John James Leadbetter, my great great grandfather, began his life of notoriety in a suitable manner.

On 11th April 1830, his mother, Elizabeth Burns, a seamstress in Tulliallan, Perthshire, was summoned before the parish Kirk session, where the minute book covering the period (1828-1832) states “Compeared [sic] [summonsed] Elizabeth Burns, who after being exhorted to tell the truth, confessed she was with child to John Ledbettor [sic]”.

A second summons on 9th May 1830 issued to both the accused parties states: “Compeared [sic] also Elizabeth Burns and John Leadbettor [sic], who being exhorted to tell the truth declared that she was with child before he knew her, admitted that he had had dealings with her but denied that he was the father of the child”.

Elizabeth Burns declared that the ‘guilt’ was committed in her father’s house on “the last Sabbath, or last but one in December” and at other times after that. John Leadbetter admitted that her statement in relation to time was correct and that if the birth corresponded with that, he would acknowledge the child as his. It appears that he did admit responsibility, as the child was henceforth known by his father’s name.

My next sighting of Elizabeth was in 1841, at the time of the census, still living unmarried in Tulliallan, working as a seamstress and apparently sharing the home with her siblings, as well as her son, 10 year old John Leadbetter.

Fast forward to the 1851 census, and young John James Leadbetter, described as an ostler, spent census night in Dunblane prison. Further enquiries revealed that John Leadbetter, prisoner number 5385, had received a 10 year sentence for house breaking. The records of the High Court of Justiciary show that on Sunday 2nd March 1851, he had broken into a house at Knowhead, Kincardine and stole £11.10/-. This was the house of grocer, George Ainslie, and was not far from his mother’s home.

John served five years of his sentence in Portsmouth prison and was then released on a ticket of leave. He was armed with a letter from the governor of the prison that stated “John Leadbetter, prisoner no. 1045, has served separate confinement for 17 months and nine days, his conduct being good, and public works for two years eleven months and twenty six days, his conduct being very good”.

Alas, he could not sustain such a level of virtue. Whilst on his ticket of leave, on his way back home to Scotland, he fell into trouble again.

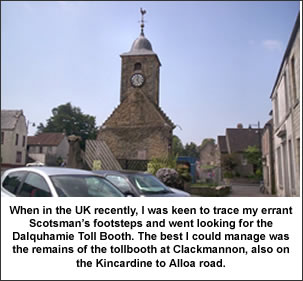

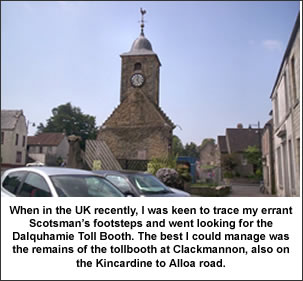

Between 1.00am and 2.00am (when God-fearing Scots should have all been in bed), on Wednesday 9th July 1856, he assaulted the taxman Neil Thomson at the Dalquhamie toll house on the road from Kincardine to Alloa “using a stick and a sizeable stone to inflict severe injury with the intention to rob”.

For this offence he was sentenced to transportation to Australia.

Since the only colony still accepting convicts by this time was Western Australia, this is where he went, arriving on the convict transport ship ‘Sultana’ on 19th August 1859.

Prisoner no.5385 was described literate, Protestant, single, no children, 5’10” in height, light hair, light hazel eyes, full face, fair complexion, middling stout build and a scar under his left eye.

Perhaps he had learned to behave himself – on the 30th January 1860, he once more received a ticket of leave, which permitted him to seek employment on his own behalf in the colony. By July 1861, his sentence was deemed to have expired and by 13th December 1863 he had married Lucy Ellen Glover, the daughter of William Glover, a free settler who had been one of the pioneering families of the colony. The marriage took place at Gingin, a small town 83 km north of Perth and the couple went on to produce a family of seven children, one of whom was my great grandmother, Jane Leadbetter.

He does not seem to have appeared in the official records after gaining his freedom, so perhaps his transportation was actually beneficial. He died in 1905 aged 74 years. The family lived largely around Jarrahdale, (a timber town initially), and generations later, has become an extensive clan of solid and upright citizens.

I am not sure that my grandmother ever knew about the convict in the family. Commonplace as such things were in Australian society, it was for generations deemed to be shame-worthy. It is only in very recent times that possessing a family convict lends a certain cachet to one’s family tree and I am grateful it did not become my lot to break the news to my very upright grandmother.

Macbev

© Macbev 2008