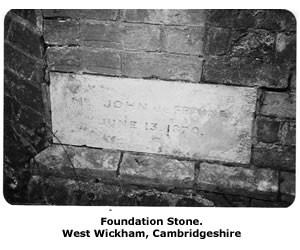

Some thirty years ago while house-hunting we went to see what the agent said was a small chapel ‘ripe for conversion’ in the village of West Wickham in Cambridgeshire. The chapel was tiny and needed far too much done to it for us to afford to make it habitable but then we suddenly saw a foundation stone behind the nettles and a different search began.

A Mrs John de Fraine had laid the stone on the 13th June 1870. This was my fairly unusual family name but we are a Buckinghamshire family and as I knew of no relatives in the area, this was intriguing.

In the churchyard we found several de Fraine graves which gave me some dates and names to research including John himself who died in 1910, and the hunt was on.

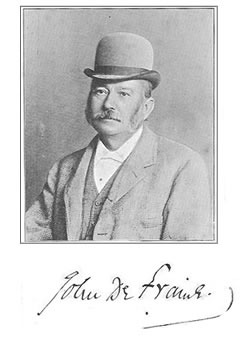

I found that John de Fraine had been a well known lecturer in the nineteenth century who had travelled the country talking to large audiences on leading a good Christian life and avoiding the demon drink

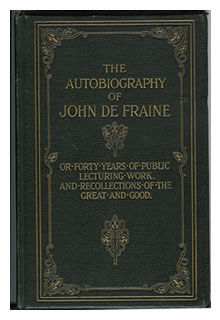

I was lucky enough to find a copy of his autobiography which gives the impression of someone totally self absorbed with his own affairs and with little time for anything outside what he saw as his mission in life. The autobiography says little about his family life but lists the many places he visited, quoting extracts from the complimentary remarks when people praised him and noting when he met people of consequence like Dickens and Thackeray, and those in the temperance movement like the artist George Cruikshank, whose painting The Worship of Bacchus with its depiction of all kinds of drunken behaviour John saw at the private view in 1869. (It was on view at Tate Britain in 2001 after restoration.) There is a picture of it on the Tate Britain web page.

For his was very much a public life. He tells how he became a lecturer for temperance and the Band of Hope when a very young man after living with a drunken father as a child. He describes his father, Joseph, fighting imaginary ghosts and demons in the throes of delirium tremens, and of seeing his mother’s face all bloody from his father’s blows. However, when he was eleven his father joined the temperance society and took the pledge and John’s life was much happier after that. He speaks of Joseph as a kind and witty man but he never forgot the suffering the drink caused his mother.

He was born in Aylesbury in 1838 and belonged to a large family of de Fraines in and around the town but he does not mention any of these relations, and writes as if he was an only child yet the census shows he was the youngest of four, and perhaps therefore the closest to his mother whom he clearly adored. He was distraught when she died when he was twenty and, from the reports on his lectures, would use her life as an example of pure goodness under the immense hardship of the cruelty and poverty caused by her husband’s drunken behaviour.

He speaks feelingly of his wife, wrote a touching poem for their Silver Wedding, with a religious sentiment, and says how much he missed her companionship when she died, after thirty seven years. Yet he mentions none of his children by name and only once notes when they were born, and that because the birth occurred after a tragic accident. In 1870 there was fire in the house and he makes much of the death of the dog who warned them, even writing to The Times about it, only adding almost as an afterthought in the autobiography that his wife presented him with a Valentine gift of a daughter next day. This would have been his second child, Frances Mary Elizabeth. He says his eldest son, when seven years old, laid the foundation stone for the Reading room he added to the Mission Hall in 1875, but he does not name him. The 1871 census shows the son was called John too.

Three daughters are buried in the churchyard; Frances Mary Elizabeth born after the fire died in 1943, Ursula Maud born in 1871 died in 1946 and Marie or possibly Annie Maria who was born in 1874 and died in 1950. The three daughters are thought to have left the village when their father died but it is uncertain where they settled. It may have been one of them who was advertising from Cambridge to be a nursery governess to teach ‘first lessons, music, elementary French, needlework’ in The Times in the 1920s but that has yet to be proved. They may not have been particularly well educated for John clearly saw woman’s role as supporting her man so he can avoid the temptations of alcohol. In his lectures he often inveighs against servant girls who spend their money on fripperies and dress more finely than their station and in one asks:-

And now, can any of you tell of what use it is to teach a poor girl, who is to become the wife of a hard working labouring man, the height of a mountain, or the length of a river, or to have known fifteen fine names for a pudding bag when she knows positively nothing of that which is to fit her to be one of the lights of an English homes, and one of the mother’s of people brave and free. There’s plenty of ‘ism’ and ‘ology’ – but not enough scrubology, and sewology, and bakeology and boilology, and pudding-makeology, and the ology that would do something towards making a poor man’s fireside a more attractive spot, than the sanded taproom and the bright parlour of the Blue Badger and the Green Pig.

Although one must remember that he is always aiming his words at the labouring poor. There was another son, Thomas born in 1876, who was the parish clerk at West Wickham until 1908 while his father was Chairman of the Parish Council. Nothing is known of him after that and it is rumoured that he may have been an alcoholic which would have been extraordinarily sad.

John himself was very well educated for the time, not leaving school until almost fifteen and even then was encouraged by his local clergyman to continue reading. His delight was in attending lectures and public meetings, where he listened to speakers such as Livingstone, Disraeli and Samuel Wilberforce, whom he says gave him a taste for speaking in public himself. He started when his father put him on the table in a public house to recite a poem and from seventeen to twenty spoke at many local meetings in the towns nearby, often in the open air. An early report of one of these meetings was not very flattering. Jackson’s Oxford Journal reports flatly that in Buckingham on 11th June 1857:

Mr John de Fraine delivered a lecture on “Total Abstinence” in this Market Place. There were not many people there and the affair was dull and spiritless.

But he was only nineteen. The experience did not put him off and he continued to travel round the district addressing open air meetings, which must have taken some courage but would have trained him in the techniques necessary to use both his voice and his subject matter to hold an audience.

After his mother’s death he was invited to go to London by the National Temperance League as their clerk and from there he soon started on his career as a lecturer on total abstinence from alcohol, receiving his first professional fee at Leamington Spa in November 1858 when he was just twenty. He was told years later than a man who had heard him at that first meeting was so impressed he named his new house De Fraine Cottage.

The British Association for the Promotion of Temperance had been formed by working men in Preston in 1832. At first the members only abstained from spirits but soon the society was pressing for total abstinence. The Band of Hope for working class children was formed in Leeds in 1847 and organisations such as the Salvation Army and the Quakers became actively involved in campaigning with non-conformists, Baptists and congregational ministers.

While never ordained John must have been popular with these various groups for the ministers would invite him to stay in their houses and ask him to return to address their congregations many times. The meetings usually started with a hymn and a prayer and were often chaired by a clergyman. At Kenilworth the Band of Hope greeted him with a song composed specially for him

Welcome to John de Fraine,

We’re glad he’s come again,

Long live de Fraine

May Heaven’s best gifts descend,

On our twice welcome friend,

On God his hopes depend

God bless de Fraine

Newspaper accounts were soon lauding his oratory in meetings as far away as Jersey and Belfast. In 1861 he spent a month touring and speaking in Ireland where The Belfast Newsletter spoke of “this youthful orator of two and twenty years who spoke on The Battle of Life.” The reporter wrote that he related several well told anecdotes and incidents illustrative of his subject, and, in most thrilling eloquence, repeated several pieces of poetry upon the point of his subject under consideration, of which no idea can be conveyed in a mere outline of his oration, and concluded by urging upon young men to fight the battle of life, having trust in truth and faith in God, and after a most eloquent appeal upon this head he resumed his seat amidst prolonged applause.

It seems that at first much of his appeal lay in his youth. The Newcastle Daily Chronicle said he “appeals as a young man to young men with great earnestness , and we are certain that if the lecture he delivered on Friday night be a fair example of his budget, all who listen to him will be the better for his teaching.”

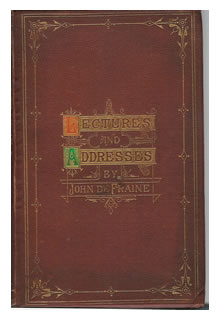

This kind of complimentary remark is repeated in the many reports of his speeches as the years go by. He published several books of his lectures and addresses and they show that, although he was always giving the same message that one should lead a moral life and that it is easier to do so if one avoided alcohol. He larded his remarks with humour, told stories and illustrated his points with quotations or used poems from writers like Tennyson or the American Longfellow as metaphors. This stirring extract is from one of his best known lectures The Battle of Life.

Onward – upward –higher! Excelsior! Up the mountain of knowledge and culture, be the height ever so dazzling, and the summit ever so distant; Excelsior! though the road be rough and rugged, and the stones be sharp under the toiler’s feet; Excelsior! with high resolve and proudly beating heart, for ever listening to that music from afar which beckons forth the better hope; Excelsior ! Step by step, with a spirit to conquer or be conquered, breaking the huge stones of difficulty till from powdered dust you can pick up the gems of precious worth; Excelsior!! for health and strength, and just as travellers climb some Alpine steep to revel in the joy which lies in fertile vales, and ever widening plain; Excelsior!

In life’s rosy morning,

In manhood’s fair pride

Let this be your motto

To comfort and guide;

In cloud and in sunshine

Whatever assail

We’ll onward and conquer,

And never say Fail.

As well as providing his audiences with a varied and wide ranging hour’s talk he must have had a pleasant, clear and attractive speaking voice at a time when there was no amplification. It is difficult for us with all our different kinds of amusement to appreciate how much the Victorians liked a good talking to, but his halls were usually full and often packed out. Nevertheless it entailed an enormous amount of travel sometimes in atrocious conditions. For example, in 1874 he left home for three months speaking in the Midlands, the North and the Scottish Highlands. He writes of twelve hour train journeys, of trudging through snow, of walking twelve miles to reach his hosts after hours on a train. It must have been financially worthwhile for he seems to have earned enough from his appearances to keep his family in some style, bring up five children, and raise the money for the building of the Mission Hall and its Reading room.

The Mission Hall was opened a year after the foundation stones were laid. There had been a fete and free teas for the children with the band of the 17th Essex Rifle Volunteers for that occasion.

At the actual opening on Easter Monday of 1871, of the 45 by 21 foot hall, there was a hymn followed by a prayer by the vicar and John gave an address, after which there were free teas for all the poor of the village, the Haverhill Choral Society sang and “Mr and Mrs Gurteen presided at the piano and harmonium.”

In his address John explains that he had built the hall for the young agricultural labourers where they could have lectures, readings, music “and such other things as I hope will, in the language of the circular that invited you here, promote what Tennyson beautifully calls ‘the common love of good; will rouse the sinful from their sleep of death, and win the vacant and the vain to a heavenlier and better life.”He hoped the hall would continue to “be a light to the whole neighbourhood” and that after his death his children would continue its work “for the moral, and social, and religious elevation of a people yet unborn.”

In 1906 The Newmarket Journal reports that John had allowed use of the hall for a variety entertainment in aid of the West Wickham cricket club which included comic songs and sketches and at which his daughters played the piano and his son Thomas played a gramophone. However after his death the hall was sold as part of his estate. It became a Methodist Chapel but was eventually sold to a builder and became a private house.

In some ways John seems to have acted as the squire of West Wickham. He writes of visiting the poor of the village, and provided them with Christmas goods and free teas on special occasions. There is something admirable about his benevolence but it is perhaps tinged with a slight sense of self-righteousness.

In 1888 he stood for the first Cambridgeshire County Council, and served for one term but would not stand again. Saying he “did not think the work was congenial to me” and that he could not afford the time or the means to continue. It was probably hard for him to work as a committee man having been his own master all his life. He continued to travel the country to lecture and wrote several short books all based on his addresses. He remarks that some years earlier he had begun to give his lectures for free trusting in the collections to defray his expenses. He did draw the crowds, and remarks on their generosity but there was little left over once all the travelling and other expenses were cleared and he says he will never make his fortune. He finishes his autobiography by explaining why his lecturing was so important to him.

My earnest desire is to promote the Glory of God, extend the Redeemer’s Kingdom, advance the great cause of Temperance, and raise the moral and intellectual tone of the people [….] My earnest desire is to draw lessons from noble life, and historic fact, and deathless deed, and poets song, and show how grand a thing it is for all of us to do our duty and know how sublime a thing it is to suffer and be strong. My earnest desire is to cheer the toiler, and encourage the timid, and strengthen the weak and battle with evil, and throw a ray of heavenly light down the cold and starless road of doubt and despair. In this desire I have lived, God grant that in it I may die.

He lived another ten years. Dying at his long time home in West Wickham in 1910 where he was buried alongside his wife Ursula. He appears to have had one grandchild, although this has to be confirmed, another John who was always known by his second name of George. George worked at the Cambridge University Library for forty four years occasionally appearing in print with an anthology of hymns and with comments on various musical topics. He died in 1965.

And yes, John was a very distant relative, my great grandfather’s second cousin.

Marjorie Dawn

© Marjorie Dawn 2008

Sources.

I am indebted to Janet Morris of West Wickham for correcting some assumptions and filling in many gaps.

The Autobiography of John de Fraine or Forty Years of Lecturing Work, and Recollections of the Great and Good 1900

Lectures and Addresses by John de Fraine nd.

The archives of The Times and various local newspapers.