When the First World War broke out, my grandfather Denis, his wife and two children, and his two brothers and one sister were all living together in Croydon Park, Sydney, Australia, in what had been their late parents’ house. Denis had a family to support, but his brothers Matthew, 30, and Thomas, 24, were single and free to join up, which they did.

Thomas joined the No. 1 Light Horse Regiment of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) in 1914, and Matthew joined the 2nd Divisional Signals Company in 1915. According to their attestation papers, in civilian life Thomas was a painter and Matthew was a plumber, and they had both served 5 year apprenticeships. Thomas gave his brother Denis’ name as next of kin, and Matthew gave his sister Margaret’s name.

Thomas served with his unit in Egypt, Gallipoli and Malta. He received several temporary appointments as Corporal while acting as an instructor, but on each occasion reverted to the rank of Trooper at the end of the appointment. No misconduct is mentioned on his file, apart from a severe reprimand for irregular conduct on parade, so he was presumably promoted whenever his services were required as an instructor, but on a purely temporary basis.

Apart from his fluctuating rank, his war service appears to have been relatively uneventful, although he spent several short periods in hospital suffering from ‘debility’.

Another member of the family, Denis’ wife’s brother-in-law Jack, who is recorded as a miner on his attestation form (although he also starred as a high wire artiste and tap dancer in his parents’ travelling show), had joined the 45th Infantry Battalion of the AIF in 1915, when he was 31 years old. Jack’s war service was somewhat patchier than Thomas’. He spent numerous periods in hospital with a variety of medical conditions, including strained back muscles, neuralgia (shellshock), a leg wound and trench fever. His unit served in France, and he was twice shipped to hospital in England, returning to the trenches every time.

In the British Army, desertion was a capital offence, and many frightened young men faced firing squads as a result. But in the Australian army the only capital offence was mutiny; desertion did not attract the death penalty. The Australian troops had something of a reputation for being undisciplined,

and a look at the service records on the National Archives of Australia website shows numerous examples of men who went absent without leave for days at a time.

Jack was no exception. The first time he went AWOL he was missing for 2 days. When he returned, he was sentenced to 3 days Field Punishment no. 2 (see side panel) and forfeiture of 3 days pay. On another occasion he was AWOL for 5 days, sentenced to 14 days FP no. 2, and forfeited 19 days pay. There are half a dozen of these episodes on the file: some in Egypt, and some in England. Whether he returned under his own steam on each occasion or was picked up by the military police, the file does not say. Presumably a man who had gone AWOL while at the front would have been treated more harshly. Despite these misdemeanours, Jack was awarded the full complement of three medals at the end of the war.

Matthew got into much more serious trouble. The very first entry on his file shows that he was cautioned for being absent from duty in the depot orderly room. Shortly afterwards he was shipped out with his unit to Gallipoli. From there they were sent to France, where he was gassed, and sent back to England for treatment. He spent some time in hospital, and it was after his discharge that he blotted his copybook. The National Archives of Australia have two files for him: the usual service record, and a court martial file.

The court martial record shows that a formal hearing was held in Dunstable, Bedfordshire, England, on 18th May 1917, at which Matthew was represented by a solicitor. He was charged with (i) when in arrest escaping; (ii) when on active service striking his superior officer, and alternatively (iii) attempting to strike his superior officer. He pleaded not guilty to all three offences.

A number of witnesses gave evidence. There were said to have been complaints of trouble caused by Australian troops in nearby Fenny Stratford. Matthew was alleged to have been involved in a disturbance in the town earlier in the evening, and the town picquet (military police patrol) arrested him and two other men at the Cosy Corner restaurant.

The picquet were supposed to escort the men back to camp, but Matthew suddenly broke away from the escort, and punched the sergeant who went after him.

After a scuffle, during which the sergeant claimed to have been bitten, Matthew was rearrested and marched to camp with the other men.

After hearing all of the evidence, the court martial found him guilty of the first two charges and not guilty of the third. On 23rd May 1917 he was sentenced to 112 days detention, 56 days of which were subsequently remitted, and forfeiture of 72 days pay. Two months later he was back at the front in France with his unit.

Why the whole sorry incident happened is not known. There is no mention in the file of drink being involved, and Matthew had a reputation for sobriety in later life, but it seems the most likely explanation.

Whatever the case may be, Matthew certainly redeemed himself on his return to France. He rejoined his unit on 12th August 1917, and just two months later was recommended for the Military Medal.

The recommendation states that while Matthew, a sapper, was superintending the burying of a cable with a sergeant, the party was heavily shelled twice, with high explosive and mustard gas. Throughout the time it took to joint and repair the cable, Matthew and the sergeant were exposed to great personal risk. Matthew was commended for his “personal courage and absolute disregard for danger”, which “set a fine example to the digging party”.

The award of the medal was published in the London Gazette on 12th December 1917, and in the Commonwealth of Australia Gazette on 2nd May 1918. Whether or not Matthew’s family were aware of the court martial is unknown, but if they did find out about it, the award of the medal hopefully wiped out the shame that they would have felt.

Mary from Italy

© Mary from Italy 2008

Picture of Military medal from NZDF and subject to Crown copyright.

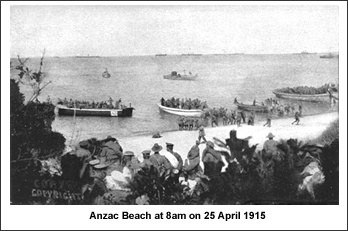

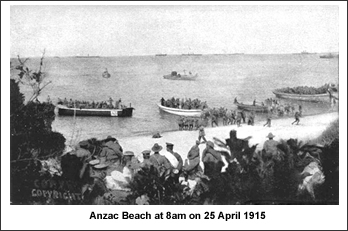

Picture of Anzac Beach from Wikipedia Commons.

Crime and punishment among the troops in WWI

Field punishment

In the Australian forces during WWI, field punishment could be awarded by a court martial or commanding officer.

Field punishment No. 1: the offender was shackled and tied to a post or wheel (this was sometimes known as ‘crucifixion’).

Field punishment No. 2: the man was shackled, but not tied to a fixed object.