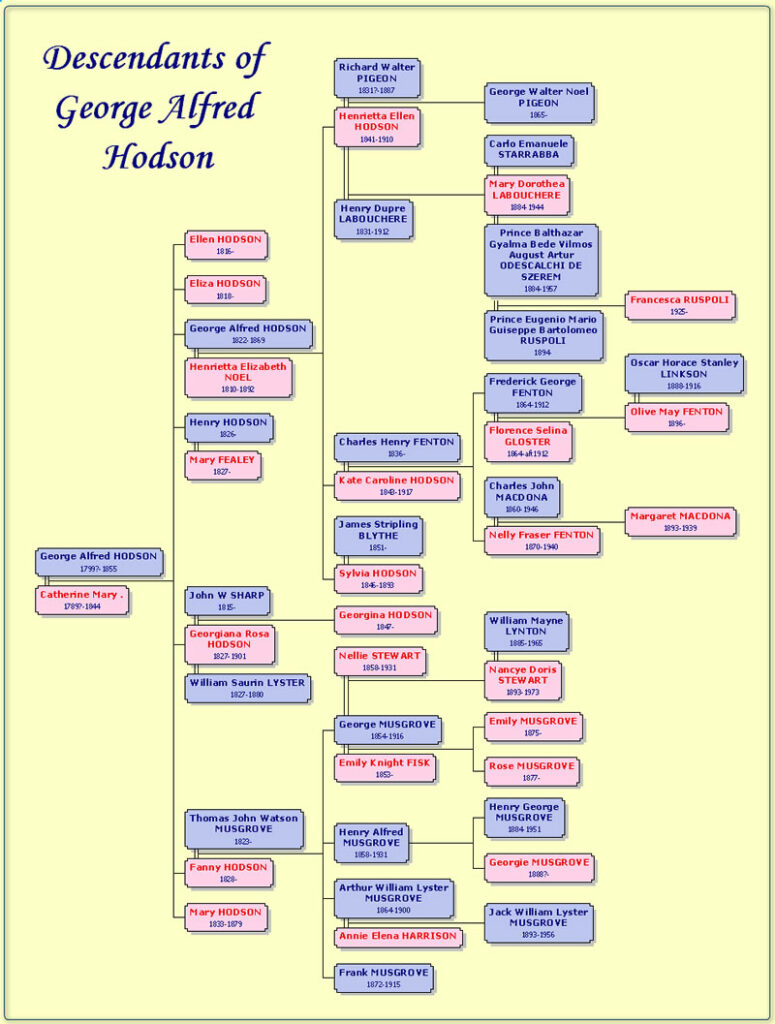

My great x5 grandfather, George Alfred Hodson, was born at the end of the 18th century in Dublin. He became a teacher of music but also composed songs for operas and music halls, as well as singing and acting. George married quite young to an actress called Catherine Maria, who, according to many biographies of their descendants, was a relative of Sarah Siddons and the Kembles, the greatest acting family of the era.

George and Catherine had seven children between 1816 and 1833, and all but one entered the theatre in one form or another starting a theatrical dynasty that would pass on through several generations of the family as they dispersed around the world.

My first trace of George appeared in The Times newspaper on 8th September 1818, which reported on a row between George, his wife Catherine and Frederick Jones, the manager of the Crow Street Theatre in Dublin. The brief article told how George had written to the public to apologise for not appearing as advertised, but following an insult to Mrs Hodson from Jones he awaited an apology before working for him again. What exactly the insult was the paper chose not to reveal, but I felt incredibly proud of George for putting his career on the line to protect the honour of his wife.

A few years later on a trip to Ireland, I looked the event up in the local Dublin paper ‘Carrick’s Morning Post’, to see if there had been any resolution to the disagreement. It turned out that the full row had been conducted very publicly in a series of letters sent to the offices of the Morning Post and reproduced in full. The Hodsons accused Jones of verbally insulting Catherine one day during rehearsals, and therefore refused to perform. George also withdrew all rights to the performance of his songs. Jones in turn argued the row was actually over their contract to play a season in Cork later that year and it was George who had insulted him. The Hodsons were entering into a very dangerous game, for at that time Dublin only had a handful of theatres, Crow Street and Fishamble Street (both managed by Jones) and the New Theatre Royal. If they failed to resolve their row with Jones the likelihood of them obtaining acting and singing parts in their home town would be limited.

The withdrawal of permission to use George’s song ‘Haste Idle Time’ from the opera at Crow Street also made headlines after it’s omission led to riots amongst the audience, with the Morning Post reporting on 8th September:

“The tumult now became serious; apples and other missiles were thrown on the stage. Miss Kelly, we regret to say, was hit in the mouth… A person in the pit was taken into custody by the police, who had been sent for, but we believe he escaped from them”.

The letters to the newspaper end after a week, and the Hodsons are advertised in the production of ‘Artaxerxes’ at Crow Street the following week, so it appears that the dispute was resolved amicably.

Just over a decade later, in 1831, the Hodsons moved to London. By now they had six children; Ellen, Eliza, my great x4 grandfather George Alfred junior, Henry, Georgiana Rosa, Fanny and Mary. George advertised in ‘The Era’ newspaper for his newly formed Musical Academy in Fitzroy Sqaure, Belgravia, for the “Nobility and Gentry of London”, a thriving business he had started successfully in Dublin a few years earlier. He continued to compose songs for the musical halls and penny gaffs, which were springing up all over London, and before long his experience and talent took him back to the stage, when in 1837 he took on the management of the newly built Royal Apollo Saloon, a music hall at the Yorkshire Stingo tea gardens in Paddington.

It was said that, “The programme comprised of an ambitious operatic or dramatic performance, a farce, and a liberal amount of singing and dancing, in all of which each member of the company was expected to take part”

By 1841 he had made sufficient money from selling his songs to buy his own small theatre, The Bower Saloon in Lambeth, which at the time was a rough establishment attached to the Duke’s Head Tavern. George turned the theatre around and utilised his children in his nightly productions. Ellen was an opera singer, George junior a singer and comedian, Henry an actor, and Georgiana, Fanny and Mary, actresses and singers. It was by no means a classy venue and fell into the category of a ‘penny gaff’, frequented mostly by the working class of London, many of whom would walk miles across the city for a glimpse of the burlesques and the chance to heckle the amateurs allowed to try out their talents on the public.

Throughout the early 1840s George’s popularity (or, that of his songs) meant that he continued to tour Great Britain giving small runs of his shows, so much of the running of the Bower was left to Catherine. On Christmas Eve 1844 she had gone with George to arrange the printing of the play bills for the following week and on returning home in the evening complained of sickness and feeling unwell. On Christmas morning they sent for the surgeon after she was unable to get into her bed and was shivering uncontrollably. Her daughter Ellen visited her just after 2 o’ clock and found her sleeping, but on returning a short while later, she had died. The inquest into her sudden death was held the following week on the stage at the Bower, with her cause of death recorded as “Natural death caused by rupture of the brain”.

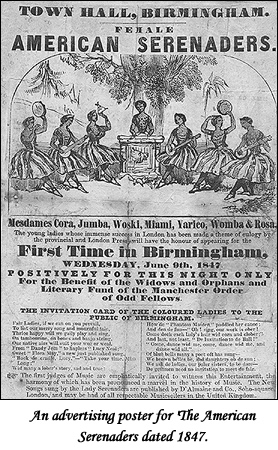

In 1846 George sold the Bower to take his newest venture ‘The Female American Serenaders’ on a tour of Britain. Whilst groups of ‘blackfaced minstrels’ of the time were usually white and male, who blacked up to mimic plantation songs, George’s troupe were all women.

The Birmingham Journal wrote in 1847:-

“The band of Ethiopian Serenaders consists of seven females, their faces coloured to a complexion resembling that of the Bushmen, wearing short petticoats which allows a full view of legs encased in reddish brown skin tights; on various parts of their bodies there is an abundance of brass, and, as may be supposed, that material is not wanting in other respects.”

In the following years he continued with the serenaders, his songwriting and other more questionable ventures (amongst them a troupe of performing poodles). He eventually returned and settled in London where he died in 1855. He left a catalogue of over sixty songs which continued to be played in the musical halls and theatres for decades after his death, but by far his greatest legacy was to be his family

Although George had ample opportunity to promote the many talents of his children in his own theatres, all of them were sent away from home to learn their trade. As teenagers they were sent into the provinces to be trained, some travelling as far as Glasgow and Edinburgh. George Alfred Hodson junior went to Bath, at the age of 17, where he honed his talent for Irish comic impersonations and singing.

Whilst there he met and fell in love with Henrietta Noel, another aspiring actress who was 12 years his senior. They married in 1840 before returning to London to take up roles, he at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, and she at the Bower. On 26th March 1841, shortly after her performance had ended and the crowd dispersed, Henrietta gave birth to her first daughter, Henrietta Ellen Hodson, amongst the sawdust of the orchestra pit at the Bower. She was back on stage the next night. Two more daughters were to complete George junior’s family, my great x3 grandmother Kate Caroline in 1844 and Sylvia in 1846.

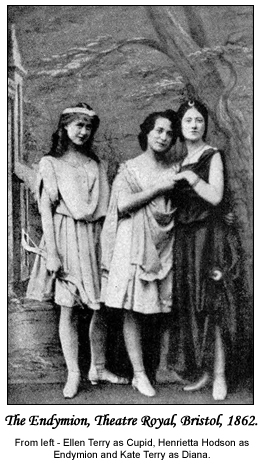

All three girls eventually took to the stage with varying success. Henrietta made her first performance in Glasgow, aged 17. She honed her skills, and in 1860 met Henry Irving (who was later to be knighted for his services to the theatre) at Greenock. The two became great friends and travelled together to Manchester and took employment at the Theatre Royal. In 1861 she was working in Bath and Bristol alongside Kate and Ellen Terry (later Dame Ellen Terry), who wrote in her biography:-

“Miss Hodson was a brilliant burlesque actress, a good singer, and a capital dancer. She had great personal charm, too, and was an enormous favourite with the Bristol public. I cannot exactly call her a ‘rival’ of my sister Kate, for Kate was the ‘principal lady’ or ‘star’, and Henrietta Hodson the ‘soubrette’, and, in burlesque, the ‘principal boy’.

Nevertheless, there were certainly rival factions of admirers, and the friendly antagonism between the Hodsonites and the Terryites used to amuse us all greatly. We all had scores of admirers, but their youthful ardor seemed to be satisfied by tracking us when we went to rehearsal in the morning and waiting for us outside the stage door at night”

One admirer of Henrietta’s was a lawyer called Richard Pigeon whom she married in 1864. He insisted that she leave the stage and by 1865 she had settled with him and their son George in Bristol. Her happiness was short-lived as Richard turned out to be a violent drunk, so she fled back to London. With no support from her husband and little chance of a divorce she took once more to the stage.

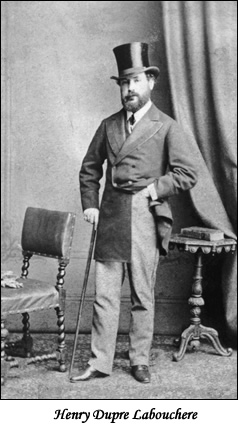

Her beauty and talent soon gained her another admirer. Henry Dupre Labouchere was the owner of a satirical newspaper, ‘The Truth’, an MP and a vastly wealthy man. To win Henrietta’s affection he purchased the Queen’s Theatre in Covent Garden for her in 1867, and by the following year the two were openly living together which caused much scandal in Victorian high society, as her husband remained very much alive in Bristol.

Henrietta retired from the stage in 1879 following the financial collapse of the Queen’s Theatre, and settled herself into life as ‘Mrs Labouchere’, entertaining dignitaries at their house in Queen Anne’s Gate. Henrietta formed great friendships with her contemporaries, including Oscar Wilde (who nicknamed her Little Hettie), James Whistler and William Gilbert (of Gilbert & Sullivan fame), although her falling out with Gilbert was, like her grandparents before her in 1818, carried out in the pages of the newspapers.

On the 1881 census, Henrietta showed her disdain for the way her relationship with Henry was viewed by filling in her occupation as ‘Concubine’. That same year, Henrietta was introduced by Oscar Wilde to the infamous Lillie Langtry. She tutored Lillie in the gardens of Pope’s Villa, her home in Twickenham, for the role of Kate Hardcastle in ‘She Stoops to Conquer’, and it was there that Lillie made her first performance at one of the Labouchere’s many parties.

The following Autumn, Lillie made her debut in America and Henrietta accompanied her as a chaperone, along with her sister Kate. Now a well established actress, it was hoped Kate’s presence would enhance the still slightly amateurish performance of Lillie. Pursued by admirers across the country, Lillie had a major falling out with Henrietta over her entertaining of one unsuitable gentleman, and Henrietta returned home before the tour had ended, the two no longer able to work together.

The Laboucheres had a daughter, Mary Dorothea, who was born in Paris in 1884, and finally, in 1887, they were able to marry following the death of Richard Pigeon, who was by then an unemployed drunkard. Henry continued to work tirelessly as an MP and Henrietta made occasional appearances in benefit productions throughout London. She continued to throw lavish parties at Pope’s Villa, including one in 1887 for the entire cast of Buffalo Bill’s Circus who stripped the bushes of all the berries, and went home having stuffed their bags with grapes, biscuits, cigarettes and cake.

They focussed their attentions on giving their daughter an upbringing that would enable her to marry the ‘right sort of gentleman’, which paid off when in 1903 she married the son of the Italian Prime Minister, followed by two further marriages to Prince Balthazar of Odescalchi in 1915 and Prince Eugenio di Ruspoli in 1927.

The Laboucheres retired to a villa in Florence, Italy, where Henrietta died in 1910, with Henry dying just 15 months later, having never recovered from losing the love of his life.

Although Henrietta was by far the most prominent and successful of George’s descendants, she was not the only artist. Her sister Kate became an actress and had great success in the UK and America. Kate’s daughter, Nelly, followed her into the profession and married Charles Macdona, a theatre producer who was responsible for debuting the works of George Bernard Shaw on the stage. Their daughter Margaret Macdona was also an actress.

Two of George and Catherine’s daughters, Georgiana and Fanny, moved to Australia. Georgiana Hodson went first to America, where in 1857 she joined an operatic company managed by Frederick and William Lyster. They toured across America before embarking on a short trip to Melbourne in 1861. Having played to great success the company eventually made their base in Melbourne, from where they toured the colonies presenting the first professional operas they had ever seen such as ‘Il Trovatore’, ‘Lucrezia Borgia’, ‘La Traviata’, and ‘Faust’.

Georgiana and William Lyster married in 1868, their romance having developed as Georgiana worked so closely with William as his ‘prima donna’. In the following years Lyster introduced Australia to Offenbach and Wagner, whilst dominating the country’s operatic scene. In 1865 he spent his hard earned money buying up 1200 acres of land in Narree Warren, a decade later he donated some back to the locals to build a school which they called ‘Lysterfield’ in his honour.

After Lyster’s death in 1880, the production of grand operas fell into decline, and it was not until the 1960s that such quality returned to Australian operatics.

Fanny emigrated to Australia in 1863 with her husband Thomas Musgrove, taking with them their eight children. The youngest child contracted an illness on the voyage and died within weeks of arriving, although they were to have another five children in their new homeland. Her son, George Musgrove, was taken by Lyster to one of his theatres as a child and became enamoured by the ‘magic’ which happened there.

Upon leaving school he took a job as a clerk in Lyster’s office where he started to learn his uncle’s trade. He produced his first opera in Melbourne in 1880, before forming a partnership with JC Williamson and Arthur Garner, the three of them taking control of Melbourne and Sydney’s theatres. He married and had two daughters, Emily and Rose (another actress), although he had a very public affair with one of Australia’s most popular actresses, Nellie Stewart, whom he had employed in 1892. She fell pregnant and the two fled to England under the guise of a season on the London stage. She gave birth to a daughter, Nancye Stewart, in Essex, in 1893.

George and Nellie’s relationship remained strong, with her later describing him in her autobiography as the ‘greatest love of her life’, and they lived together in Sydney until George’s death in 1916. Their daughter Nancye also became an actress, and married William Mayne Lynton, with the two becoming pioneers of radio drama, performing in more than 500 radio plays.

The Musgrove family continued to be key figures in Austrailan theatre after the death of George. His brother Henry Alfred Musgrove had become a cricketer and played one test match for the Australian team before going on to become the team manager. He later took up employment in the theatre as a manager for his uncle, William Lyster. His daughter, Georgie Musgrove, also became an actress.

George’s brother, Arthur, had two sons Jack and Harry who were partners in one of Australia’s first film production and distribution companies, thus continuing the dramatic dynasty.

samesizedfeet

© samesizedfeet 2008

SOURCES

The Early Doors, Origins of the Music Hall by Harold Scott

The Variety Stage: A History of the Music Halls from the Earliest Period by Charles Douglas Stuart, A. J. Park

Opera in Dublin 1798-1820: Frederick Jones and the Crow Street Theatre by T. J. Walsh

The Science of Music in Britain, 1714-1830 by Jamie Croy Kassler

The Stage Door: Stories by Those who Enter it by Clement William Scott

The Golden Age of Australian Opera: W.S.Lyster and his Companies 1861-1880 by Harold Love

Labby: the Life of Henry Labouchere by Hesketh Pearson

The Life of Henry Labouchere by Algar Labouchere Thorold