentally became entangled thereon and carried round same. Mortal injuries to head and body”. As the informant was the coroner, the next step was to check the local papers for details of the inquest convened to investigate the accident.

We struck lucky in that relatively full and virtually identical accounts were given in two local papers. It appears that Norah, in the manner of all the local girls, wore a shawl. While she was bending over the shaker – a sort of mechanical sieve driven by a conveyor belt – her shawl had become caught up in the machinery and dragged her onto the shaker. As it went round she became more and more caught up in it. The newspaper report does not say whether she was actually scalped – as Auntie Nellie had told us – but it was a horrific accident nonetheless and must have been dreadful to witness. A doctor was sent for but he was unable to save her, and life was declared extinct. The certificate records her place of death as Priestner’s Pit, Leigh.

Nellie also told us that the mine owners – the Wigan Coal and Iron Company – paid compensation to Norah’s widowed mother, though we have as yet not been able to substantiate this. Nellie suggested that the compensation was used to set Norah’s mother in business running a general store and sweet shop – though we think the shop may have pre-dated the accident (roll on the 1921 census!). Certainly the shop was at the same address where the family were living in 1911, and remained in the family until the 1960s.

It was somewhat surprising to find a woman as the victim of a mining-related accident, and certainly as recently as 1923, but there is a long tradition of women working at pits. Before the publication of the Royal Commission Report in 1842, it was not uncommon for women and children to work underground, particularly in the major coalmining areas of West Lancashire, Central Yorkshire, South Wales and East Scotland. Wages for women working on the surface were about 6 or 7 shillings a week but those working underground could get 2 or 3 shillings a week more. Most families lived on subsistence level wages only, and the loss of even part of their income put many into extreme financial difficulty. It was a matter of economic necessity for women to work, and the law prohibiting women from working underground was not received well. In the Wigan coalfields, in particular, the law was ignored for several decades by the colliery management, who of course also had an economic interest because the women were cheaper to employ. The law did not, of course, stop women from being employed in equally heavy, dirty and dangerous tasks above ground, again for a fraction of the wages the men received.

Although the work was hard, it was a popular occupation for young girls – indeed it was possibly the only job available for many of them – and it paid better money than the cotton mills or going into service. In the Wigan area the practice of women working at the pits continued into the 1960s, despite several attempts by parliamentarians and militant groups. The women were finally made redundant only by the increasing use of mechanisation.

In Lancashire, these women were known as ‘Pit Brow Lasses’ and were employed on a variety of tasks at the pit head. Some emptied the coal tubs or loaded the waiting railway wagons or barges. Others, like poor Norah, screened the coal that came up from the face, breaking up the larger pieces and removing stone and other impurities. Many accounts suggest that these girls were much fitter and healthier than mill-girls, as they worked outdoors or in an open-sided shed, and got a lot of physical exercise. The job certainly required both strength and stamina, as a fully-laden coal truck could weigh 7 or 8 cwt (about 400-450 kg), and the girls working on the screens frequently had to break up large lumps of coal or remove pieces of stone weighing 20lb or more. The nature of the work demanded suitable clothing, and it was common for trousers – or breeches – to be worn.

Towards the end of the 19th century, possibly as a concession to femininity, the breeches became shorter (knee-length) and were covered by a short skirt which was tucked up while the girls were working, but let down when they walked to and from home. The practice of wearing breeches gradually died out during the first part of the 20th century, and was replaced by a longer skirt, covered with an apron. The girls wore a cotton shirt, often a cast-off from an older brother, and sometimes a waistcoat in colder weather. On their heads they wore a padded cotton bonnet to keep the coal dust out of their hair; again this tended to be replaced by a headscarf or shawl by the latter part of the 19th century. The shawl became a trade mark in some collieries, where certain colours or patterns such as tartan were worn. The shawl also provided additional protection from the weather.

Everyone wore clogs – in some areas clogs were still more common than shoes well into the 1950s, even on women and children who were not working and so did not need the protection of sturdy footwear.

Because the pit girls were considered such a fascinating subject, they feature in many articles of the period and are well documented. There were also several photographers of the time who took a particular interest in capturing the girls in their working attire. Whether the fascination stems from a prurient Victorian attitude towards their distinctive and somewhat unfeminine garb, or the notion that physical hard work of this nature was degrading to their sex, is unclear. Some who objected to the notion of these women suggested that their “rough dress lead to rough morals”. However, contemporary records indicate that the women liked their work and did not consider themselves in any way demeaned. They took pride in dressing up in the evenings, and it is said that many men, including the colliery manager, failed to recognise their co-workers when they were attired in all their finery.

My husband grew up surrounded by coal mines; the pit head buildings and winding wheels being familiar landmarks. The chimneys belching out their streamers of grey smoke were constant sights, and the thick, acrid taste from the coal fires was always in your mouth. He has several generations of coal miners in his family tree, including his father who also went underground for a few years after his National Service. We have become used to seeing census entries showing the menfolk working as miners, but had tended to ignore the occupations of the wives and older daughters in these households. On re-examination, we have several of these women working as pit brow lasses – coal drawers, pickers and screeners. All of these occupations are easily disregarded as just mere words on a census page, until they are brought sharply into focus by first-hand accounts from these women about their life and times. Without these articles and photographs, these people would just be names on a page.

Family history never ceases to amaze us, with so many forgotten stories just lying waiting to be rediscovered. That’s what’s so fascinating about this hobby: you never know where you will end up next.

Vicky the Viking

© Vicky the Viking 2009

Sources & Further Reading

Inquest report ~ Leigh Journal 24 Feb 1923

Wigan Album: Colliery Lasses / Pit Brow Girls

Some of the text of the 1842 Royal Commission Reports is available at The Coalmining History Resource Centre: 1842 Royal Commission Reports

By The Sweat of their Brow: Women Workers at Victorian Coal Mines by Angela V John.