This is an account of how I used census information, newspaper reports, assizes papers and websites as well as records offices, to trace the tragedy of William Mealing and his fiancée Sarah Moss in 1862 in Rendcombe, a small village in the Gloucestershire Cotswolds.

William Mealing was the elder brother of my great great grandmother Ann.

While trawling for her siblings on the 1881 census transcript on Family Search I found him, much to my amazement, in Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum! I knew you weren’t sent to Broadmoor for petty theft, so I was concerned that he might have been a child abuser/murderer, but I felt that I HAD to find out more.

Using Ancestry I found out that he was not in Broadmoor on the 1861 census, but he was by the time of the 1871, which narrowed things down.

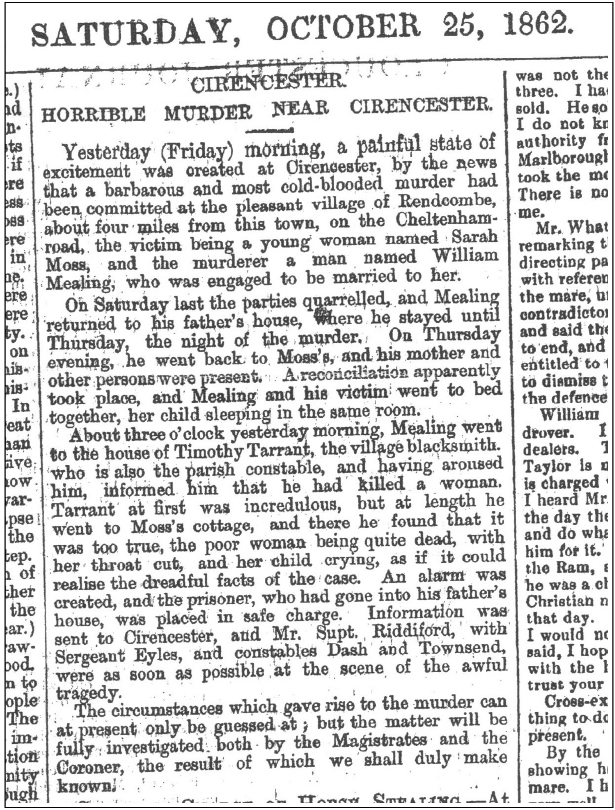

I contacted the website Murderfiles (now defunct) who were able to send e a photocopy of an article from The Times reporting on the initial hearing about the case. Now I had an exact date I could find William on Gloucestershire Council’s Genealogical Database which has Gloucestershire Gaol Register. This gave me the reference to request the entry relating to William from Gloucestershire Records Office and for the price of postage and photocopying was able to see the entry relating to William. The gaol register entry gave me a description of him, his crime and the outcome of the trial. It told me that the trial was held in the winter assizes and from this I was able to find the trial papers at The National Archives in Kew. These papers were wrapped in faded red ribbon (rather like old love letters). They had details of the date and time of the trial, the name of the judge, the jury and the witnesses called, but they didn’t contain a transcript of the trial or what the witnesses actually said.

Now that I had an exact date for the trial I was able to find the report of it in The Times newspaper which is held on microfilm at the London Metropolitan Archives. This was before I knew about The Times Digital Archive available through some public libraries, and it was just luck that whilst I was browsing in the LMA library in pursuit of some London ancestors that I happened across the microfilm! I was also able to get photocopies of the local newspaper reports from Cirencester Library for a small sum.

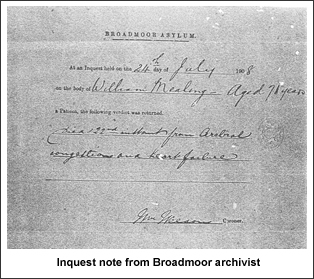

I also wrote to the Broadmoor archivist, at Berkshire Records Office in Reading. After having to send various certificates to show how I was related to William they wrote back with hardly any information about him, just a photocopy of the inquest result after his death.

William was born in 1835, eldest child of John and Mary Mealing, both agricultural labourers. The family lived in Rendcombe, a small village in the Gloucestershire Cotswolds. When William was about 8 he received a serious injury to his head as the result of some ill-treatment by a farmer. From that time his father testified that he had been unable to learn anything, that he was frequently dizzy and suffered from pains in his head.

In 1861, William, aged 27, appears on the census in Rendcombe as a lodger with Joseph and Elizabeth Williams, his sister Ann’s parents-in-law. [RG9; Piece: 1781; Folio: 79; Page: 3].

The household immediately above this is William’s parents with their younger children. Further down on the page is Timothy Tarrant, the blacksmith who was also the village constable and William’s godfather. He was to play a key role in subsequent events.

William’s future victim, Sarah Moss, is enumerated at North Cerney, a village close to Rendcombe, as a 31 year old unmarried cook, at Cerney House. [RG9/1781Folio: 87 Page:1]

Sarah had previously been in service with the Reverend Bloxome and had an illegitimate daughter who was maintained by the father (as yet untraced). This 1 year old daughter Elizabeth was living with Sarah’s deaf 77 year old father, Richard Moss, in Woodmancote, a hamlet close to Rendcombe, and they are listed as lodgers of Ann Gegg. Ann was in fact Richard’s widowed daughter, Sarah’s elder sister. [ RG9/1781 Folio: 90 Page: 7 ]

After the 1861 census, there were some changes in these households. William went to lodge with Sarah and her father before Christmas and he and Sarah became lovers. In the new year Sarah became pregnant by him. They had the banns called and were to have been married on Sunday 19th October, but William’s head trouble prevented the marriage. He and Sarah had a quarrel, as one of Sarah’s friends suggested that he was feigning illness to avoid the ceremony, and William returned to live with his parents. Sarah visited him and they returned to Sarah’s house on Thursday 23rd October, apparently reconciled. Tragically, it was the last night in their house for both of them – and for Sarah her last night on earth.

Early in the morning of 24th October 1862, Edmund Griffin, a neighbour of William Mealing’s was awoken by his door being shaken.

When he looked out of the window, William said “Somebody’s dead”.

Griffin asked who, to which William replied “Sarah Moss and I want you to get up and take me to be hung”.

Mr Griffin responded “None of your antics”.

“Then you won’t take me to be hung?” asked William.

“No, if there’s a man to be hung, there’ll be time enough for that in the morning”.

Edmund was clearly not impressed at having his sleep disturbed, and in the dark could not see that William’s shirt was drenched with blood.

William then went to his godfather, Timothy Tarrant, the village blacksmith and constable and said “I am come for you to take me up and hang me, for I have been and killed a woman”.

Mr Tarrant took the man to his parents’ house and then went on to The Kennels, the house where William lodged with Sarah Moss, and roused Mr Griffin again, together with another neighbour, Joseph Robins. There was no light coming from the house, so Tarrant and Robins went in and up to Sarah’s bedroom. They found her lying on her stomach with her throat cut and her head nearly severed from her body.

In the same room was her 3 year old daughter Elizabeth Louisa, who was crying. One newspaper account describes “…blood, which was running through the floor into the room below”.

The constable and neighbours tried to break the awful news to Sarah’s elderly father, but he was very deaf and only thought that his daughter had gone into labour.

William appeared before the magistrates on the Saturday at Cirencester. Evidence was given by his parents, John and Mary, his sister Emma, Timothy Tarrant, and Richard Daniel Larke, a surgeon who had previously attended William and who had been the first medical man to view the body. William was committed for trial on the charge of “wilful murder”.

Trials then were held more swiftly than nowadays. William’s was heard in the course of a morning at Gloucester Magistrates Court on 16th December 1862.

Between the magistrate’s hearing and the trial, the villagers of Rendcombe raised money to pay for William’s defence. His mother, whilst very upset, gave evidence that on the fatal night he had been persuaded to return to live with Sarah, although he was still complaining that his head was bad and had said to his mother earlier that, “I am very afraid that it will drive me out of my mind”. His mother had cautioned Sarah to keep any knives away from William, but she had not known about the razor with which she had been killed.

William was represented in court by Mr W H Cooke, whose fee was paid through a collection by the Rendcombe villagers, who had presumably realised that poor William wasn’t responsible for his actions. It is a sobering thought that without this effective defence, William might well have been hanged for his actions.

Mr Cooke called William’s parents, who testified to the long-standing effects of his childhood injury, as well as three expert witnesses: Mr David Ruck of Cirencester, who had attended the prisoner; Mr Hicks, the surgeon at Gloucester Gaol and Dr Adamson, previously a surgeon at a lunatic asylum. They were of the opinion that the prisoner was of unsound mind when he committed the offence and that he was suffering from homicidal/religious mania.

After a brief deliberation, the jury found William Mealing not guilty, on the grounds of insanity.

William remained in Gloucester Gaol, closely observed (presumably on suicide watch?) until 6th February 1863 when he was transferred to Bethlem, the notorious lunatic asylum in London (now the building housing the Imperial War Museum).

This was a temporary move, as on 23rd July 1864 he was conveyed to his final home – Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum, near Crowthorne, in Berkshire. Broadmoor had recently been purpose-built and William was one of the first intake.

He remained at Broadmoor for the rest of his life, which was another 44 years. This is a long time in which I know nothing of William’s life – my next avenue to research.

He died on 22nd July 1908, just a day before the anniversary of his arrival at the institution. The compulsory inquest held two days later concluded that he had died of cerebral congestion and heart failure. He is buried at Broadmoor in an unmarked grave.

William’s parents continued to live in Rendcombe. Mary died in 1882 of heart and kidney failure, and her husband John died in 1884 at Cirencester workhouse. His cause of death was recorded as “committed suicide by cutting his throat with a razor – lived 20 days”.

Sarah Moss’ illegitimate daughter Elizabeth Louisa, was raised by Sarah’s older widowed sister Ann Gegg. She married Edward Phillips in Kent in 1880 and appears on the 1891 and 1901 census returns in Hastings, Sussex, with her husband and her mother’s married sister Charlotte Lewis.

Rendcombe was a small village and the main protagonists of the events in 1862 are living within a page or so of each other on the 1861 census. From evidence at the trial and from the fact that money was collected for William’s defence, shows that the villagers knew William wasn’t responsible for his actions.

It was probably only through their generosity that William’s defence obtained a verdict of innocence, and if he’d been found guilty, that he would very likely to have been hung.

Although I knew nothing about this when I began my research, most of the villagers would have carried it in their memories. An interesting footnote is that Timothy Tarrant’s descendants continued his blacksmithing trade and one of them apprenticed William Mealing’s great great nephew – my grandfather Angus Williams. Another connection which I’ve found is that my great great grandfather John Purvey’s third wife Emily Gegg was the granddaughter of Ann Moss, Sarah’s sister.

I am waiting for the release of the 1911 census to see what happened to Elizabeth. I also plan to visit the Bethlem Hospital Archive and to find out more about William’s experiences in Broadmoor.

Finally: A spooky footnote

Through researching this story I was put in contact with the Rendcombe parish clerk, who by coincidence lives in The Kennels, now just one residence. She told me that there had been ghostly stories about a ‘grey lady’ who had been seen in the house. During extensive alterations, a cut throat razor similar to the one used by William Mealing (and later his father) had been discovered plastered into one of the walls. After this discovery the grey lady made no more appearances. Sleep well!

Little Nell

© Little Nell 2008

Newspaper sources:

GLOUCESTER JOURNAL

The Times 25 Oct 1862; 28 Oct 1862, and 18 Dec 1862

Gloucestershire Chronicle, 25 Oct 1862

Gloucestershire Journal 25 Oct 1862

Wilts & Gloucestershire Standard, 20 Dec 1862