Most of us when we imagine our 18th and 19th century ancestors see them as God-fearing, law abiding, peaceful people, living in a golden age when life was simpler and easier.

Access to newspaper reports, transportation records and census returns with the local prison as place of abode, have shown some of us that the law abiding part was not necessarily true, so can the same be said of the God-fearing?

“Alick was of opinion that church, like other luxuries, was not to be indulged in often by a foreman who had the weather and the ewes on his mind… I feel sure Alick meant no irreverence; indeed, I know…he would on no account have missed going to church on Christmas Day, Easter Sunday, and “Whissuntide.” But he had a general impression that public worship and religious ceremonies, like other non-productive employments, were intended for people who had leisure.”

Adam Bede by George Eliot

The Church of England was the established church and, until the early 19th century, the only church allowed to carry out marriages and burials.

If you wanted to be a Member of Parliament, an officer in the Army or go to university, you had to prove, usually with the help of your baptismal certificate, that you were a member of the established church and in agreement with the Thirty-Nine Articles of Faith that embodied England’s separation from Rome in 1562. Catholic emancipation came about in 1829 and for Dissenters, in 1828, although Parliament had become accustomed to pass an annual ‘Act of Forgiveness’ for a number of years before this date, allowing Dissenters to take their seats. Jews and non-believers did not attain equality before the second half of the 19th century.

Baptism into the Church of England was not necessarily an act of faith then, but a way to ensure that your children could take their full place in society, for example, Benjamin Disraeli, despite being from a Jewish family, was able to join Parliament because he had been baptised into the Church of England at the age of 13 in 1817. In the days before civil registration, your baptismal certificate also proved your existence and was needed for such things as apprenticeship agreements and to prove that you were ‘of the parish’ enabling you to receive parish relief if you fell on hard times.

The turmoil of the Industrial revolution in the 18th century and the enormous progress made in science and technology during the 19th century lead many of our ancestors to question their beliefs and their acceptance of the established church. On Sunday March 30th 1851 a religious census was carried out in England and Wales. It had taken some time to put in place, but with the legal penalties for non-completion removed, the three different coloured forms, black print on blue paper for the Anglican churches, red print on blue paper for non-Anglican places of worship and black print on white paper for the Religious Society of Friends or ‘Quakers’, were handed out the week before, ready for filling in on the Sunday. The results were to prove quite a shock to the Victorians; fewer than 60 percent of the population were churchgoers and of that 60 percent 49 percent were Dissenters, 47 percent were Anglicans and 4 percent Catholics. The report, put together by a young solicitor called Horace Mann, sold like hot cakes.

The census showed up lots of other interesting facts. Dissenters were more common in the towns and in the North of England. There were more Catholics in Lancashire than anywhere else and Church of England parishes were better attended in rural locations where the land was still owned by one owner and where most of the adults were employed in agriculture. These facts reflected the social changes of the 18th and early 19th centuries. The population of the towns was increasing and traditional ways of life with their traditional allegiances were changing.

Dissenters believed in a personal relationship with God, in hard work, a belief in their abilities to make their own way in the world and they often had a strong social conscience. Dissenting chapels in towns were often the centre of their congregations’ lives, providing education in their Sunday schools and recreation in the form of outings. Josiah Wedgwood came from a family of Dissenters; he was the fourth generation of a family of potters, through his hard work and interest in technological advances he perfected the pottery making process and built up a considerable fortune. Alongside his business interests he was also preoccupied by social reform and was a keen supporter of the abolition of slavery.

One of his fellow abolitionists was William Wilberforce. He too came from a business rather than a landed gentry background and he was part of a wave of change that flowed through the church at the beginning of the 19th century. The ideas of John Wesley and his ‘Methodism’ appealed to a growing number of Anglicans who still felt an attachment to the established church and they formed a new evangelical movement within the church. From representing an eighth of the Anglican clergy in 1820 the evangelicals rose to representing nearly one half by the middle of the century. They were the force behind many humanitarian movements, which helped to provide decent living conditions for working people, founded orphanages and worked to change the emphasis of the criminal justice system from punishment to reform.

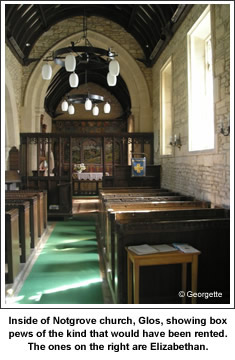

For the urban working and middle classes the dissenting religions and the evangelical branch of the Church of England were attractive. They could be sure to be accepted as equals in a time where the established church appeared to reinforce and uphold the class distinctions of society. Worshippers turning up for church in their working clothes on Sunday would be shown to the free places on hard, bare benches usually at the back of the church whereas, the smartly dressed gentry, would be shown to their curtained and cushioned, enclosed, private pews that they paid for. Pew rents were a significant source of income for the church.

“The pews both of the galleries and the body of the church were provided with soft cushions; for this was a proprietary chapel, and there was but a slender accommodation for the poor. Indeed, this class occupied plain benches in the aisles, and were compelled to enter by a small side-door; so that they might not mingle with the crowd of elegantly dressed ladies and fashionable gentleman that poured into the chapel through the grand entrance in front. A policeman maintained order at the side-door which admitted the humbler classes; but two beadles, wearing huge cocked hats and ample blue cloaks, bedizened with broad gold-lace, and holding gilt wands in their hands, cleared the way for the wealthy, the great, and the proud, who enjoyed the privilege of entrance by means of the front gate.”

The Mysteries of London by GWM Reynolds

In rural areas the local gentry made sure their servants and labourers were present at church on Sunday and some Vicars would distribute their help to needy families depending on whether they were regular churchgoers.

Just as there had been a move towards evangelicalism at the beginning of the 19th century, so the middle of the century brought a move towards high-church practices. The Oxford Movement began in the 1830s with the aim of reinforcing the priest’s authority conferred on him at his ordination by the Bishop and linking him back through time to the apostles. The movement also emphasised the importance of ritual, architecture and vestments. Daily morning and evening services returned to churches for the first time in nearly 300 years, altars became decorated and services more solemn. The founding members were, John Henry Newman, John Keble and Edward Pusey, all three of whom were fellows at Oriel College, Oxford. They wrote a series of tracts for The Times outlining their beliefs and resulting in their alternative name of Tractarians. Tract XC caused uproar when Newman suggested that the thirty-nine articles on which the Church of England was based, were in fact very close to Roman Catholic thinking. It’s perhaps not surprising that Newman converted to Catholicism in 1845 and 446 of his fellow clergymen did the same thing between 1840 and 1899.

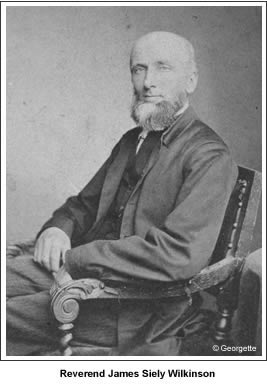

THE CLERGYMEN

“The Doctor was a regular orthodox divine of the eighteenth century; with a large cauliflower wig, shovel-hat, and huge knee-buckles, barely covered by his top-boots; learned, jovial, humorous, and somewhat courtly; truly pious, but not enthusiastic; not forgetful of his tithes, but generous and charitable when they were once paid; never neglecting the sick, yet occasionally following a fox; a fine scholar, an active magistrate, and a good shot; dreading the Pope, and hating the Presbyterians.”

“Venetia” by Benjamin Disraeli

In the 18th and early part of the 19th century, being a clergyman was considered a suitable job for a gentleman. The duties were not too time consuming; a service on Sunday, the occasional baptism or marriage, visiting the sick and collecting the tithes, leaving plenty of time for riding, hunting and other country pursuits.

The parish priest was an important person in the community. He was, as we saw for domestic servants, the first port of call for families keen to find a good ‘place’ for their children, someone who could be relied upon to lend a helping hand when there was sickness in the family and sometimes he was the only person who had received a good education, so his advice was sought after. Clergymen were often appointed as magistrates in the early part of the 19th century. In Oxfordshire in 1816 they made up 36 percent of magistrates, but gradually as the century wore on their numbers decreased as many came to see the two roles as conflicting.

A man had to be at least 23 to become a deacon and prove that he had a nomination to a curacy and 24 to become a priest with a nomination to a curacy or a presentation to a living. He had to prove to the Bishop that he was of sound moral character and, before the 1840s, that he knew his Latin and his Scriptures. There was no formal training, but virtually every candidate would probably have read Classics at either Oxford or Cambridge. Courses in theology were not offered until the 1870s in these two universities and any theological colleges that existed were not always well considered as they brought in professional training to a gentlemanly profession. Residential courses were only introduced after 1910.

Of course, being learned in Latin and scriptures did not necessarily mean that the newly ordained priest would be any good at his job. A wide variety of manuals were available to help out the nervous newcomer, and it was even possible to buy books of sermons should your inspiration run dry. A clergyman could chose the right clothes depending on whether he favoured the High, Low or Broad church from the many ecclesiastical clothing warehouses that advertised in the periodicals of the time.

Getting a nomination to a clerical living was not an easy business and was dependent on having good connections. The right of nominating or presenting a candidate to a living is called an advowson. The advowson is held by a patron, who presents the candidate to the Bishop for induction to the living. The patron may be a person or an institution either secular or clerical. In pride and Prejudice, the odious Mr Collin’s patroness is the equally odious Lady Catherine De Bourgh.

The amount of money that the holder of the living could expect to earn varied. The parish priest and the upkeep of the church were paid for by tithes, which amounted to a tenth of the parish’s yearly product of land and labour. This is where the difference between a rector and a vicar comes in. A rector received all the tithes due to his parish from the product of the arable land, the value of the stock, the labour and the minor produce, but, if the rector was a lay person or an institution rather than a cleric, a vicar would be appointed who would receive the lesser tithes made up of just the labour and the minor produce. In 1868, Doddington in Cambridgeshire, was the richest living, with a yearly income of £7,300 but depending on agricultural values and the size of the parish most livings were worth no where near this amount with the average income put at £246 in 1897.

In 1838 an act was passed in parliament designed to put an end to pluralities, that is, the holding of more than one living by the same person, by placing restrictions on the distance between the parishes and a limit on the joint income to be earned. However, pluralities continued to be a problem, as did non-residence as practised by Dr Vesey Stanhope in Barchester Towers:

“Among the greatest of the diocesan sinners in this respect was Dr. Vesey Stanhope. Years had now passed since he had done a day’s duty, and yet there was no reason against his doing duty except a want of inclination on his own part. He held a prebendal stall in the diocese, one of the best residences in the close, and the two large rectories of Crabtree Canonicorum and Stogpingum. Indeed, he had the cure of three parishes, for that of Eiderdown was joined to Stogpingum. He had resided in Italy for twelve years.”

Parish priests who held several livings or who were non-resident, employed curates to do their duties for them. There were no set wages; it was entirely up to the incumbent how much he paid his curate. Some of them were very badly paid indeed and struggled to make ends meet, although some extra income could be earned in the form of the fees paid for baptisms, weddings and funerals and by taking in young men from the local gentry as pupils.

PARISH ORGANISATION

The rector, vicar or curate was helped in his duties by the parish officers who were elected by the vestry made up of parishioners who paid the church rates. The parish officers included, the churchwarden, the overseers of the poor, the sexton, the verger, the beadle, the constable and the surveyor. These positions were unpaid, but they sometimes came with advantages such as an extra piece of land or payment for a service carried out. Anyone elected to one of these positions was obliged to accept, leading to many busy members of the parish paying to ensure that they were not elected. In small parishes one person could hold two positions.

The parish clerk was also a parish officer, however, he was not elected by the members of the vestry, but was appointed directly by the parish priest.

Not all parish officers were of impeccable character. FTF Administrator Guinevere has a sexton in her tree who was reprimanded in the parish minutes:

From St Margaret’s Vestry minutes 1833: Mr Barrett the sexton was reprimanded for drunkenness and given to understand that if it again occurred he would be dismissed. Fortunately, he soon pulled up his socks. From St Margaret’s Churchwarden’s accounts 1843: John Barrett Sexton paid £9 6s 0d

The Parish Clerk

According to Canon 91(1603) a parish clerk “…should be at least 20 years old. Known to the parson as a man of honest conversation and sufficient for his reading, writing and competent skill in singing”

He would assist during the service by reading the lessons, serving at the altar, leading the responses and the singing. He would make a rough draft of the records of births, deaths and marriages for the vicar to copy into the parish register, which must have hindered accuracy! He collected the fees for the different ceremonies, wrote the banns and generally acted as the vicar’s secretary. His social position meant that he was closer to and more approachable by the parishioners than the vicar and he often acted as an intermediary when they needed help. It was not unusual for the position of parish clerk to be handed down from father to son.

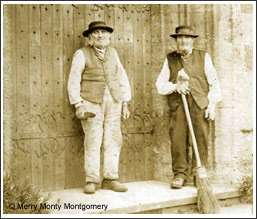

The Sexton

The sexton was the parish clerk’s assistant. He was responsible for the care of the churchyard as well as the inside of the church.

He looked after the vestments and the vessels, rang the bells, opened and closed the church doors and dug the graves.

He would earn a fixed amount for each burial carried out and would ring the ‘passing bell’ announcing the death of a parishioner. In some churches the initial number of tolls indicated whether the dead person was male or female, married or unmarried, adult or child and these tolls where generally followed by a pause and then a chime for each year of the person’s life.

In small parishes the same person might carry out the duties of the parish clerk and the sexton. In larger parishes a verger, who was responsible for the interior of the church, might assist the sexton.

The Churchwarden

The wardens held considerable power and the constable, surveyor and verger reported directly to them. They were responsible for the fabric of the nave; setting and collecting the church rates, collecting and distributing any gifts left to the church and as such were obliged to keep very strict accounts. Working with the overseers of the poor they dealt with parish relief and education. They were also responsible for the morals of the parish, checking on church attendance and that children were being baptised.

The Overseer of the Poor

The overseer of the poor was responsible for setting and collecting the poor rate, which was used to give relief to needy families in the parish. The overseer was also responsible for settlement certificates, bastardy bonds and removal orders. Working with the churchwardens they were involved in education and would arrange apprenticeships for deserving poor children.

The Beadle

Dickens, in his ‘Sketches by Boz’, makes it clear that the parish and its officers and, in particular the beadle, were very low down on his list of favourite people. The beadle was a minor parish officer in charge of ushering and keeping order during the church services and assisting the churchwardens and the overseers. He wore a uniform of a buttoned coat and cocked hat and carried a staff.

“See him again on Sunday in his state-coat and cocked-hat, with a large-headed staff for show in his left hand, and a small cane for use in his right. How pompously he marshals the children into their places! And how demurely the little urchins look at him askance as he surveys them when they are all seated, with the glare of the ye peculiar to beadles!”

The Constable and the Surveyor

These two posts were amongst the most unpopular in the parish.

Before the creation of a national police force, the parish constable was in charge of raising the ‘hue and cry’ to capture thieves and criminals and guarding them in the village round house until a magistrate was available to try them.

The surveyor was in charge of the roads, lanes and drainage ditches in the parish. To help him carry out his work he could rely on the men receiving parish relief and also, although this was hard to enforce, every employer in the parish was expected to lend his labourers for two weeks every year.

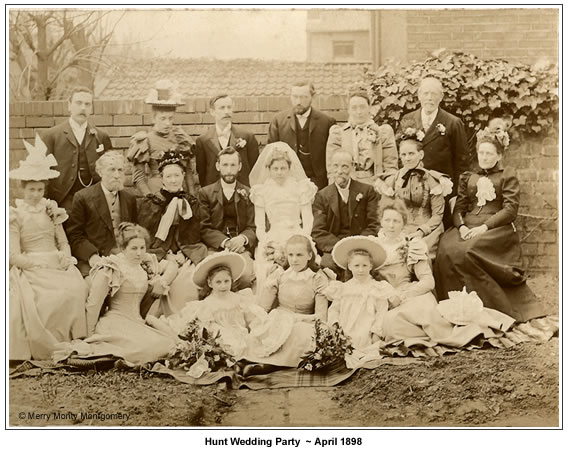

VICTORIAN WEDDINGS

On the morning of Monday the 10th February 1840 Queen Victoria married Prince Albert at the Chapel Royal, St James’. Prince Albert looked very dashing in his uniform and Victoria was dressed in white satin decorated with English Honiton lace. She wore orange blossom in her hair and diamonds around her neck. She had twelve train-bearers all wearing simple white dresses that she had designed herself. They exchanged their vows and then Albert put a wedding ring on his new bride’s finger. The ceremony was brought to an end by a joyous round of applause from the congregation and Victoria and Albert returned to the palace as man and wife. They spent a brief half an hour in each other’s company before joining their guests for an enormous wedding breakfast. The festivities were all over by four o’clock when the royal couple set off for their honeymoon in Windsor.

Their wedding was, of course, a lavish affair with a great many guests compared to the average Victorian wedding, but for all that it did contain some similarities. They married on a weekday and in the morning. Sunday had been the preferred day for weddings in the 18th century but, by the time Victoria and Albert married, weekdays had become popular. This may have been due to a mixture of the renewed interest in ritual brought about by the Oxford movement, which meant that there were now more church services on a Sunday and to the disapproval shown by the Evangelicals for excessive enjoyment on Sundays. For everyone, whether rich or poor, a marriage could only be celebrated between the canonical hours; that is from 8am to 12pm. In 1880 they were extended to 3pm. Before this date a wedding breakfast was held after the ceremony usually for the family only and, in working class communities, it was not unusual for the groom to go and do a days work afterwards. After 1880, the fashionable time to get married became 2.30pm with the wedding breakfast transformed into a large afternoon tea at about 4pm.

Victoria wore white, which, as a colour for wedding dresses, had first made an appearance in the middle of the 18th century. It became more popular as the century wore on, but other colours were every bit as acceptable especially for middle class brides who would hope to wear their wedding dress again on Sundays and when visiting for the year to come. Working class brides and grooms would wear their usual Sunday best.

A copy of the royal couple’s marriage certificate hangs on the wall of the vestry in the Chapel Royal. It was hand written by the Archbishop himself and signed by Victoria and Albert. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to discover if they were married by banns or by licence, although, for someone as important as the Queen, any good etiquette manual of the time would probably have advised a wedding by licence. Marriage by banns involved the names of the future bride and groom being read out at Sunday service for three consecutive Sundays, which was not at all suitable for the gentry. Getting a licence cost more than having the banns read and a special licence was even more expensive. It allowed the couple to be married in a different church to their parish should they wish to and at any time of the day.

Queen Victoria had twelve train-bearers/bridesmaids none of whom were children. They were chosen for their rank rather than for their closeness to the Queen but, had her wedding been a quieter affair, Cassell’s Household Guide suggests that:

“…two bridesmaids are sufficient. In the latter case it is considered complimentary to invite an unmarried sister of both bride and bridegroom to discharge the office. The principal bridesmaid is generally either a sister or a very intimate young friend of the bride.”

Then as now the bridegroom would have had a best man by his side during the ceremony. He would have been responsible for paying the various fees to the clergyman and the parish clerk after the signing of the register. Cassell’s Household Guide, suggests that the bride should take her own copy of the register from the vestry, “for which the usual fee given is half-a-crown extra” – I wonder if Victoria thought to do this?

Finally, the joyous applause that greeted the end of Victoria and Albert’s wedding was not confined to the highborn.

“Happily the sunshine fell more warmly than usual on the lilac tufts the morning that Eppie was married, for her dress was a very light one…Seen at a little distance as she walked across the churchyard and down the village, she seemed to be attired in pure white, and her hair looked like the dash of gold on a lily. One hand was on her husband’s arm, and with the other she clasped the hand of her father Silas… In the open yard before the Rainbow the party of guests were already assembled, though it was still nearly an hour before the appointed feast time…As the bridal group approached, a hearty cheer was raised…” Silas Marner by George Eliot

Georgette

© Georgette 2008