Today we find the subject of death scary and don’t know how to deal with it or how to grieve. But go back a few generations and our ancestors were much more forthright. They lived surrounded by death; infant mortality was horrendous, there were no antibiotics, illnesses were not understood and access to doctors and hospitals was limited.

For the poorest living in overcrowded conditions, the dying were in the midst of the family, perhaps sharing a bed with the living, and the coffin would stay in the home until the funeral. How did they cope? How did they deal with it? As we look into this fascinating subject further, you will soon discover that it was sometimes in ways we would now find macabre.

The Mourning Widow

The Victorian widow bore the greatest burden of mourning. Her ‘full mourning’ had to last for a year and a day. During this period she was really not supposed to go out of the house, other than to church, and she was certainly not allowed to re-marry. Her clothing had to be dull black without any frills or embellishments, and made of crepe. This was a material which was made from silk and resembled ‘crepe de chine’, and had a tendency to disintegrate in the rain. Collars had to be plain and cuffs had to be broad, white and made of muslin. Victorian muslin was much finer than today. These cuffs were known as ‘weepers’, as the widow could wipe her nose on them if overtaken with a weeping fit. The ‘weeping veil’ was so called because it hid the grief stricken widow’s red eyes. This was also made of crepe, although breathing through it caused respiratory problems.

The less well off used bombazine, which was a slightly stiff fabric made of silk and wool. Often those who could afford it, wore dresses made of melrose or henrietta, Melrose was a linen type material made in the town of Melrose in Scotland and henrietta was a silky twilled fabric which felt like cashmere.

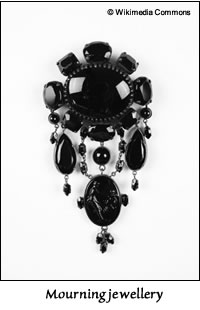

The ‘second mourning’ lasted a further nine months. During this time the widow would still be required to wear dresses made of dull cloth, but now she could add a little trim to them. Her veil was lifted back over her head and she could wear mourning jewelery. Ornaments made of hair, or containing the hair of the deceased, were very popular. Whitby jet was nearly used into extinction, with gutta-percha chosen as a cheap alternative. Gold was allowed, as well as pinchbeck, which was known as false gold.

‘Half mourning’, which lasted three to six months, must have come as a relief, although many older women would remain in ‘second mourning’ for the rest of their lives. More elaborate fabrics were allowed, and colour was gradually re-introduced into the widow’s wardrobe, such as grey, purple, lavender, lilac and, of course white. Although white was used for full mourning in hot countries.

The poor, on the other hand, had to make do. An American housewife, from Virginia, confided in her diary that the whole town smelt of dye pots. This was because it would be necessary to dye all of the widow’s clothes black as quickly as possible, so everything she possessed went into the dye pot. Then after the mourning period had passed it was common to then bleach the black out.

All this came to an end during the First World War, when hundreds of thousands of men were killed and buried abroad, whilst their wives were busy working away from the home for the first time. The art of mourning therefore quietly died away.

Cemeteries

“For there is good news yet to hear and fine things to be seen. Before we go to Paradise by way of Kensal Green”

GK Chesterton

In the first half of the 19th century the population of London more than doubled and the grossly overcrowded churchyards of inner London simply couldn’t cope with the need to dispose of the city’s dead. Horror stories started to emerge of the newly deceased being wedged in with rotting corpses or dead bodies being flushed into the churchyard’s drains, polluting the water supply and giving rise to cholera.

So, in 1832, Parliament passed a bill to close all the inner London churchyards and the ‘Magnificent Seven’ were born. These were cemeteries, not churchyards, and were spacious, pleasant and park like, situated on the outskirts of London.

They were:-

- Kensal Green (opened 1832)

- West Norwood (opened 1837)

- Highgate (opened 1839)

- Abney Park (opened 1840)

- Nunhead (opened 1840)

- Brompton (opened 1840)

- Tower Hamlets (opened 1841)

Although these were not the first cemeteries in England. The Rosary in Norwich opened on religious grounds in 1819.

The ‘Magnificent Seven’, with their wonderful monuments, were the most famous of the time, but they were not the only ones. Cemeteries were being opened up all over the country by enthusiastic Victorian entrepreneurs who were out to make money. The more elaborate and ornate the surroundings, then the more attractive they would be to the middle and upper classes.

These cities and parks of the dead could be very fancy indeed. Highgate even had a formal viewing terrace. The cemeteries had the most fashionable architecture, with Egyptian and Gothic revival, obelisks and Grecian-style temples – in fact anything your heart desired.

Some monuments tell a sad tale. Take for example Ethel Preston, whose husband built a statue of her outside the open door of her tomb, waiting for him to join her in the fullness of time, at Lawnswood Cemetery in Leeds. He remarried and she’s still waiting. Our ancestors didn’t intend death to be boring!

Death Superstitions

Christians are buried with their heads to the west and their feet to the east, as they believe that the final summons of judgment will come from the east and therefore they will be facing it face first.

However, the Victorians had a long list of superstitions associated with death. Here’s a few examples:-

- Mirrors were covered to stop the deceased’s spirit from being trapped ‘inside the looking glass’.

- Family photos were turned face down to stop the person shown being possessed by the deceased.

- The dead were carried out of the house feet first to stop them looking back and beckoning to others to follow them into death.

- If the deceased lived a good life flowers will grow and bloom on the grave. If they lived a bad life then only weeds would grow.

- A clock in a death room must be stopped to avoid bad luck.

Post-Mortem Photography

The advent of photography gave the poor a chance to have a memento of lost loved ones. Therefore there are many early photos of dead children, usually appearing asleep rather than deceased. These were not only mementoes, but tangible reminders of tiny lives. Often they would be posed with their parents or as part of the family group. This fashion and/or need blossomed in ways we would now find very strange, especially as the dead was posed, apparently alive, often in the midst of their relatives.

Victorian photographers became very adept at this. American photgraphers, Southworth and Hawes’ post mortem photos can still be found today. Photographers would advertise outside their studios stating that they would photograph the deceased in the studio or at home. They would paint eyes on the deceased’s eye lids and they would be posed on frames and dressed, possibly with a little make up applied, and the living would gather round.

The following links will take you to sites showing examples of these type of photographs.

The Editors would just like to warn readers that some of you may find the images upsetting.

The Thanatos Archive ~ Post Mortem Photography

Memento Mori – Jack and Beverly’s Cased Daguerreotype and Ambrotype Post Mortem Photographs

Petrolia – Canada’s Victorian Oil Town. The two post mortem photographs are the ones on the right hand side, half way down the page.

Just Barbara

© Just Barbara 2009

SOURCES

History of England by John Burke

Social History of England by Asa Briggs

Postmortem and Memorial Photography in the Oxford Companion to the Photograph edited by Robin Lenman

Understanding Old Photographs by Robert Pols