About half of my ancestors on my father’s side of the tree lived in Australia; some of their forebears had emigrated from Ireland, some from Kent and some from Yorkshire. It was among them that I expected to find one or more convicts, but so far, all of them have turned out to be economic migrants. When a convict did appear, it was in an unexpected quarter: on my mother’s side of the tree, which has no obvious connection to Australia.

I’d been researching the Sparkes family in the village of Fillongley, near Coventry and had discovered a website called ‘Coventry Collections’, which contains some interesting archives relating to Coventry and its surrounding district.

When I entered the surname Sparkes in the database, I found one or two apprenticeships for Sparkes boys from Fillongley; a James Sparkes who was an overseer of the poor in Fillongley, and one entry that sparked my interest, so to speak, which was a reference to a Benjamin Sparkes of Coventry, who had been convicted for machine breaking.

There are four people in my tree with the name Benjamin Sparkes or Sparks, and this was obviously none of them, because they were all born much too early. However, as the name is not a very common one, I decided to investigate further, in case this Benjamin was connected to my Sparkes family.

No definite connection has yet emerged, but this is the story so far.

Benjamin Sparkes was born about 1812, probably in Coventry. He worked as a whitesmith in Spon Street, making pots and pans and such like from tinplate or pewter.

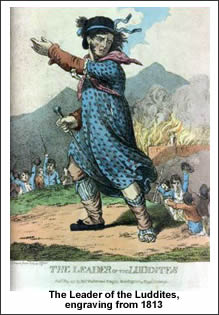

Luddism had been rife in England since the early part of the century, when steam-powered looms were introduced. Agricultural machinery was destroyed in the Swing Riots of the early 1830s, and one of the last major episodes of industrial machine breaking took place on 7th November 1831.

A large group of men (contemporary estimates range between 200 and 700) gathered in Coventry to discuss the state of the weaving industry. Feelings were running high, because the industry was depressed, and handloom weavers were reduced to dire poverty. Their average wage had plummeted from 27 shillings in 1800, to 5/6d by 1831.

Josiah Beck had recently installed a steam engine and his looms were felt to be putting men out of work. The angry weavers converged on his factory and he agreed to admit a representative, but when the door was opened the mob rushed in. Beck was beaten, his machinery smashed, and the factory set on fire.

Why Benjamin Sparkes joined in the rioting is unknown. He was not a weaver, but perhaps friends or relations of his were. Whatever the reason, he appears to have been one of the ringleaders of the riot. He was arrested, and charged with Thomas Burbury and others, with unlawful and riotous assembly and destroying Josiah Beck’s house, machinery and steam engine.

The men were tried at Coventry assizes on 24th March 1832. Witnesses testified that they had seen Sparkes smashing a steam engine with a hammer and destroying looms. He and Burbury were found guilty.

The offence was obviously a serious one, but no-one had been killed, and nowadays one would expect a sentence of imprisonment. However, in an attempt to prevent Luddism from spreading, the Government had introduced the death penalty for machine breaking in 1812. The judge reached for the dreaded black cap, solemnly put it on, and passed sentence of death, ordering that the men be “hanged by the neck until dead”. Benjamin Sparkes was just 20 years old.

Sparkes and Burbury were due to be hanged on 11th April. There was a public outcry, petitions were signed and letters written. They were reprieved with just a few days to spare. The death sentences of both men were commuted to transportation to the colonies for life.

Thomas Burbury was shipped off to Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania), whereas Benjamin Sparkes was sent out to New South Wales on a ship called the ‘Planter’, which sailed on 13th June 1832 carrying 200 convicts and arrived in Sydney on 15th October.

After serving part of their sentence, transported convicts could apply for a ticket of leave, which allowed them to resume a normal life to some extent: they could seek employment, and even marry, although they were not allowed to leave the district where they lived without permission. After a further period of good behaviour, they could apply for a pardon or a certificate of freedom.

Benjamin Sparkes was first granted a ticket of leave, and finally, on 30th September 1847, after serving 15 years of his sentence, he was granted a conditional pardon. This meant that he was free, provided that he remained in the colony. He was not eligible for a certificate of freedom because he had been sentenced to transportation for life. He could not legally return to England which would have been not only a breach of his conditional pardon but also a hanging offence.

What happened to him next, I have not yet discovered. There is no trace of his marriage or death in the New South Wales BMD indexes, nor in the English censuses or BMD indexes. He may, of course, have changed his name, and either remained in Australia or returned illicitly to England, or may have moved to an Australian state which does not yet have its birth, marriage and death indexes online.

His trade, as a whitesmith would no doubt have been in demand in the young colony, and it is to be hoped that he made a new life for himself in Australia.

Mary in Italy

© Mary in Italy 2008

Research sources:

Ancestry: Australian Convict Transportation Registers – Other Fleets & Ships, 1791-1868

Further reading:

The Price of Bread: Poverty, Purchasing Power, and The Victorian Laborer’s Standard of Living