RAF Elsham Wolds in North Lincolnshire was the home of 103 and 576 Squadrons during World War Two.

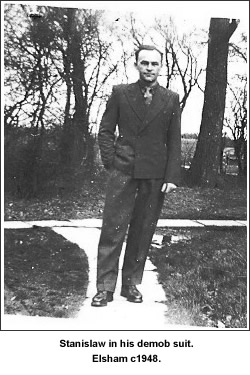

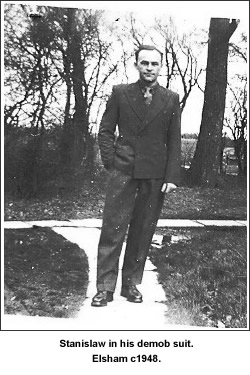

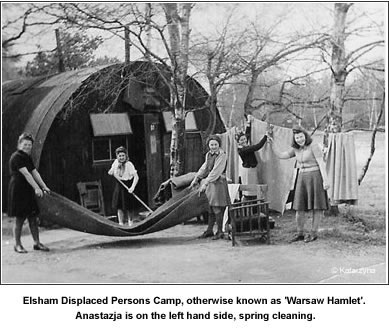

From 1948 to 1952 it was a displaced persons’ camp, known locally as ‘Warsaw Hamlet’, and home to my parents-in-law, Stanislaw and Anastazja; my husband Janusz was baptised there. The community was mainly Polish, but there were also Ukrainians and a few English people living there too.

How they arrived at the camp from their homes in Poland is a somewhat painful and long tale, however it is a story I needed to write so that my grandchildren would understand their heritage.

Researching their history has proved rather difficult; understandably they were reluctant to speak freely of their experiences during those dreadful years and, when they did so, the anecdotes were mainly of their transportation and rarely of the camps in which they were interned. Stories about the camps and the traumas to which the Poles were subjected are freely available on the internet. Using these sources I have tried to piece their story together. Weaving in the historical facts, however, proved difficult and I have over simplified them in order to tell the story of my parents-in-law, rather than the history of the WW2. Therefore any errors are entirely my own.

Researching their history has proved rather difficult; understandably they were reluctant to speak freely of their experiences during those dreadful years and, when they did so, the anecdotes were mainly of their transportation and rarely of the camps in which they were interned. Stories about the camps and the traumas to which the Poles were subjected are freely available on the internet. Using these sources I have tried to piece their story together. Weaving in the historical facts, however, proved difficult and I have over simplified them in order to tell the story of my parents-in-law, rather than the history of the WW2. Therefore any errors are entirely my own.

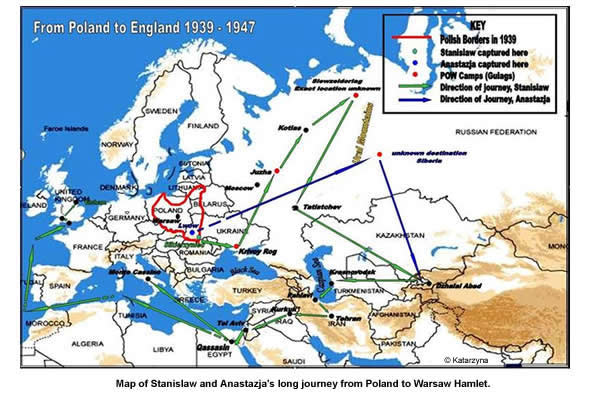

Stanislaw was born on 23rd March 1910 to parents, Wojciech and Julianna, in Trzesn, Mielec, Poland. The family farmed their own land there. Before the war Stanislaw was a member of the Polish Border Guard [1] on Poland’s eastern border. Germany invaded Poland from the west on 1st September 1939; the Russians annexed areas of Eastern Poland (Kresy) under a secret Soviet/German Non-Aggression Pact, signed by Molotov and Ribbentrop in August 1939, invading from the east on the 17th. Stanislaw was captured that day at Sikierzyniec [2] and taken to Krivoy Rog POW camp in the Ukraine.

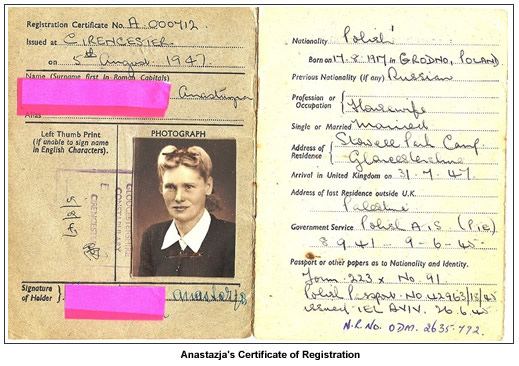

Anastazja was born on 17th August 1917 to parents, Jan Wilhelm Mickiewicz and Marja Ledochowska, in Grodno, Poland. Previous to 1918, Poland was partitioned between Germany, Russia and Austria, and in effect no longer existed as a country. There were many insurrections against their aggressors. Anastazja’s great grandfather died in Siberia. Her father and grandfather were captured during an uprising towards the end of the 19th century and although her father escaped, her grandfather spent five years in the camps.

Anastazja’s father, Jan Wilhelm Mickiewicz, was killed at the battle for Grodno Bridge, fighting the Bolsheviks in 1920. She emigrated to the USA in 1922. Her mother remarried there, but Anastazja and her brothers returned to Poland in 1924 and went to live with their grandmother in Gniew on the River Wisla in Poland.

At the outbreak of war in 1939 she was living in Lwow [3] , working as a primary school teacher. In 1940 she was rounded up like thousands of other civilians and transported for hard labour. Anastazja never saw her four brothers again; none survived the war.

Transportation and the camps

Both Stanislaw and Anastazja were transported to the forced labour camps, known as gulags, near the Arctic Circle and the Ural mountains. From Krivoy Rog, Stanislaw was moved to Camp Siewzeldorlag, in the Komi Province of the USSR, and Anastazja to the Steppes of Siberia. Despite the different camps and travelling by different routes, their experiences were very similar.

It is said that as the trains pulled out, singing along the length of the train broke out as if by command. The song was ‘ROTA’, an historic Polish patriotic form of an oath.

“We won’t forsake the land of our birth,

We won’t let them bury our language,

No German will spit in our face

And germanise our children. We, the Polish are a nation, of Polish kin

That stems from the royal tribe of Piast.

To the last drop of blood in our veins

We shall defend the Polish spirit,

Until the Russian muscovite blizzard

Shall turn into ashes and dust.

Every home shall be our fortress.

So help us God!”

This wasn’t the first time the Germans and Russians had invaded Poland.

They were packed like sardines into unheated cattle trucks; the toilet was a hole in the floor with little or no privacy. The journey was slow and arduous and they received little food or water. Some days they had nothing at all. The dead were thrown by the guards to rot at the side of the rails.

Between Krivoy Rog and the final destination of Siewzeldorlag, Stanislaw was held at at least two transit camps, Jusha and Kotlas. From Kotlas, the final destination in Komi Province near the Arctic Circle was reached, by barge and by marching through snow and ice with little protection from the elements, on 28th June 1940. For several months, somewhere and sometime in those nine months between capture and here, he worked in a coal mine. From other people’s stories we think that it may have been at Krivoy Rog, his first camp.

The Komi Forests cover 3.28 million hectares of tundra and mountain tundra in the Urals and is one of the most extensive areas of virgin boreal forest remaining in Europe; a vast area of conifers, aspens, birches, peat bogs, rivers and natural lakes with bear, wolves and wild boar. Their diet in the camp for the next fifteen months consisted mainly of bread and thin soup served, if they were lucky, twice a day. Stanislaw worked in the forests near the Arctic Circle, felling trees that were to be used for the building of roads and railway lines.

It was hard labour indeed. They worked in temperatures down to -40 degrees celsius. With so little nourishment, thousands died; frostbite, cholera, dysentery, scurvy, or other diseases took their toll. As the ground was frozen solid during the long winters, the dead bodies were piled up one on top of the other against walls, until the ground had thawed in the spring allowing for burial. The fat rats, engorged by the eating of corpses, supplemented this diet if you could catch one. If you were sick, you starved. As the communist doctrine stated, “He who does not work, does not eat”. Escape was not an option, there was simply nowhere to go. Those who tried died.

Stanislaw’s information was documented in detail on file by the NKVD (the Soviet Secret Police) and is published on the net through Ośrodek KARTA’s ‘Index of the Repressed’. It gives details of his name, father’s name, year of birth, date and place of capture and the camps to which he was transported.

As for Anastazja, we know little of where she was taken. The only information on her documents at Karta is her name, father’s name, year of birth and date and place of capture. She would not speak of those times. Her hatred for the Russians stayed with her all her life. One can only speculate what horrors she may have witnessed.

Anders’ Army

The Soviet Union was attacked by Germany in 1941, breaking the Non-Aggression Pact of 1939. Ironically this meant that Russia was now an ally of the Poles. With the help of the British, the Polish Government in exile in London negotiated with Stalin an amnesty for all Poles held in the camps.

A Polish Army in the Soviet Union was created. It was headed by General Anders, himself just released from the notorious Lubyanka prison in Moscow. The Poles were released from the camps and were again packed into cattle trucks to take them to the recruiting stations in southern USSR. Their outward journey was not too dissimilar to their arrival.

The army was to fight the Germans on their eastern front, but it became clear that the Russians could not feed or equip them. So after much pressure exerted on Moscow, the Polish troops were eventually evacuated to Persia, now modern day Iran, Iraq and Palestine, now Israel, where they were equipped and fed by the British. This was the Polish 2nd Corps, otherwise known as ‘Anders’ Army’.

Approximately two million Poles were deported from Eastern Poland to labour camps in Siberia, Soviet Asia and Kazakhstan. By the time the Germans attacked the Soviet Union in 1941 it is thought that half of the labour camp victims had died of disease, starvation or sheer exhaustion. Only about 120,000 soldiers and civilians made the trek to join General Anders’ Army, to Persia and to freedom. Many of the rest of the survivors were made ‘soviet citizens’ and worked for the state, many never to return home.

A film, written and directed by Jagna Wright, called ‘A Forgotten Odyssey’ depicts the fate of the Polish deportees.

The journey by foot, train and truck from the camps to freedom was in itself a hazardous journey; all were weak from the two years of near starvation. They were lice ridden, poorly clothed and shod, and many suffered from dysentery and other diseases. Many died on the journey. Indeed it was a far more hazardous journey to freedom than it had been into captivity.

Some Polish children, widows and families who happened to be in the neighbourhood area of the Polish Army formation, were taken under the protection of Anders’ army and were also evacuated. This was how Stanislaw and Anastazja first met. Many, however, never made the journey; unlike the soldiers they were not provided with transport and had to make their own way south. Of those who survived, women with children and the elderly were eventually placed in transit camps in Palestine, British East Africa and India.

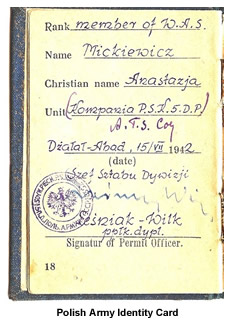

Stanislaw had enlisted in ‘Anders’ Polish Army’ at Tatistchev [4], one of the recruiting offices in 1942. General Anders waited several months at Kazakhstan for the Poles to make their way from all parts of the Soviet Union to enlist in his Army. It was in Dzhalal-Abad, Kazakhstan, that they both received their new Identity cards written in Russian, Polish and English. They are signed on the same day, 15th July 1942.

Freedom

From the Kazakhstan port of Krasnovodsk they were shipped across the Caspian Sea to the port of Pahlavi [5], Persia. Here they were transferred from Soviet control to that of the British Government, and after resting at Pahlavi, made their way to North Africa, via Tehran, Kirkuk and Palestine, where the 2nd Corps was absorbed into the British 8th Army. The Poles were given time to recuperate and retrain before going onto active duties.

From the Kazakhstan port of Krasnovodsk they were shipped across the Caspian Sea to the port of Pahlavi [5], Persia. Here they were transferred from Soviet control to that of the British Government, and after resting at Pahlavi, made their way to North Africa, via Tehran, Kirkuk and Palestine, where the 2nd Corps was absorbed into the British 8th Army. The Poles were given time to recuperate and retrain before going onto active duties.

Many Poles, however, were angered by the terms of the Yalta agreement signed by Churchill, Stalin and Roosevelt, which ultimately led to Poland becoming a satellite country of the USSR with reformed boundaries. They felt that they had been ‘sold down the river’ by the Allies.

Anastazja had enlisted as a telephonist, but drove trucks in support of the Polish units in future campaigns.

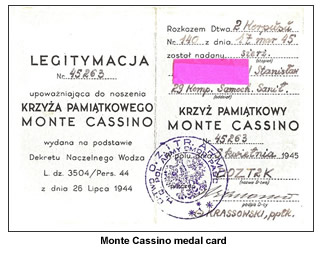

Stanislaw fought in the North African and Italian Campaigns, most notably for the Monastery at Monte Cassino in Italy in 1944, which the Polish Army captured after all others had failed. After this battle he returned to Qassasin al Azhar in Egypt to recover from his injuries.

On 16th April 1945, Anastazja and Stanislaw were married at Qassasin al Azhar in Egypt. Their first son Bohdan was born in Palestine where the Polish troops were stationed at the end of the war.

And so to Warsaw Hamlet

They were now enlisted into the Polish Resettlement Corps and, when demobbed in Britain, they, like many others, elected to make their home here. It was done with a heavy heart; the free Poland they had fought for was now in Russian hands and their safe return to Poland was not guaranteed.

For those who had survived the Gulags of Siberia, the prospect of a possible return to them was not an option to consider.

They were initially encamped at Billinghurst, Sussex, in August 1947, and then Blockley, Gloucestershire, the following year. From here they were sent to Hull in Yorkshire, and, on 15th January 1949, they were resettled at Elsham Wold, Brigg, in Lincolnshire where Stanislaw was given work at the Santon Iron Ore Mines. Scunthorpe steelworks was booming and they were short of labour.

Stanislaw’s main priorities were to keep his family together, get a job, get a roof over their heads and everything else was a bonus.

The family first lived in an air raid shelter and soon upgraded to a Nissan hut. Each Monday morning they were required to report to Brigg Police station.

Despite the conditions, especially in the cold of winter, the families lived quite well. They had their own chickens, geese and pigs, and a healthy black market existed. Anastazja made pillows from the goose feathers and traded them for paraffin. The men cured the bacon in shelters and, together with the eggs, they bartered in the local villages for butter and bread. Wood was abundantly available, so heating was free and, although rationing was harsh, they survived. Work was plentiful for the women too on the surrounding farms, particularly at harvest time.

A doctor was in regular attendance, and weddings, baptisms and Catholic services took place in the village together with traditional Easter (Jajko) and Christmas (Oplatek) celebrations. They also celebrated their Constitution Day (3rd May), Polish Independence/Armistice Day (11th November) and St Silvester’s on New Year’s Eve.

The village was a wonderful place for the children growing up; fresh air and the freedom to get up to all sorts of mischief. Lifelong relationships were established here and the sense of community was very strong.

Captain Elwes, of nearby Elsham Hall, was very accommodating to the Poles; his grandmother was Polish. He employed some of the men on his estate and allowed the families to use his beautiful grounds for their scout camps and outings, a practice which continues to this day.

In 1952, Warsaw Hamlet was closed and the families moved into Scunthorpe and the surrounding villages, or even further afield.

Stanislaw and his family made their home in Scunthorpe, and eventually in 1960 and 1961 respectively, Stanislaw and Anastazja took the Oath of Allegiance and became naturalised citizens of the United Kingdom.

The Warsaw Hamlet days were, I believe, looked back on with fond memories. It had provided a place of security and friendship for those beleaguered people. A place for them to reflect on their past and contemplate their future.

Katarzyna

© Katarzyna 2008

NOTES

<strong “>[1] Korpus Ochrony Pogranicza

[2] Sikierzyniec – now in Ukraine

[3] Lwow – now Lviv in the Ukraine

[4] Tatistchev – Tatiszczewo in Polish

[5] Now Bandar-e-Anzah, Iran

SOURCES

Personal documents, photos and anecdotes of my parents-in-law, Stanislaw and Anastazja.

Register of the Wladyslaw Anders Papers, 1939-1946.

Rymaszewski Family in Australia and World-wide. Sections 5 and 6 portray a graphic view of Polish annexation, transportation to Siberia and their ultimate journey to freedom.

Soviet Occupation of Poland 1939. This page contains in Part One, the pamphlet “The Soviet Occupation of Poland and in Part Two, stories of the deportations to Siberia.