Written from material supplied by Margaret in Burton

© Velma Dinkley 2008

Burton on Trent

Burton Upon Trent can trace its brewing roots back to the 11th century, and during the latter half of the 19th century, a quarter of all beer sold in Britain was brewed in the town. Burton stands on the River Trent on the A5121 and close to the A38 and A50 trunk roads. It is situated in Staffordshire, but is very close to the border with Derbyshire.

St Modwen, a nun and saint, founded a religious community in the area in the 7th century; she is buried on Andresey Island in the River Trent. The parish church in the market place is dedicated to her, as is the Roman Catholic church of St Mary and St Modwen. The local branch of the sea cadets is also named after her, TS Modwena.

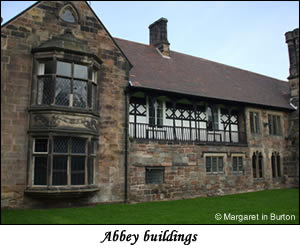

Wulfric Spot, a Saxon nobleman and a descendant of Alfred the Great, established an abbey in Burton, alongside the river, in around 1002. There was a settlement here long before this, as prehistoric artefacts have been found in the area. The abbey prospered and the monks brewed ale, using the later to become famous Burton water, which comes from deep underground artesian wells, and owes it’s hardness to the limestone and gypsum deposits in the area. This was the first recorded sign of Burton’s forthcoming reliance on the brewing industry.

Burton is briefly mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086, as the abbey owned land in 18 different manors across Staffordshire and Derbyshire. Villagers who held land belonging to the abbey worked one or two days a week on abbey estates in return for their land, of usually around 30 acres. The abbey was to fall prey to the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII in 1539, the last abbot, William Edys, having been in his position for only six years.

Only some of the abbey buildings remain today, these include the abbey’s original entrance which is fitted into the wall of the Coopers Square shopping centre. Unfortunately, a local stonemason, not understanding Latin, made quite a mess of repairing the lettering when the shopping centre was built.

King John granted a charter to Burton in 1204 giving borough status. This allowed a weekly market and a fair to be held on the first Monday after Michaelmas. The fair started as a means for hiring servants, although it’s now operated as a funfair by Pat Collins Fairs, and is held in the Market Place and part of the High Street, Lichfield Street and New Street. The world famous fairground ride manufacturer, Orton and Spooner, was once based in the town.

Alabaster was quarried from nearby Tatenhill and Fauld, and the area was quite famous many centuries ago for the carving of religious objects. Sadly this declined.

William Wigston (or Wyggeston) of Leicester owned much of the land in the Horninglow area of Burton. He was born in 1467 and was a merchant in the French port of Calais, when it was controlled by the English. He founded a hospital in Burton, and the present Queen’s Hospital, formerly the local workhouse, was built on land which once formed part of the Wyggeston estate. Many place names in Horninglow are references to William, such as Calais Road and Dover Road.

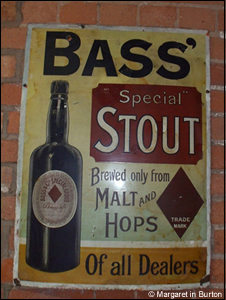

Mary, Queen of Scots was supplied with ale from Burton during her imprisonment in nearby Tutbury Castle. It is said that she was kept aware of conspiracy plots by sympathisers’ notes smuggled in with the beer.

An Act of Parliament of 1698 allowed the navigation of the River Trent up to Burton and this was the first direct means of transportation to other areas. Trent navigation connected Gainsborough with Hull and then Hull to the Baltic ports. By 1748 a considerable trade had been established in the Baltic and via St Petersburg. Both Tsar Peter the Great and Empress Catherine were said to have enjoyed the beverage. The opening of the Trent and Mersey canal in 1774-5 opened up an additional means of transportation with Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and beyond.

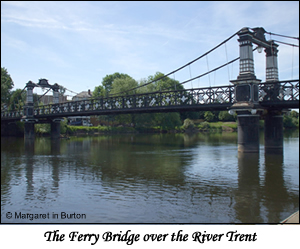

A river crossing was first built over the River Trent in the 12th century, and a ferry at Stapenhill began in the 13th century and continued until 1889 when the ‘Ferry Bridge’ was built by the local engineering company, Thornewill and Warham. Lord Burton, Michael Arthur Bass, the owner of Bass Brewery, paid for its construction.

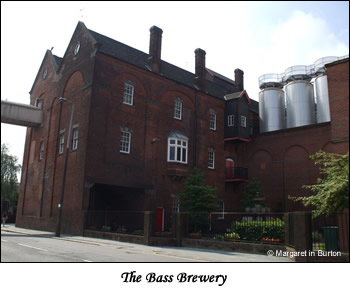

He had taken over the running of the Bass Brewery from his father Michael Thomas and his grandfather William, who had set up the brewery in 1777. He was a good friend of King Edward VII who often visited the area, which led to him brewing the famous King’s Ale in 1907. Edward stayed at the Bass family home, Byrkley Lodge, which was located just outside Burton, and his mistress Alice Keppel sometimes accompanied him.

Benjamin Wilson opened Burton’s first commercially operated brewery in 1708. His daughter married a James Allsopp and it was their son Samuel Allsopp who put his name to the brewery.

Burton is also the home to rubber companies such as Pirelli, as well as to food producers. Marmite & Bovril, both by-products of the brewing industry, are still made in the town, whilst the production of Robirch pies and sausages and of Branston Pickle, named after a local village, has since been moved out of the area.

However, it was the brewing of beer which brought the most prosperity to the town, for which it became well known. At it’s height, in the latter half of the 19th century, there were over 30 breweries in Burton with well over half the working population working in the brewing industry. In fact, one quarter of all beer sold in Britain, at the time, was produced here.

In the early 20th century, there was a slump in beer sales, partially due to the Liberal Government’s anti-drinking policies, and this led to many breweries either closing or amalgamating, so that by 1928, only 8 breweries were operating in the town.

The Worthington Brewery, started by William Worthington in 1744, merged with Bass in 1926, and was later amalgamated with Mitchells and Butlers of Birmingham in 1961 and with Charrington’s of London in 1967.

Allsopps brewery merged with the adjacent brewery, Ind Coope, in 1934. There were many more take overs and mergers over the years with Tetley Walker joining them and being renamed ‘Allied Breweries’. In turn they were taken over by Carlsberg, and it became known as Carlsberg Tetley.

Marston’s was an amalgamation of Marston, Thompson and Evershed among others and in recent years taken over by Wolverhampton and Dudley Breweries, although it is still known by the Marston’s name.

Bass bought the Carlsberg Tetley brewery site in Burton in 1997, although the Monopolies Commission blocked a take over. The bigger brewery with the Bass name was sold to Interbrew of Belgium, however this was also blocked and Interbrew kept the Bass brand name and sold the Burton brewery site to Coors of the USA.

The brewing museum in Burton began life in 1977 as The Bass Museum, to celebrate the bicentenary of Bass. It was centred around the old Bass joiner’s shop and was opened by her HRH Princess Anne. It contains 200 years of Bass vehicles and artefacts, as well as the award-winning Bass shire horses. The story of the history of brewing in Burton is described throughout the museum, with a working model of the brewery railways as they were in 1921. When Bass sold the Burton brewery site to Coors, the museum became known as The Coors Visitor Centre.

They announced in March of this year that the museum would close at the end of June and all artefacts, as well as the famous shire horses, would be either sold or divided between other Coors’ sites. This caused uproar in the local area and beyond, and plans to stop the move are afoot. A working party headed by local MP, Janet Dean, is trying to get charitable status for the museum. Coors has agreed not to move anything until at least the end of the year, although the shires have been put out to pasture in the local area. They have also pledged to donate the building to any successful business plan, together with a cheque for £200,000. A petition of 20,000 signatures was organised by the Burton Mail newspaper and this has been handed to the Culture Minister, Margaret Hodge, with a call to make the museum ‘The National Museum of Brewing’. She has called upon businesses and the local authority to pledge financial support for the upkeep of such a museum. Apparently there are talks ongoing, although details of which have yet to be announced.

SOURCES

Burton upon Trent – A History by Richard Stone

History of Burton upon Trent by Charles Hayward Underhill

Brewery Transport in Burton

The railways first arrived in Burton in 1839, with the coming of the Birmingham and Derby Junction Railway, and this provided another means to transport the beer away from the town other then the River Trent.

However, Burton itself was cross-crossed with a 17-mile network of railway lines and crossings, owned solely or jointly by the main breweries, Bass, Worthington, Allsopps, Ind Coope, Marston and Peter Walker, as a means of transporting goods around their various sites.

I can remember as a child having to wait at crossings in the High Street, Station Street and Horninglow Street for a locomotive and its trucks to pass.

Bass alone owned nine locomotives, and in one year 100,000 wagon loads of beer were despatched from their brewery, with an average of 7000 casks a day.

Heavy horses, such as Shires, Clydesdales and Suffolks were used around the brewery to haul goods and to deliver the beer to the local pubs. In the early 20th century there were 200 horses in Bass’ stables, however as motor transport was gradually introduced, their number dwindled, so that by 1921 there was 120, and by 1931 there was just 36.

There were three shire horses, Carling, Reef and White Shield, at the museum until it closed earlier this year and they have now been put to pasture until the museum’s future has been decided.

Whilst the museum was open they sometimes were used to deliver small amounts of beer around the town, as the photograph opposite shows.

Whilst road transport was replacing the work of the horse and dray, it also led to the eventual closure of the brewery railway network around the town. The museum has a vast array of vehicles used by the breweries such as trucks and vans, but also exhibits cars and buses, as well as horse drawn wagons and carriages from earlier times.

The photograph on the left is of my grandfather, Edgar Newey (left), by the Worthington Bottle Car in 1934, outside the ‘The Acorn Inn’ in Burton which he ran with my grandmother. You can read their story in the August issue of the magazine (Oldest licensee). The car is now in the museum.

Brewery Workers

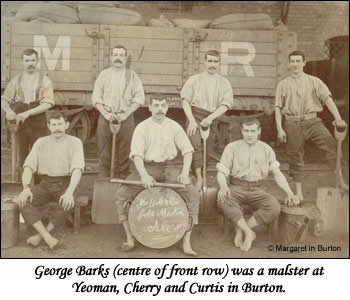

In the latter half of the 19th century, over half of Burton’s working population was employed by the brewing industry, and one of the highest paid labourers was the malster. The malster worked in temperatures as high as 130 degrees Fahrenheit, manhandling 16-stone bags of barley up several storeys for the germination and malting process. Once the barley had germinated, it was put over a kiln on a tiled floor, with holes in the tiles to allow the heat through. This stopped further germination and dried the barley, thus producing malt. Different strengths of beer needed various lengths of time in the kiln. The final stage of malting was to remove the roots which was done by sieving. It was then ready to go to the brewery.

Even though it was well paid work, many local men would avoid the job because of the tough working conditions, so migrant workers (known as ‘Norkies’) were brought in from East Anglia.

They began coming to Burton between 1860 and 1870, when the breweries were rapidly expanding and the railways made travel both quick and affordable. The agricultural depression in East Anglia had left many labourers unemployed during the winter months, when it was the malting season in Burton. So brewery agents would go to Norfolk and Suffolk and recruit Norkies in the local pubs and pay their single fare to Burton.

Their numbers increased during the late 1800s and early 1900s, so that by the time of the 1901 census, 636 norkies were recorded as working in the brewing industry in the town. This continued until the economic depression of the 1930s when their jobs were given to local unemployed men.

Malsters worked seven days a week. The basic wage in the early 20th century was 4 shillings for each weekday and 5 shillings for Sundays, with extra payment for early mornings and an end of season bonus. It was Norkie tradition at the end of a season to buy a suit from Tarvers, a local outfitter, and a ‘Norkie teapot’ made by T G Green of Swadlincote.

If you are ever having problems locating a Suffolk or Norfolk born ancestor on a census return, then try looking for them in Burton, as he could well have been a Norkie.

The photograph opposite shows my great grandfather, George Barks (centre of front row), who was a malster at Yeoman, Cherry and Curtis in Burton. Unlike many malsters, he was not a Norkie and had been born in Balderton, Nottinghamshire, in 1878, where he had been employed by the James Hole and Co brewery before moving to Burton.

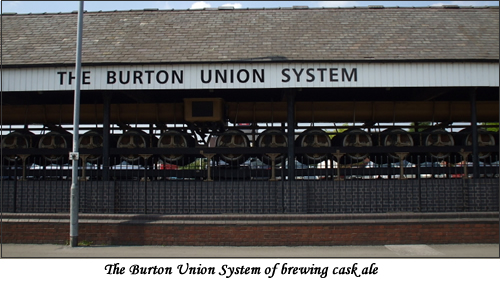

Every brewery employed coopers to make the barrels (or ‘casks’) for the beer and this job required an apprenticeship of 4 years.

To make a cask, flat boards were cut into staves and each was worked until it felt, with experience, that it was ‘right’. The staves were then bent into a bulging shape by heat or steam. Many breweries, including Bass had a steam cooperage. Heavy iron hoops called truss hoops were fitted to hold the cask together.

Marston’s brewery in Burton still employs a cooper as it uses the Burton Union System for brewing its Marston’s Pedigree Bitter. This is a re-circulating fermentation system, whereby a row of casks is connected to a common trough by a series of pipes.

Brewer’s labourers stacked the full casks ready for transportation and this was known as ‘stowing’. As the casks were large, it was hard and heavy work. Casks were pushed up wooden ramps with wooden bars and stacked one on top of the other. This is now done on pallets by a forklift truck.

My father in law used to stow in his early days at Bass. He has told me that he burned up so many calories in a day that he used to take an entire loaf of bread for his sandwiches.

All workers were allowed to drink the beer, as they had to replace the fluid lost. My father in law said that he drank up to 30 pints a day, but didn’t feel drunk because he worked it straight off. Historically, Beer was much safer to drink then water, as the water used in its production was boiled during the process.

This allowance of beer still continues to this day with workers getting coupons for company products. In the past they were also given their allowance in bottled beer to take home.

It was the drayman who delivered the beer to the pubs. The casks (or in more modern times, the metal kegs) were dropped into the pub cellar through the cellar flaps that mostly opened up onto the street outside. These days most pubs have lifts in them for health and safety reasons, but up until a few years ago, the kegs were dropped into the cellar by either ‘roping’ (the lowering of the keg by the drayman at the top to his mate in the cellar below), or just dropping them onto a ‘pig bag’. These were sacks filled with corks to cushion the fall and had to be positioned in the correct place so that the keg would land on them.

My husband was a drayman and was in the cellar when his mate dropped a keg onto a ‘pig bag’ which he should have, in fact, ‘roped’. The keg missed the bag and jumped 10 foot into the air, hitting and smashing a sink, resulting in water flooding the cellar, bouncing out again and disturbing and shaking up the contents of the landlords other kegs, so that he had to leave them for a week to settle. I bet they didn’t get a pint in there again!

The breweries also employed wheelwrights joiners, painters, engineers, chemists, watchmen etc. They also had their own fire brigades, and Bass and Allsopps’ would turn out to help the local fire service if required. Horse drawn engines were used in the days before motor transport, as the photograph opposite shows.

SOURCES

Burton on Trent, its history, its waters and its breweries by William Molyneux (1869)

Where beards wag by George Ewart Evans

History of Burton upon Trent Part 1 by Denis Stuart

Margaret’s father in law and her husband’s personal memories of working in the brewery and transport departments at Bass from 1946 to 2000.

The Brewing Process

|  |  |

Mashing

The malt is crushed so that the grain kernels break apart and separate. The resulting grist is mixed with heated water in a vat called a ‘mash tun’ and brought to and rested at a set temperature, so that the enzymes in the malt liquify the grain and convert the starch to sugar (typically maltose) and carbohydrates. The mashing process takes around 1-2 hours.

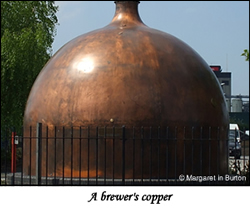

Boiling

The mixture is then filtered to remove the grain kernels, in a process known as ‘lautering’. The remaining amber coloured liquid (or ‘wort’), is transferred to a copper for boiling, when hops are added to contribute towards the bitterness, aroma and flavour. The boiling process serves to terminate enzymatic processes, precipitate proteins and isomerise hop resins, as well as concentrating and sterilising the wort. The boiling part of the process lasts between 50 and 120 minutes.

Fermentation

After boiling, the mixture is cooled and moved to a fermentation vessel. Yeast is added which converts the sugars in the malt to alcohol, carbon dioxide and other components through a process called ‘glycolysis’. This takes 1 to 3 weeks.

Aging

Some breweries ferment the beer again, but after this it’s stored in storage tanks for several weeks or months to improve the flavour.

Finishing

The stored beer is filtered again before it is put in casks or kegs, bottles or cans. Nowadays it is also pasteurised.

SOURCES

The Coors Visitor Centre, Burton upon Trent

Breweries in Burton in 1888

Samuel Allsopp and Sons

Bass, Ratcliffe and Gretton

J Bell

T Bindley

H Boddington

J and T Bowler

Burton Brewery

Carter and Scattergood

Charrington

W and G.R. Clarkson

Clayton

T Cooper

Dawson

Everard

James Eadie

S Evershed

F Heap

C Hill and Son

Ind Coope

Mann, Crossman and Pauline

John Marston

J Nunnerley

J Porter and Son

T Robinson

T F Salt

Sykes

F Thompson and Son

Truman, Hanbury and Buxton

A B Walker

Peter Walker

Worthington

J Yeomans

Cask sizes

Pin ~ 4 and a half gallons

Firkin ~ 9 gallons

Kilderkin ~ 18 gallons

Barrel~ 36 gallons

Hogs Head ~ 54 gallons

Butt ~ 108 gallons