It could well be said that the English seaside resort was ‘born’ in 1626, when a natural spring was discovered by a Mrs Farrow (or Farrer, depending on the source), bubbling from a cliff south of Scarborough, Yorkshire. This bitter tasting mineral water was said to cure minor ailments and news soon spread of its beneficial effects, particularly after the publication of a book on the subject by a Dr Wittie of Hull in 1660.He advocated the drinking of the spa water and the submersion in the sea at Scarborough as a cure for all manner of illnesses, from epilepsy to vertigo to cleansing the stomach and lungs, not to mention hypochondria. His far-fetched claims attracted thousands of visitors to the town, providing it with the claim to fame as the country’s first seaside resort.

Meanwhile in 1750, down south in Sussex, Lewes physician, Dr Richard Russell, published ‘Glandular Diseases, or a Dissertation on the Use of Sea Water in the Affections of the Glands’, promoting the beneficial effects of the submersion in and the drinking of seawater. He had set up his practice in the county town in 1725, and had been prescribing his ‘seawater cure’ for a number of years, sending his patients to nearby Brighthelmstone for their ‘treatment’. However, his publication brought his ideas to the attention of a much wider audience, so that by 1753 Dr Russell had built himself a property in the fishing village, welcoming his patients as guests. After Dr Russell’s death in 1759 his house was let to seasonal visitors. The Duke of Cumberland (the brother of George III) was one such visitor, and in 1786 he welcomed his nephew, the Prince Regent (later to become King George IV), thus beginning his 40 year patronage to the town, including the building of the Royal Pavilion. Brighton’s future as a seaside resort was assured.

By now, news of the ‘seawater cure’ had spread around the country, and in 1781 a Thomas Clifton and Sir Henry Hoghton cashed in by building a private road to the coastal village of Blackpool, with a regular stagecoach operating from Manchester and Halifax. The Kent fishing village of Margate had been a cinque port since the 15th century. However, by the early 19th century it was developing into a seaside resort. In 1810, local author, Edward Hasted, described the shore as “… so well adapted to bathing, being an entire level and covered with the finest sand, which extends for several miles on either side of the harbour”

In around 1816 steamships were introduced all along the Kent coast, linking Margate with neighbouring ports such as Ramsgate, further increasing the area’s prosperity.

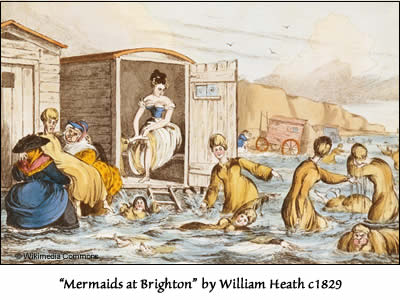

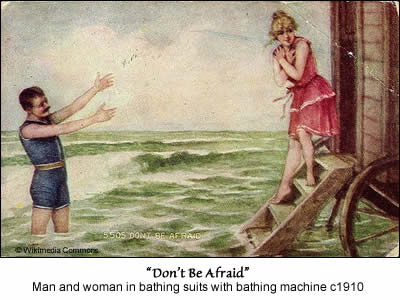

The first rolling bathing machines were appearing on Scarborough’s sands by 1735. Designed to protect the modesty of the bathers, they were wheeled down from the beach into the sea, usually by horses. The occupants would change from their normal clothing into those for bathing, putting their clothes on a high shelf to keep them dry. They would descend down steps into the water for their seawater ‘dip’.

The bathing machines in use at Margate were described in 1805 as “Four-wheeled carriages, covered with canvas, and having at one end of them an umbrella of the same materials which is let down to the surface of the water, so that the bather descending from the machine by a few steps is concealed from the public view, whereby the most refined female is enabled to enjoy the advantages of the sea with the strictest delicacy”

Some resorts employed ‘dippers’ whose job was to help the bather in and out of the water, although some were more enthusiast then others, plunging them under the waves to ‘enhance’ their experience. The most famous of these was Martha Gunn who was born in Brighthelmstone in 1726. She was a large, strong lady, both fine attributes for the job, and was a particular favourite of the Prince of Wales during his stays at the Royal Pavilion. A famous painting of her (shown opposite) depicts her holding him as a baby, although this is totally fictitious as the two wouldn’t have met until he was in his early 20s.

To Brighton came he,

Came George III’s son.

To be bathed in the sea,

By famed Martha Gunn.

(Old English rhyme, author unknown)

Once the bather had tired of their time in the sea, they would go back into the bathing machine to change and return to the shore. This bathing etiquette continued throughout the prudish Victorian period, even though most resorts enforced a strict code of segregation of sexes. Heaven forbid a man should catch sight of a woman in her bathing attire (or vice versa), although bathing costumes could hardly be described as risque by today’s standards. The use of bathing machines declined once legislation allowing mixed sex bathing was passed in 1901, so that by 1920 they were a rare sight on the nation’s beaches. However the making of these new ‘seaside resorts’ was to be the coming of the railways, bringing thousands of workers from the overcrowded and polluted cities, to the fresh air of the seaside.

Although some seaside resorts were well developed before the coming of the railway, such as Brighton, for others it was the catalyst for their growth. The line from London to Brighton had opened in 1841, and by 1849 it had been extended east to Eastbourne, later terminating at Hastings – a town already firmly on the map after a rather significant battle was fought near there in 1066, as well as it being a cinque port. But it was the railway from Brighton (as well as a line from London and another from Ashford) which led to it becoming a fashionable seaside destination.

In the early 19th century the coastline at Eastbourne was littered with a small number of fisherman’s cottages, as well as several ‘Martello’ towers, built for defensive purposes during the Napoleonic Wars. The settlement of Bourne (now called Old Town) with its 12th century church, was further inland on the lower slopes of the Downs. Even though four of George III’s children had holidayed here in the Summer of 1780, it had failed to make its mark as a seaside resort. The coming of the railway in 1849 was to turn around the town’s fortunes and led to its rapid growth. The development was planned in great detail, with the intention that it be a resort “built for gentlemen by gentlemen”. This is still evidenced today with wide tree lined avenues and a unique seafront of mainly white painted hotels.In fact resorts all along the south and Kent coasts were popular choices for day trippers and holiday makers from London, as well as Southend and Margate which were accessible by paddle steamer from the metropolis. The people of the northern industrial cities flocked to resorts such as Blackpool, Scarborough, Morecombe and Skegness. A trip to the seaside was no longer the preserve of royalty and the moneyed classes. Cheap railway transport had provided a route to the sea for the working class masses, although not all were happy. Once the railway arrived in Brighton in 1841, Queen Victoria sold the Royal Pavilion off cheap to the local council, and it went from being a royal residence to become the venue for civic functions. She, instead, preferred the relative privacy of Osborne House on the Isle of Wight, considering Brighton far too rowdy and vulgar, although the island was soon to become fashionable through her patronage.

The ‘powers that be’ in some seaside resorts saw the railway as an intrusion into their genteel way of life and did their utmost to prevent its arrival. Bournemouth is one such example – the railways finally arrived, relatively late, in 1870. In the early 1800s the coast at Bournemouth was a remote and barren heathland, known mainly to smugglers and excise men. However, in 1841, physician Augustus Bozzi Granville arrived in the area and featured it in his book ‘The Spas of England’. He advocated it as a place for those with health problems, particularly those with respiratory diseases, and it soon become the destination for invalids, as well as affluent holiday makers. Growth was relatively slow before the coming of the railways and once they arrived the town was firmly on the map. Fortunately, most resorts saw the econonic benefits of the railways and their arrival was met with huge jubilation.

Others, too, were flocking to these resorts – not for leisure, but to find work and live in these ‘new’ towns. The wealthly were taking up residence and they needed staff – domestic servants, cooks, gardeners etc. There were also many jobs created by the new tourism industry, and many came from the nearby countryside to take up these positions.

With so many destinations to choose from, competition between the resorts began to increase, with better facilities on offer, in an effort to attract visitors. The ultimate treat for the Victorian pleasure-seeker was a visit to the pier to literally ‘walk on water’. The country’s first pier was built at Ryde on the Isle of Wight in 1813, although this was not much more then a wooden jetty, which was improved on in later years. The ‘Suspension Chain Pier’ in Brighton was built in 1823 and was originally intended as a landing stage for packet boats from Dieppe, as the town was the main passenger port from France at the time, but it was soon providing facilities for tourists including a camera obscura. Brighton’s West Pier was built in 1866 and the Palace Pier in the 1890s, on the condition that the dilapidated Chain Pier be dismantled, although a storm of 1896 saved them the job.

Between 1814 and 1910 almost 100 piers were built around the coast of Great Britain. Some survive today, although many have been lost in storms, through neglect or arson. Southend’s pier holds the record for being the longest pleasure pier in the world, at 1.341 miles long. This vast length was purely for practical reasons, as the mud flats on this stretch of coast prevented larger boats landing, especially at low tide. Unwilling to allow potential visitors to continue to Margate, a woodern structure was opened in 1830, although this needed to be lengthened several times as it still wasn’t long enough. It was replaced by an iron structure in the 1870s, with a electric tramway installed in 1890, which still runs to this day. The oldest surviving pier, which was constructed of cast iron in 1860, is at Southport, Merseyside.

The latter half of the 19th century to the outbreak of World War One was the heyday for the British seaside resort. The upper and middle classes would ‘promenade’ themselves in all their finery, stopping to listen to the brass band at the bandstand, and perhaps spend the evening being entertained at a local theatre. They would stay in one of the town’s hotels – the Grand being the most exclusive, or rent a property for the duration of their stay.

The working classes (who were usually segregated from the upper and middle classes), enjoyed the sea air in their Sunday best, stayed in boarding houses, and were entertained at the end-of-the-pier show and by street entertainers such as Punch & Judy. The highlight for many would be a ride on a donkey on the beach. By the second half of the 19th century the working week was getting shorter, and workers were beginning to enjoy the luxury of a week away from work, which for many would be spent at the seaside.

As the photography process developed, day trippers and holiday makers were able to have their visit recorded for posterity with an ambrotype glass photograph taken by the numerous beach photographers.

World War One saw Zepplin raids and warships bombardments on seaside resorts mainly down the east coast, with many people killed and injured. Many soldiers camped and were trained along the south coast, and they returned to recover from their injuries. It is said that the guns of the Battle of the Somme could be heard in the south coast’s seaside resorts.

Between the wars, the more affluent started to be lured away by foreign travel, so many resorts started to modernise in an effort to attract visitors. Hastings, for example, set about a huge rebuilding project, including a new promenade with an underground car park, to cater for the holidaymaker arriving in their new motor cars. An Olympic-size swimming pool, known locally as ‘The Bathing Pool’, was also built and was considered at the time as one of the best open-air swimming and diving complexes in Europe. This was the era of the bathing pool and the lido.

In 1936, South African born, Billy Butlin, opened his first holiday camp in Skegness. He had started a fun park there in the late 1920s, and the concept of a holiday camp had come to him when he had seen families literally pushed out of lodgings, between meals, whatever the weather. He wanted to create a enviroment where the holiday maker would stay and be entertained, as well as fed. It was a huge success and the second camp was opened just two years later in Clacton. The parks were requisitioned by the military in World War Two and used for training, but a building programme began as soon as peace was declared. Camps were opened in Filey (1945), Pwllheli and Ayr (both 1947), Mosney (1948), Bognor Regis (1960), Minehead (1962) and Barry Island (1966). The company also acquired hotels in Brighton, Blackpool, Cliftonville, Scarborough and Llandudno.

It was the outbreak of WW2 which saw most of the beaches along the south and east coasts closed to the public, with barbed wire and anti tank devices installed. Piers were taken over by the military and partially blown up to hamper an enemy invasion. It would be another 6 years before the British public could enjoy them again. At the start of the war children were evacuated to the south coast, but it soon become clear that they were far from safe, and they, together with a large number of local residents, were evacuated elsewhere in the country. In fact Eastbourne was the worst bombed town along the south coast, and it has been said that it was here that Hitler intended to make his headquarters. Thankfully he never got that opportunity. As D-Day loomed the town was overflowing with troops all waiting for the off.

The post-war years saw a revival in the British seaside holiday, but cheap foreign travel was the death knell for many resorts, although many have survived and prosper, with a local economy based mainly on the service industry. As the global recession tightens everyone’s purse strings, people are looking once more at what the British seaside has to offer, and once again enjoying being ‘beside the seaside’.

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2009

SOURCES

Sources

The Seaside Holiday. The History of the English Seaside Resort by Anthony Hern

Pavilions on the Sea. A History of the Seaside Pleasure Pier by Cyril Bainbridge

Wikipedia: British Seaside Resorts

Further Reading

The Spas of England, and Principal Sea-bathing Places: Southern spas. By Augustus Bozzi Granville

For old photographs of resorts – search under the name of the town: Francis Frith

YouTube: Blackpool Victoria Pier (1904)

YouTube: Panoramic View of the Morecambe Sea Front (1901)

YouTube: Edwardian Folkestone at play 1904