The Christmas Pantomime is a peculiarly British tradition. Although they are occasionally seen in former British colonies, and are often performed abroad by nostalgic ex-pats, other nationalities are rarely amused by girls playing boys, men playing old women and talking animals, in a story loosely based on a nursery tale but with topical jokes, slapstick routines, comic songs and as spectacular a staging as can be afforded.

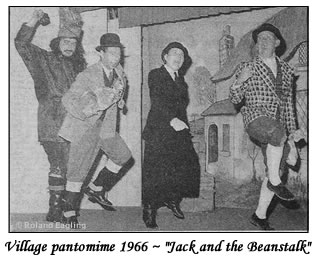

Occasionally an original script is used but the stories of Cinderella, Aladdin, Sleeping Beauty, Dick Whittington, Babes in the Wood, Red Riding Hood, Jack and the Beanstalk, began to be used in the early nineteenth century and are still the ones that are chosen most often. Sometimes a director will decide to try another story line, even have one specially written, but these are rarely as popular as the old stories. Peter Pan, The Wind in the Willows, The Lion the Witch and the Wardrobe and other well loved children’s stories are seen as children’s plays not as pantomime.

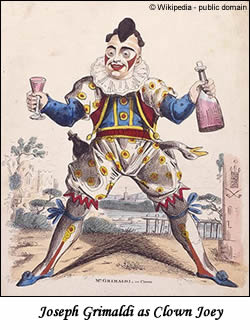

In the past pantomimes were vehicles for actor managers like John Rich and then for particular clowns like Grimaldi or music hall comedians like Dan Leno, first introduced into pantomime by Augustus Harris, who was nicknamed the Father of Modern Pantomime for his elaborate productions at Drury Lane in the 1880s.

It was originally presented for adults but since the nineteenth century has gradually been aimed more towards children. Nowadays professional productions are usually presented by impresarios like Harris who put together companies which tour the country. These professional presentations often employ a TV personality, a popular sportsman or woman, a soap star or a pop singer, to attract the audience. However more often the annual show is presented by the local amateur group in the village hall.

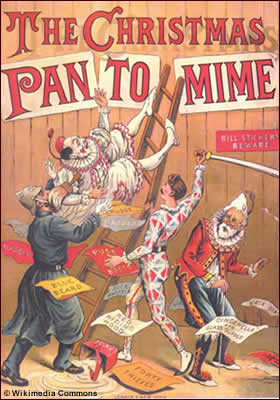

The traditions and stereotypical characters derive from many varied sources. Some can be traced back to the comedies of the Roman dramatists Menander and Plautus and an afterpiece called The Loves of Mars and Venus, an entertainment of dancing in imitation of the ancient Greeks and Romans, presented at Drury Lane by Weaver in 1717, is usually thought of as the first English pantomime. But later pantomimes owed more to the characters of the Italian commedia dell’arte and the harlequinade which developed from that.

In the eighteenth century, John Rich built a repertoire of pantomimes in which, under the stage name of Lun, he used his talent for mime and acrobatic dance as a Harlequin who contrived to overcome adversity by magic. (Slapstick is named for the slap of Harlequin’s magic bat with which he seemed to cause the scenery to change, or rather gave the signal to the stagehands to effect the next change).

The adventures of Harlequin and Columbine formed the basis for chase scenes, acrobatic evasions and magical rescues. Sliding shutters, flying trapezes, stage traps, explosions and smoke enabled sudden appearances and quick scene changes and characters would jump out of the walls, pop up through traps in the floor, or descend to the stage in elaborate chariots.

At first Rich’s Harlequin was masked as in the commedia dell’arte but he soon allowed his mime to take any form. including animal, from which came, for example, an actor playing the cat in Puss in Boots or in Dick Whittington, or the goose in Mother Goose. The cow in Jack and the Beanstalk is usually played by two actors (or actresses) inside a painted skin who probably do a comic dance on the way to market, where it/they are exchanged for the magic beans.

The techniques of the Victorian extravaganza, painted gauzes and special lighting, were added to Rich’s original spectacular settings to manage the transformation scenes and once electricity and hydraulics were available these became even more astounding. A programme for The Sleeping Beauty in The Wood at Covent Garden in 1840 lists twelve scene changes including a Banquet Hall, a Magic Forest and the Illuminated Palace and the Gardens of the Fairy Antidota. It was the transformation scene and the spectacle that drew the audience all through the nineteenth century, although they were not without danger.

In the mid eighteenth century it was reported that “a tumbler…[fell and] beat the breath out of his body, which raised such vociferous applause that lasted longer than the venturesome man’s life, for he never breathed more. Indeed his wife had this comfort: when the truth was known, pity succeeded to the roar of applause”

The stage manager of the Britannia theatre wrote in his diary for 2 January 1865 that a, “Ballet girl burnt tonight…ascending a pillar for the transformation scene, alone, in the absence of the man to assist her up, her under-dress caught fire from the Gas wing lights…she was badly burnt”

Such fires were quite a common occurrence as were accidents with star traps when clowns were caught in them and were badly hurt.

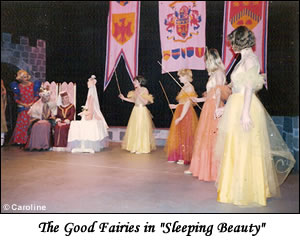

The Victorian taste for melodrama added the moral philosophy of good overcoming evil villainy and made for a proliferation of wicked wizards and fairy godmothers who took over the control of magic from Harlequin. The rather gentle world of the earlier Harlequins where the lovers were simply chased by an angry father through various exploits had changed to a more frightening one where something wicked had to be overcome. Audiences now expected to see the hero and heroine undergo death defying ordeals before virtue triumphed, but they still expected, and expect, to see traditional ‘magical’ special effects and a transformation scene. In Sleeping Beauty the cobweb strewn palace, in which the Princess and her court have slept for one hundred years is transformed by clever lighting and fast scene changing into a brand new one at the instant the prince wakes her with his kiss. In Cinderella the pumpkin and the mice are turned into a full size coach drawn by actual ponies at the wave of a wand. With modern computer controlled technology ‘magical’ effects are easier to arrange but audience’s expectations are higher and the expense of the special effects account for much of the modern outlay.

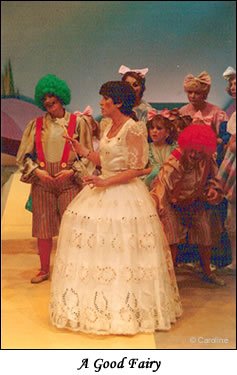

Other expenses include the many changes of gorgeously outrageous costumes, the obligatory chorus of singers and dancers and the accompanying musicians. In the smaller professional or amateur shows these may be less elaborate with the local dance academy or school children acting as the chorus accompanied by a single piano, even so the audience will expect to be affrighted by the wicked characters, charmed by the good, startled and surprised by the magical effects and be invited to shout and sing themselves. For whatever the casting and the special effects much of the success of the actual presentation will depend to a great extent on the ways in which the audience is invited to participate during the performance.

The first true clown in the traditional pantomime was Joseph Grimaldi. He had appeared as a small child in a monkey costume with his father but began his career in 1806 in Harlequin and Mother Goose or The Golden Egg. He was an acrobatic dancer like Rich but where Rich had been a romantic Harlequin always searching for his Columbine, Grimaldi played an anarchic,deliberately mischievous character, who delighted in playing nasty tricks on his friends. This came from the mischief maker element in Harlequin which, combined with the English farceurs tradition, became subsumed into the servant-clown, or the clown buffoon, who related directly to the audience. Grimaldi, and the clowns who followed him, incorporated speciality acts into their performances. One can find echoes from the Harlequinade in the mock fights which turn into a dance, the mimed encounters in the dark, and the acrobatic fooling with a ladder, which were incorporated with tumbling in and out of scene doors and windows, chases with a red-hot poker, fights with strings of sausages or encounters with wallpaper paste. Grimaldi himself became crippled by his acrobatic exertions and on his last appearance in 1828 had to perform sitting on a chair.

Nowadays the clown may take on the role of a mean Baron Hardup or Stoneybroke, or two comedians may play the bumbling Broker’s men who want to foreclose on Jack and his mother or the men who fail to smother the Babes in the Wood. The roles still provide scope for similar comic slapstick routines when played by a well known comedian, but occasionally a retired sports personality a boxer or a footballer, is seen as a draw and then the comedy is usually more in outrageous puns, double entendres and comic routines

Cross-dressing was another of the changes to pantomime during the nineteenth century. At the end of the eighteenth century a vivacious and good looking girl began to be cast as the hero in a breeches part. This derived from the soubrettes from eighteenth century burlesque, who sang sentimental songs and showed off their legs in skin tight trousers. Both Aladdin and Prince Charming would be played by these ‘Principal Boys’ and sometimes there would be a second girl playing Dandini. By the beginning of the twentieth century the girl heroes had become the buxom Principal Boys preferred by the Edwardians. However the Principal Boy is seen less often now that a female’s figure and legs can be seen in ordinary life and today the hero may be played by a male pop star or a good-looking young actor from a popular TV soap. Part of her appeal is that she is often dressed in an extravagant parody of current fashion.

In Cinderella the Fairy Godmother is clearly the force for good and the Ugly Sisters the wicked characters, the latter are still usually both played by actors in role reversal but these are not true Dame figures. Ever since the Greeks, actors have specialised in playing the silly older woman, this broadened under the influence of comedians like Dan Leno in the late nineteenth century into the modern Dame, a transvestite character unique to this form of theatre. Part of her appeal is that she is often dressed in an extravagant parody of current fashion. The Dame was and is more scripted than the clown whose actions were often improvised foolery but she is also the one who now usually instigates the slapstick, and with her advent the prominence of the clown declined. She is a virtuous character, often the foolish but loveable mother of the hero, who relates with the audience by speaking directly to them and inviting them to answer back. (Mother Goose is the only Dame who is not entirely virtuous because she succumbs to greed and sells the goose.) There are links with the traditions of the Music Hall from which Dan Leno had come, when both male and female comics would sometimes cross dress and always play out to the audience. [There is a gallery of pictures of Leno on It’s behind You]

It was said that:-

‘Part of Leno’s amazing success was his gift of taking you into his confidence. The soul of sympathy himself, he made you sympathetic too. He told you his farcical troubles as earnestly as an unquiet soul tells its spiritual ones. You had to share them. His perplexities became yours’

This seems to express the whole relationship between a Dame and her audience but the Dame is not the only character to address the audience. Depending on the story-line virtually any of the characters except (usually) the hero and the heroine may do so. The good fairy as well as the Dame will complicitly include them in their plans. In a modern Sleeping Beauty the Good Fairy, when invited to the christening, says to the audience:-

Goodness ! I haven’t a thing to wear for the Palace. Now that I’m a Fairy Godmother at last, I should have a beautiful shawl. Hm-m .

Spiders, Spiders on the wall,

Weave for me a dainty shawl,

Spin your threads with special care.

Oh yes – and make it wash and wear !

In this case, she is involving the audience both in her feelings of pleasure and in her spell-making, (Spells are usually still cast in rhyming couplets but often the rest of the text is in prose) whereas the wicked witch or the enchanter will set the audience against them, and implicitly invite them to respond with hisses and boos. One of the hidden lessons is the attractiveness of wickedness. For example, on Abanazer‘s first entrance in Aladdin in 1861, he immediately addresses the audience:-

Well, after travelling for many years,

I find myself in Pekin, it appears.

At once, perhaps, I’d make admission,

That I am Abanazer the Magician;

Not a mere conjuror, I’ll have you know,

I keep no caravan, and make no show:

No Houdini, Anderson, Frikel, you see –

>There’s no deception my good friends, in me.

I am the real thing – a HORRID spirit,

A downright British brandy as to merit.

This would be said with the utmost venom too in order to antagonise the audience and a similar technique would be employed today. The wicked witch in Sleeping Beauty is even more objectionable:

To a witch of evil – a Witch of Night,

Right is wrong and wrong is right

I’ll think of some terrible thing

To do to the Princess and do to the King !

For I LIKE to be evil – I LIKE to be mean,

I like to mix the nasty spells that turn my fingers GREEN.

Village Pantomime: SleepingBeauty 1973.

The witch or the wicked fairy or the enchanter deliberately makes the audience privy to their plans so that they become concerned for the innocent, naive Aladdin and his silly washerwoman Dame mother, or worry about Cinderella getting home in time. The audience are therefore deliberately made partisan and subtly inclined towards supporting the good characters.This is a very specialised way of acting which not everyone can manage and keep control but it is a predominate feature of pantomime. It means that the actor must not mind being disliked which can sometimes be a problem for the pop star or TV personality whose popularity is sustained by being loved and admired by their usual audiences.

There is a great deal of encouragement of interjections from the audience, they are often asked to warn of the entrance of particular characters and shout “He/She’s behind you” the next time they appear. Or they are invited to take sides as in Sleeping Beauty and the Beast in 1900 when Beauty’s Tutor holds an arithmetic class to demonstrate the prowess of his pupil but the King and Queen take over. The King says he is a lightning calculator and asks the audience to shout out numbers which the Queen writes on a blackboard. He gives any number as the total and the Queen rapidly cleans off the blackboard before anyone can see that it does not add up. This would be a cue for unscripted repartee. One character will challenge the King saying he has not reached the right total and appeal to the audience to agree. The King will in turn appeal to them to say he did and they will orchestrate choruses of ‘Oh, yes he did’. ‘Oh, no he didn’t.’ Before this can become too unruly another character will initiate the next part of the action and the scripted story will move on.

Every pantomime has an episode of community singing now usually led by the Dame, who conducts patter songs from a song sheet dropped from the flies which will often have topical words set to a well known tune. This tradition seems to have begun with Grimaldi who sang a song called ‘ Hot Codlins’ in which the audience supplied missing (rude) words:-

A little old woman her living she got

By selling codlins, hot, hot, hot;

And this little old woman, who codlins sold,

Tho’ her codlins were hot, she herself felt cold;

So to keep herself warm, she thought it no sin

To fetch for herself a quartern of —[gin] (Oh for shame)

Ri tol iddy,iddy,iddy, iddy,

Ri tol iddy, iddy, ri tol lay.

This little old woman set off in a trot,

To fetch her a quartern of hot! hot! hot!

She swallo’d one glass, and it was so nice,

She tipp’d off another in a trice;

The glass she fill’d till the bottle shrunk,

And this little old women, they say, got —[drunk]

Ri tol etc

This little old woman, while muzzy she got,

Some boys stole her codlins, hot! hot! hot!

Powder under her pan put, and in it round stones;

Says the little old woman, ‘These apples have bones!’

The powder, the pan in her face did send,

Which sent the old woman to her latter—[end]

Ri tol etc.

This little old woman, then up she got,

All in a fury, hot! hot! hot!

Says she, ‘Such boys sure, never were known;

They never will let an old woman alone’.

Now here is a moral, round let it hiss

If you mean to sell codlins, never get—[piss’d]

Rio toll etc.

This was so popular that it continued to be called for after Grimaldi’s death but many other songs were employed including current ones from the music hall and certain actors became associated with particular tunes. Some forty years ago a semi-professional Dame had always sung ‘There’s a Hole in My Bucket, dear Liza’, and would ask one side of the audience to sing the question and the other side to sing the answer. One year he decided they must be bored with it and rehearsed something else instead. However when he began he was shouted down until he gave the audience “The bucket song” in which they joined with gusto.

Most characters will pause for a song, the hero and heroine will perform a sentimental duet, or today sing something from a Lloyd Webber musical if there is money to pay a licence fee. Others will probably add topical words to a well known tune. Usually these songs are satirical and poking fun at some topic of current concern for which Gilbert and Sullivan patter song tunes were found to be ideal once they came out of copyright. There has always been a chorus to give the audience a lead, who sing and dance items like ‘Somewhere over the rainbow’ and give ‘There is no business like show business’ for a grand finale.

A pantomime is often the first introduction to theatre a child has, whether performed by a professional cast in a large city theatre or in the only theatre in a shabby provincial town or by a cast of amateurs in the local village hall. It has become a traditional presentation for the Christmas season, now ostensibly for children but always containing material to attract their elders, for part of the fun nowadays for the adults is in the double entendres and in topical political or satirical references or to local personalities or affairs.

Pantomime continues to evolve and change, adapting itself to the latest taste while still maintaining its original structure, although each generation says “it’s not like it was in my day”. It has even adapted to the World Wide Web on which one can find the nearest performance, read about its history, superstitions and traditions, view pictures of personalities and performances or download a script. Maybe this adaptability is its strength for there are still comedians who specialise in playing the Dame, sometimes girls playing Principal Boys, often an ‘animal’ played by actors, usually spectacular transformations and gorgeous costumes, songs and activities for audience participation, all based on a children’s story such as Cinderella, or Aladdin in which the good characters overcome the bad to end happily ever after.

Marjorie Dawn

© Marjorie Dawn 2008

SOURCES and FURTHER READING

Own copies of pantomime scripts

A Thumbnail History of Commedia Dell’Arte

Google books: Stage Management By Peter Bax