From the early medieval mystery plays through to Shakespeare and the beginnings of modern theatre, plays, and the people who performed them, have held an important place in history and therefore in the lives of our ancestors.

“All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players“

From Humble Beginnings

Medieval streets and village greens acted as the open-air theatre for a variety of performers. Jugglers, acrobats, dancers, jesters and fools roamed the countryside offering entertainment wherever they passed. Ballad singers and taletellers brought their repertoire of old favourites, as well as new songs and gossip from the neighbouring villages. Into this happy mixture came the groups of strolling players, often little better than beggars and vagrants, but they are our first example of professional actors and the beginning of staged performances.

They are our first example of professional actors.The strolling player’s reputation for being a vagrant and ‘n’er-do-well’ was to continue and to become problematic in the late 16th century. In 1572, an act was passed by Parliament declaring that all players with no noble patron to vouch for them would be considered as “rogues, vagabonds and beggars”. The system of being in a noble man’s service was still common. This did not necessarily mean that a retainer was in the paid employment of the nobleman, but it did mean that they could wear his livery and so show that they had a powerful sponsor. Many companies of players begged noble patronage after the passing of this act and, with their licences to present plays safely in hand, they were able to continue touring the country renamed as Lord Leicester’s men, Warwick’s company or other names associated with the powerful landed families of the time. The licence allowed them to perform only plays that had been approved by the wonderfully named ‘Master of Revels’ and forbid them to perform during church services and plague outbreaks.

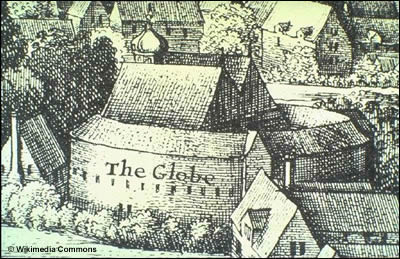

Only one company achieved royal patronage from Queen Elizabeth I, and that was James Burbage’s, the same Burbage who built London’s second purpose built playhouse just outside the City of London, in Shoreditch, in 1576. Before this date Burbage’s troupe of players like other roaming companies had performed in inns and other public spaces, but as they grew in size and became more professional, these makeshift arrangements would no longer do. James designed his playhouse on the same lines as the galleried inn courtyards that they had been used to playing in; oval in shape, with a stage area at the back, a large open area in front of the stage and rows of galleries going up the sides. His ‘Theatre’, as he called it, was a huge success and soon other playhouses began to pop up around London.

After many successful years in Shoreditch the landlord who had leased the land to Burbage started being difficult. Burbage’s response, with the help of his company and a handy carpenter, was to dismantle the theatre, plank by plank, transport it across the Thames to a new site and rebuild it. The theatre reopened soon after as the now very famous Globe Theatre.

The dislike of theatre was rooted in religious disapproval as a more puritanical element was making itself felt in Parliament and in London. The city authorities were very wary of theatres and if the Lord Mayor had had his way they would have been banned completely. He thought that the players were, “ …a very superfluous sort of men”, and restricted performances to Sundays after the evening church service. What he disliked most about plays was the sort of audience they attracted, which he saw as not being much better than the “vagabond” players themselves, and all too prone to rowdiness and lewd behaviour.

As the number of playhouses increased some residents in quieter, more respectable areas put up resistance. Such was the case in Blackfriars when Burbage bought the refectory of the former priory along with the rooms below in order to build another playhouse. The residents objected and Burbage’s company was forbidden from performing there. It eventually opened a few years later, but with children taken from the Chapel Royal choir and local grammar schools. There was already a long tradition of children’s choirs attached to private chapels and wealthy houses.

In fact acting, singing and music were considered essential parts of a young gentleman’s education and institutions such as Oxford and Cambridge and the Inns of Court, allowed their young students and lawyers to write and act in plays. This gave them a respectability and professionalism that the adult companies did not possess and this time the good residents of Blackfriars saw no need to complain.

All the players in these different companies were, of course, men, the stage not being considered a suitable place for ladies. Boys dressed as women played the female roles and, if they had previously been a member of a children’s company, would probably have given a better performance than many of their adult counterparts.

Burbage’s son, Richard, eventually retook possession of the Blackfriars Theatre in 1608. His company, the King’s Men with no less than James I as their patron, used it for their winter performances and the Globe for their summer ones. Burbage shared the ownership of the theatre with six other men, William Shakespeare, Henry Condell, John Heminges, William Sly, Cuthbert Burbage and Thomas Evans. The first four were also actors for the King’s Men and Shakespeare, as we know, wrote plays as well.

Playwrights of the time such as Shakespeare, Ben Johnson and Christopher Marlowe, would probably have been paid for each play they wrote and would have received the proceeds from the first performance. However, once the play had been sold to a company, the writer would have no further input and would earn nothing from subsequent performances. Perhaps it was for this reason that Shakespeare only wrote plays for his own company from 1594 onwards.

The open to the elements Globe type theatres had an impressive capacity of two to three thousand people. Performances were held during daylight hours in the afternoon and there would be an almighty scrum to get to the best places. The plays performed could change from one day to the next. Long runs of the same play as we are used to now were unheard of. The audience was a lively one as food and drink could be purchased and consumed during the performances. Some lucky spectators for a small consideration could even find themselves eating their meat pie in the choice position of a seat on the stage itself, which must have been more than a little disconcerting for the actors! The indoor playhouses such as the Blackfriars Theatre had a smaller capacity but, by using artificial lighting in the form of candles, were able to hold performances into the evening.

Almost as important to an actor as his ability to act (and to turn a deaf ear to less than complimentary remarks from onstage critics) was his wardrobe. Scenery and props played very little role in the productions of the time and so the spectacle came from the gorgeous rich costumes worn by the players – wear a sumptuous doublet and matching bright hose and the audience was putty in your hands.

But all this show and frivolity was not to everyone’s taste. This is what Stephen Gosson (1554-1624), a puritan, had to say on the subject:-

“Plays are the inventions of the devil, the offerings of idolatry, the pomp of wordlings, the blossoms of vanity, the root of apostasy, the food of iniquity, riot and adultery: detest them. Plays are masters of vice, teachers of wantonness, spurs to impurity, the sons of idleness; so long as they live in this order, loathe them”Strong stuff indeed and he was not alone in his abhorrence of all things theatrical. The expansion and progress in theatre at this time was brought to a spectacular halt by the closure of the theatres by Parliament in 1642, with the Globe being destroyed in 1644. Further repressive laws were passed by the Puritans until they finally decreed in 1648, a year before Charles I was beheaded, that all playhouses should be pulled down, all actors seized and whipped and anyone attending plays fined. The theatres were not to reopen for another 18 years and the restoration of Charles II.

After the Restoration

The biggest change when the theatres reopened was the presence of women on the stage. Charles II was fond of ladies and actresses in particular; Nell Gwyn was a longstanding mistress of his and one of the earliest and most successful English actresses.

Samuel Pepys, who was writing his diary at this time, often wrote of the different performances he had seen and the lovely actresses who had taken part. Opinions are divided as to whether the participation of women in the theatre was a form of liberation or just an opportunity for the male audience to appreciate the female form. One thing is certain; it was possible for some actresses to have a remarkable career without attracting the whiff of scandal, Ann Bracegirdle for example, who was presented with 800 guineas by Lord Halifax for her virtue. This is also the time when we see the first woman playwright in the form of Aphra Behn.

The theatre was considered entertainment not only for the gentry and aristocrats but also for the middle classes such as Pepys. He liked the theatre enormously and would sometimes pay a man to keep a seat for him as the theatre doors would open at noon, but the performance would not start for several hours. We know that his wife Elizabeth accompanied him to the theatre and even went on her own with friends, so women were not only acceptable on the stage but also in the audience.

Scenery now played an important role in the productions, with scene changes sometimes taking place in view of the audience. The actresses would fill in the waiting time while the changes took place with songs and dancing. Trap doors were being used to spectacular effect and the productions were becoming more and more elaborate.

Only two theatre companies had been granted Royal Patents by Charles II to perform, the King’s Company run by Thomas Kiligrew, and the Duke’s Company run by William Davenant. Competition between the two was stiff and each tried to outdo the other by staging more and more complex and spectacular shows alongside their more traditional repertoire. The decorating and changing of the scenes meant that theatres now needed to employ not just actors and actresses, but also a growing number of behind the scenes workers and the number of professions associated with the theatre increased.

Theatres needed a Royal patent to be able to perform, this requirement stayed in place until the Theatre Regulations Act of 1843. This was all part of a general feeling that the exuberance and liberty of the theatres was dangerous. Theatre was a potential vehicle for criticising the King and his Parliament and no-one in high office wanted to run the risk of being ridiculed on stage. If the number of legitimate theatres was controlled along with the type of play they were allowed to perform, it was hoped that all would be well. The licensed theatres were required, in 1737, to put on only ‘legitimate theatre’ in the form of comedies and drama and the job of censoring any new material moved from our friend the Master of Revels to the Lord Chamberlain’s office.

All sorts of strategies were cooked up by the theatre companies to enable them to by pass the restrictions and many of them, instead of going underground, simply moved outside, to the pleasure gardens and fairs. The system of Royal London patents effectively meant that no ‘legitimate theatre’ could take place outside of London. Many towns were too small to be able to support a permanent theatre and so they relied on the touring companies that visited with the fairs, but despite the restrictions, by the end of the 1720s three provincial towns, York, Bath and Norwich had their own companies. The legislation was relaxed a little in 1788 with the Enabling Act, which passed the right to confer licences onto local magistrates.

Life as a member of one of the touring companies was a hard one. In 1782 a pregnant Dora Jordan joined Tate Wilkinson’s company on its 150 mile northern circuit. Like most companies, Wilkinson’s timetable was determined by the assizes, fairs and race meetings. They would be in York for the spring assizes, Leeds in June and July, Pontefract in August, York again for the August races, Wakefield and then Doncaster for the September and October ones, finishing in Hull for November and December.

The route would be walked by most of the company, the only transport being horses for some of the better paid actors and the scenery wagon which might offer a lift to the children. Wilkinson’s company numbered about thirty people not including the children. They were actors and actresses but also musicians, scene painters, prompters and their families. Dora and her companions were lucky; Tate Wilkinson was a kindly man with a reputation for looking after his actors and actresses. He had taken Dora on despite her ‘interesting’ state because he could see that she had real talent. Being pregnant was not an obstacle to her performing and Dora acted almost right up to the birth of her daughter in the November.

When the company arrived in a town everyone had to find lodgings. Pay was not good and the itinerant lifestyle of the players meant that few would have been able to afford a permanent home anywhere. The work was demanding as they performed several different plays in each location to ensure a full house at every performance and the actors had to be capable of learning their lines quickly. The theatre would open at four, with the performance starting at six and finishing around midnight. As well as the main play there would also be a farce, songs, dances and recitals.

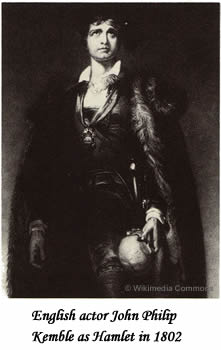

When Dora started working for Wilkinson her wages were 15s a week and a benefit. A benefit was very important to actors and actresses, it was a performance for which they were responsible for the advertising and for which they would receive most of the proceeds. If the play was popular and the audience a large one the proceeds could make up a tidy sum. At the same period John Kemble, who had begun his ascension to real star status but who still had a way to go, was being paid £10 a night as a member of Richard Daly’s company. Dora might have had as many lines to learn as Kemble, but their salaries were not in the same league.

Improvements were continuing to be made in lighting and behind the scenes machinery. On the Yorkshire circuit the stage lighting was supplied by candles at the front of the stage (Dora had a nasty fright one night when she stepped too close to one and her costume caught light), but in London’s theatres lighting came from chandeliers above the stage or, as in the case of Drury Lane under the management of Sheridan, chandeliers hanging in the wings. No-one had as yet thought of lowering the house lights during the performance to increase the visibility of the action on the stage, because, as every self respecting dandy and lady of fashion knew, one went to the theatre to be seen as much as to see.

Visibility must have been a problem, though. The rebuilding of both Drury Lane and Covent Garden during the 18th century meant that they now had a capacity of two to three thousand. The all important metal structures that would enable the theatres to support balconies above the auditorium would not come into being until the second half of the 19th century and so the theatres extended ever outwards, making it doubtful that much of the show could have been seen from the back of the house.

From the Victorian Spectacle

By the time the Theatre Regulations Act arrived in 1843, theatres had opened up all over the place, in the spa towns and in the larger provincial towns, rendering it virtually obsolete. All theatre was now legitimate although prior censorship of plays would continue right up to 1968. Now began the real expansion of the performing arts with theatres offering the traditional drama and comedies to well to do audiences and the pubs, taverns and penny gaffs, providing a mix of songs and burlettas that would eventually form the basis of the music halls, to the working classes.

London expanded and the theatres spread with it. New transport in the form of the railways and the underground meant that the theatres no longer relied on those people who lived near by to watch their plays. Their audiences could travel in from further afield, so theatres could start performing the same production for a consecutive run of nights. If a production was successful in London the theatre manager might put together a special cast to take it round the country, performing in the provincial theatres and thus bringing London standards to the rest of the country.

At the same time the touring companies continued to travel their circuits and perform their repertoire to contented audiences. Unfortunately, the 20th century was not to be as kind to them as the previous ones had been. The arrival of cinema and the First World War dealt them a hard blow and precipitated their decline. Just before the outbreak of war there were 170 touring companies, twenty years later, in the 30s, their number stood at just 37.

By the end of the 19th century, theatre began to be taken more seriously; it was no longer just considered as an opportunity to be seen and to do some socialising. Towards the end of the century the lights were dimmed in the auditorium at crucial moments during the play. However, in the theatres where the plays involved singing and the management were hoping to gain extra money from the sale of the accompanying song sheets, the lights were left up to enable the audience to follow the words on the paper as well as the action on the stage.

Plays and their actors and actresses were now becoming part of everyday life. Magazines could be bought showing fashion plates of the costumes worn on the stage and patterns began to be produced meaning that every fashion lover could wear their own bit of theatrical splendour. Costume makers began to be listed in the programmes and the large shops were happy to see their stock used as furniture or props in big productions confident that it was good advertising for them. In short, theatre, and in particular the theatres in the West End of London were now all about making money.

Late Victorian and Early Edwardian stars of the London stage were the celebrities of the time. Many were very rich and following a tradition laid down by their Elizabethan counterparts they would often go on to become theatre managers themselves.

Elizabethan London and Restoration London ~ Liza Picard

Into this star-studded commercial world came the repertory movement at the beginning of the 20th century, exemplified by Annie Horniman in Manchester: A Thoroughly Modern Woman.

Consuming Passions ~ Judith Flanders

The idea was to assemble a dedicated and stable company of actors and actresses interested more in the quality and scope of their productions than in financial profit. The repertory companies based in the provincial towns aimed to offer a range of plays both modern and old, familiar and challenging to the local population. The plays would run for a couple of weeks before being replaced by another production. The idea was to offer quality theatre to the largest proportion of the population as possible. The people involved in the repertory movement were beginning to see the educational possibilities of theatre; they believed that culture was for everyone and did their best to achieve this.

Consuming Passions ~ Judith Flanders

Their task was made easier after the Second World War when in 1946 the Arts Council was founded and subsidies became available for local theatres. The repertory companies could now afford to do slightly longer runs of their productions, to experiment with new types of theatre and to encourage new talent. The period after the Second World War also saw a move by playwrights to more gritty subjects and, when theatre censorship was finally abolished in 1968, plays were at last able to deal with all subjects, even the most taboo.

Georgette

© Georgette 2008

Mrs Jordan’s Profession ~ Claire Tomalin

Sources and Further Reading

Consuming Passions ~ Judith Flanders

The Repertory Movement: A History Of Regional Theatre in Britain ~ George RowellThe English Stage ~ J.L. Styan

V&A Theatre and performance

Elizabethan TheatreThe Stage Archive

Royal Opera House Collections Online

Consuming Passions ~ Judith Flanders

The Repertory Movement: A History Of Regional Theatre in Britain ~ George RowellThe English Stage ~ J.L. Styan