When a man hires a packet boat from Dover to Calais or Boulogne, let him remember that the stated price is 5 guineas; and let him insist upon being carried into the harbour in the ship, without paying the least regard to the representations of the master, who is generally a little dirty knave. Tobias Smollett

Tobias was having the 18th century traveller’s equivalent of a bad hair day. Travelling then was most certainly not a party of pleasure. People travelled for their health, like Tobias, or for business, and the sons of the landed gentry travelled, in the words of Lord Shaftsbury to, “…polish and form the manners of our liberal youth and fit them for the business and conversation of the world”.

Travel for pleasure, as we now know it, is largely a 19th century phenomenon. With the crossing of the English Channel taking above three hours in favourable conditions and sometimes over ten in unfavourable ones, it’s perhaps not surprising that people thought twice before setting out.

In his ‘Travels through France and Italy’ published in 1766, Tobias Smollett had this to say about his crossing:- “We embarked between six and seven in the evening… We sat up all night in a most uncomfortable situation, tossed about by the sea, cold, cramped and weary and languishing for want of sleep. At three in the morning the master came down and told us we were just off the harbour of Boulogne”. It had taken him eight, long and miserable hours to get across the Channel.

So, travel was time consuming and it could also be very expensive. Even with a planned itinerary, the traveller could find himself delayed by days rather than hours and seriously out of pocket from the bribes necessary to get his belongings through border customs and the various gates surrounding large cities on his route.

In fact bureaucracy in general was a problem. Borders were constantly shifting; countries such as Germany and Italy were made up of individual states and princedoms of varying sizes with different entry regulations. Each canton in Switzerland issued its own money. Then, as now, the canny traveller could get around any currency problems by travelling with a good supply of the two popular hard currencies of the time, the French Louis D’or and the Sequin used in Venice, Rome and Florence.

Despite all these difficulties, conditions towards the end of the 18th century for travellers were getting better. The roads in Britain and across parts of the continent had greatly improved by the middle of the century, encouraging regular coaching routes and even scheduled ferry crossings. A few far-sighted individuals saw new business opportunities to be had in helping tourists and it was now possible to arrange transportation in London or Paris across much of the continent.

Travel books also began to appear. At this stage they were mostly accounts of journeys and visits undertaken by the traveller with added information on travel practicalities. Nevertheless, they were a distinct improvement on the books from the beginning of the century, which had included edifying moral essays for the young man abroad.

Travel was developing and would probably have continued to do so if the Napoleonic Wars hadn’t come along, effectively cutting off Britain from France, Italy and Switzerland for the next twenty years.

As with most things, absence made the heart grow fonder and, once peace had been restored, Britons started travelling across the channel in much greater numbers than before.British poet, Lord Byron was horrified by the number of his fellow countrymen in Italy and almost gave up on a trip to Rome in the hope that in a few years time the novelty would have worn off and the continent would be quiet once again. He was doomed to disappointment as tourist numbers increased steadily throughout the early part of the 19th century. No longer was travel the preserve of the sons of the landed gentry. Industrialisation had made Britain one of the wealthiest countries in Europe and created a new class of moneyed manufacturers and professionals eager to enjoy their lifestyle.

Industrialisation had also brought improvements to transport. The first steam ships crossed the channel in 1816. By 1821 they could complete the voyage in an astonishing two hours. The ports on the south coast were linked to the major towns of England by a series of well-maintained turnpike roads allowing for more frequent coaching services. Improvements to the structure and suspension of carriages meant that they could travel faster and ensure a more comfortable journey for their occupants. No longer would coach travellers travel twice the distance vertically and laterally as the length of their chosen route.

One of the new category of young men to set out on his travels was John Murray, son of the London publisher of the same name, famous for publishing works by Byron and Jane Austin. Inspired by the lack of detailed guides with accurate information when he set out on his continental tour in the early 1830s, John Murray (junior) saw a gap in the market and decided to fill it. In 1836 he published the first of his ‘Hand-books for travellers’, stating in his introduction that the writer, “…having experienced… the want of any tolerable English Guide Book for Europe north of the Alps, was induced… to make copious notes of all that he thought worth observation, and of the best modes of travelling and seeing things to advantage.”

His ‘hand-book’ was a success (Baedeker willingly acknowledged Murray’s influence on his famous guides), and pioneered a form for travel guides that is still with us today. The guide opens with a chapter on things to do before setting off, suggested itineraries, conversion tables for currency and timetables for steamer ships crossing the channel. Then come sections devoted to each country with general information on history, geography, customs, money, getting there and away, getting around and accommodation, followed by detailed information for visiting different towns – very similar to the layout of today’s ‘Lonely Planet’ guides.

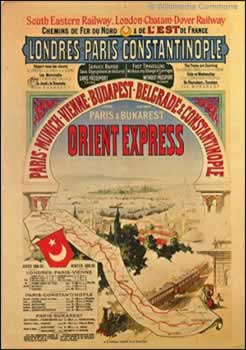

Murray’s launching of his ‘hand-book’ series, which included ten different titles by the 1850s, coincided with the expansion of the railways. Suddenly travel became faster and cheaper. The first effects of this were felt in Britain; third class train carriages on at least one train a day on every line after 1841 meant that travel was now open to the working classes.The upper classes had already been dismayed by the extension of travel to the professional classes, so you can imagine their horror when a trip to Brighton became possible for their servants. The Royal Family, who had favoured Brighton as a holiday resort, were never to return once the railway opened in 1841. Wordsworth, himself the author of a guide book to the lakes, became worried that what he perceived as ill-educated working class people, would not be able to appreciate the beauty of the Lake District and might even expect horse racing and beer shops on the shores of Lake Windermere.

Someone who was to take full advantage of the expansion of the railways was Thomas Cook. A cabinet-maker by trade, he had turned his hand to publishing temperance tracts. As a staunch supporter of the movement he covered many miles on foot to participate in the temperance meetings given in Leicestershire. On one of those long walks on a hot summer’s day in 1841, he came up with the idea of organising a train to take all those interested to the next meeting. Although he wasn’t the first to see the potential of the railways to carry large numbers of people on an excursion (from the early 1830s organised groups used trains to visit the seaside or to have a flutter at the races). Cook was to give these mere excursions a whole new dimension.

He persuaded the Midlands Counties Railway to guarantee him reduced fares in exchange for the certainty of a large number of passengers and arranged to take his fellow temperance enthusiasts from Leicester to Loughborough. Cook organised a brass brand to welcome them in Loughborough and this, coupled with the large numbers of sightseers that their departure from Leicester had generated, helped to turn his simple excursion into an event. The next three summers saw him repeat his temperance meeting trips, as well as organising excursions for Sunday school children carefully timed to take them away from their home towns during the morally intemperate days of race week.

When his temperance publishing business failed in 1846, Cook fell back on his travel business and began to expand it. He had already organised two open trips to the seaside at Liverpool the year before, which had been very successful. Now, he turned his attention to Scotland, organising a trip for 400 people in the summer of 1846. From these beginnings his business went from strength to strength, with Cook never losing sight of his desire to bring travel to the working classes to help broaden minds and promote tolerance. In 1851 around 165,000 working people visited the Great Exhibition in London on a Cook’s tour. Cook travelled round the Midlands with his son before the opening of the exhibition, persuading working people to establish ‘Exhibition clubs’ to which members could submit a bit of money every week to raise the necessary sum for the trip to London. He also gave talks and published articles encouraging working people to visit the exhibition in order that they might see the best that their trade had to offer from other regions and countries.

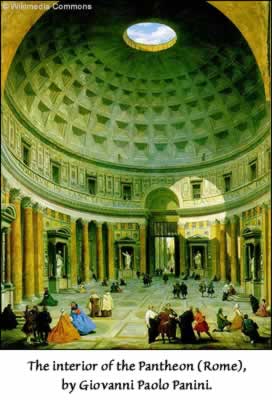

In the 1860s, Cook turned his attention to the continent and organised trips, first of all to France and Switzerland, where his ‘tourists’ could indulge in the new hobby of alpine climbing, and then to Italy. With these longer tours Cook was now catering for the middles classes who had more time to take longer holidays, although some of those early continental schedules were hardly leisurely, with each night spent in a different hotel followed by a very early start next morning.

Many who had travelled at the beginning of the century were nostalgic for the age of slow travel and the days when only the moneyed, educated elite could appreciate foreign art and architecture. Reaction to Cook’s large groups visiting the continent was surprising in its negativity. His tourists were seen to be committing the unpardonable sin of attempting to educate themselves out of their allotted station in life; they were ‘low’ and ‘vulgar’, adjectives which would surely have bemused the mix of clergymen, lawyers, teachers and their families who made up these tours. Single women were also the great beneficiaries of Cook’s tourism. Travel for them was virtually impossible under the strict social code of the nineteenth century, but by joining a Cook’s tour they could be sure of being properly looked after and of meeting other like-minded ladies and respectable family groups.

The expansion of the railways brought about an increase in the number of hotels with many of the railway companies themselves opening up hotels in some of their more popular destinations. The choice and range of comfort available to travellers increased greatly throughout the second half of the 19th century, with the last two decades seeing the establishment of the luxury travel industry. Gone were the 18th century days when the travelling nobleman’s son would have shared the local inn with the country people and their assorted livestock, and where Tobias Smollett stayed in an Italian room whose, “walls had been once white-washed: but were now hung with cobwebs, and speckled with dirt of all sorts; and… the brick floor had not been swept for half a century”.

By the beginning of the 20th century, the railways, increased leisure time, Thomas Cook and his fellow travel agents had brought the possibility of escape from everyday life, for at least a day to all but the very poorest members of society. I’ll leave it up to you to decide if Robert Louis Stevenson’s words that, “to travel hopefully is a better thing than to arrive”, still hold true now in the 21st century.

Georgette

© Georgette 2009

SOURCES

Consuming Passions ~ Judith Flanders

Grand Tours and Cook’s Tours : A History of Leisure Travel, 1750-1915 ~ Lynne Withey

Travels Through France and Italy ~ Tobias Smollett