The production, serving and consumption of beer is a very important factor in the lives of all our ancestors, not only from its use as a safe alternative to water but because so many of them were involved in its production.

Many farmers were also listed in census returns as brewers and how many of us have found an ancestor listed as a publican or barmaid?

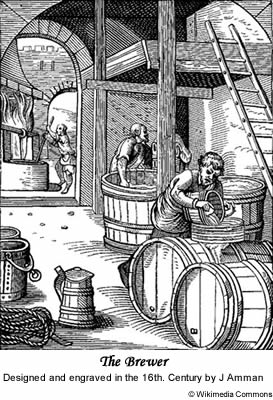

Brewing

“It is you who pour out the filtered beer of the collector vat; it is like the onrush of the Tigris and the Euphrates. Ninkasi, it is you who pour out the filtered beer of the collector vat; it is like the onrush of the Tigris and the Euphrates”

Black, J.A., Cunningham, G., Fluckiger-Hawker, E, Robson, E., and Zólyomi, G., The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature (The ETCSL Project), Oxford 1998.

These are the last two lines of the Sumerian poem ‘A Hymn to Ninkasi’. Ninkasi was the Ancient Sumerian goddess of brewing. It was written in the 19th century BC and contains the oldest recipe for beer that exists, but the actual brewing of beer has been traced back to 4000 BC in Mesopotamia. Since then beer has popped up everywhere, in the tombs of Egyptian Pharaohs, where it was considered a medicine, and in the bronze bowls of King Midas in Turkey, where it was enjoyed with a meal of spicy mutton. It first appeared in Britain probably around 3000 BC with the arrival of barley from the Near East.

These early beers, were in fact ales, as they did not contain hops until the 16th century. Their alcohol content was low, herbs and spices were added to improve their flavour and they did not keep well. Our word beer comes from the Old English for barley, which was the preferred grain of the brewers.

In medieval times beer was the universal drink of old and young alike. Water was known to make you sick and milk was only thought suitable for the ill or young. That only left beer and it was drunk in vast quantities. The necessity of always having beer on hand to slake one’s family’s thirst meant that the would be medieval domestic goddess not only had to bake the family bread, make the family clothes starting at the wool spinning stage, but also to brew the family beer. It was such a simple process that it could be done in any home no matter how grand or lowly as long as there was a bright fire and a good supply of barley.

To make ale, the grain had first to be malted, which involved dampening it and leaving it in a warm place to germinate. Once the grain had sprouted it was roasted to stop the germination process. This malted grain was then added to boiling water (this is what made the ale safe to drink, unlike plain water, but it was a long time before anyone would recognize the significance of this) and herbs and spices were mixed in for flavour. When hops were introduced they were added at this point in the process and the result was beer. Finally the liquid was placed in barrels and yeast added for fermentation. The addition of hops increased the strength of the beer and also allowed the malted barley to be used three times to make firstly, a very strong beer, secondly a slightly less strong beer and finally what was known as small beer, which was the everyday drink of the family, the other two being kept for special occasions.

“The roots and herbs beaten and put into new ale or beer and daily drunk, cleareth, strengthen and quicken the sight of the eyes”

Nicholas Culpepper

Brewing was largely women’s business, except in the monasteries where the monks brewed beer for themselves and their pilgrim visitors ensuring a regular income for the order. When formal licensing for alehouses was introduced in the middle of the 16th century they were often issued to widows, as brewing was one of the few respectable ways for them to make money. In fact many families sold their surplus production to supplement their incomes. Licensing had probably already existed on a local scale for some time before the 1552 act, but with a perceived rise in the level or drunkenness and the disorderly behaviour that went with it, a national law was felt necessary.

Standards for the quantity, quality and pricing of ale were already controlled by a 13th century statute called the ‘Assize of Bread and Ale’. This saw men called ale-conners visiting alehouses, tasting the ale, checking the measures and making sure the prices corresponded to the set price based on the price of cereals. This set pricing was later abandoned in the 15th century for being too cumbersome and unjust. If the ale-conners found fault with the alehouse they could report the owner to the court-leet, the forerunner of the magistrate’s court, where fines and punishments were meted out.

Alehouses, Taverns and Inns

By the 19th century there were three established places for ale and beer to be bought and sold. The first were the alehouses, which brewed on the premises, the second were taverns that sold wine and food as well as beer and ale, and the third were inns, which provided accommodation.

Inns had seen their beginnings in the monastery dormitories welcoming the first pilgrims. After the murder of Thomas à Beckett in Canterbury Cathedral in 1179, the number of pilgrims on the road rose and the monasteries had trouble catering for their numbers. Separate inns were established, often by the monks themselves, although their involvement in them did not last. Some of these inns with religious links survived for a very long time. Chaucer has his pilgrims in the Canterbury Tales start their pilgrimage from the Tabard Inn in Southwark. The Tabard stood on the same spot from at least the time of Chaucer’s writing in 1388 until it was demolished in 1874.

From the 1660s onwards the number of regular stagecoach services increased. The arrival of turnpikes and tolls helped to speed up journeys and make them more reliable, however stagecoach travel was still a slow business. In 1734 the journey from London to Edinburgh along the Great North Road took ten days. The travellers needed somewhere to rest and eat during the journey and the coaches needed new horses, as a result inns flourished and soon became essential to the local community as they hosted churchwarden meetings, inquests, auctions and even the magistrate’s court when it was in the area. They often housed the army too, as barracks didn’t become the norm until the 19th century. The arrival of the railways announced their decline and hotels took their place near train stations. A neighbour of Chaucer’s Tabard Inn, The George, only avoided complete destruction when the railway arrived, because the Great Northern Railway decided to use it as a depot.

“When I reached Knowlesbury the inn was shut up, and bills were posted on the walls. The speculation had been a bad one, as I was informed, ever since the time of the railway. The new hotel at the station had gradually absorbed the business, and the old inn…had been closed about two months since”

The Woman in White, Wilkie Collins

Taverns, selling only wine and serving good food, developed alongside towns from Elizabethan times onwards reaching their greatest popularity in the 18th century. They were more upmarket than the alehouses and provided a comfortable and relaxing atmosphere for the new urban professionals, lawyers, writers and bankers, to meet, drink and discuss the issues of the day. The City of London was particularly well known for its taverns some of which are still standing today. Along with coffee houses, taverns became meeting places for various clubs and political groups such as the Kit-Cat club, which met in Christopher Cat’s tavern in Gray’s Inn lane. At the time of the Kit-Cat club, drinking a lot and sometimes to excess in public was not frowned upon, but as this became less acceptable the tavern lost its appeal for the comfortable chatting classes and they moved on to private gentlemen’s clubs. Alehouses also had their hand in the decline of the tavern as they became larger and more comfortable, and started offering food.

The alehouse began to be known as a ‘Public House’ during the 18th century. From humble beginnings in the brewer’s front room they grew into larger establishments with, in some cases, several parlours and a bar and eventually became purpose built in the 19th century. Home brewing was now in decline, it required space and time, which life in the newly industrialised towns did not easily afford. Victorian town planners recognized the growing importance of public houses and made sure every new street of houses built was in easy walking and spending distance of a pub. For the builder licensee, making sure the pub was the first building completed ensured extra earnings for him, as his labourers ploughed back their hard won wages into his business. The working classes had nowhere to meet and pubs fulfilled this need.

Involvement in trade unions and politics for the working classes was frowned upon by the middle and upper classes. Pubs provided private rooms for the payment of union subscriptions and meetings as long as drink was consumed at the same time. Other clubs also saw their beginnings in the fug filled beery atmosphere of the local; such as choirs, gardening societies and a whole host of sporting clubs.

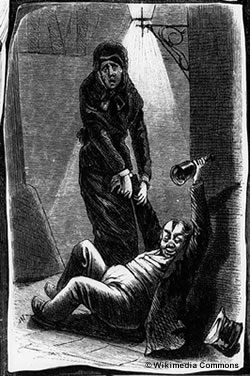

Increased urbanisation and the proliferation of public houses in the working class districts meant that more regulations were needed to control drinking. At the beginning of the 19th century there were no laws regulating opening hours and no lower age limit for purchasing alcohol. In 1839 the Metropolitan Police Act banned Sunday opening in the capital, which gradually spread to the rest of the country becoming the norm by 1848, and introduced fines for drunken behaviour. This same act also set a minimum age of 16 for drinking beer on licensed premises, but a ban on selling alcohol to under 14s only came into being in 1901. The first off licences had started to appear early in the century as a result of cheaper bottled beers becoming more readily available. Comic scenes involving drunks brought before the magistrate became standard fodder for the writers of the time.

“…how the said Thomas Potter had feloniously obtained possession of five door-knockers, two bell-handles, and a bonnet: how Robert Smithers, his friend, had sworn at least forty pounds’ worth of oaths, at the rate of five shillings apiece, terrified whole streets full of Her Majesty’s subjects with awful shrieks and alarms of fire; destroyed the uniforms of five policemen, and committed various other atrocities, too numerous to recapitulate. And the magistrate, after an appropriate reprimand, fined Mr. Thomas Potter and Mr. Robert Smithers five shillings each, for being, what the law vulgarly terms, drunk, with the trifling addition of thirty-four pounds for seventeen assaults at forty shillings a-head”

Charles Dickens ‘Sketches by Boz’

For a certain portion of the population, the excessive consumption of alcohol largely due to cheap prices in the gin palaces and pubs, was a growing problem. Unhealthy practices had become the norm; pubs were used as pay offices for workers, in particular, as we have already seen, in the building trade. In the potteries, wages were paid in large notes that had to be changed at the public house, allowing a certain amount to be creamed off in the process. Some people were even paid a part of their salary in beer. All of this lead to a large proportion of an already small salary disappearing on pay day down the throats of the workers. Life was very difficult for the workers’ families:-

“My husband”, said the first woman, “works under a publican, and I know that he earns now 12s. or 13s. a week, but he brings home to me only half-a-crown, and sometimes not that much. He spends all the rest at the public-house, where he gets his jobs; and often comes home drunk”

The Morning Chronicle : Labour and the Poor, 1849-50; Henry Mayhew – Letter XXIV

Payment of wages in public houses was made illegal in 1883, but testimonies of this kind helped to fuel a growing movement, which became particularly popular among nonconformists, that of temperance.

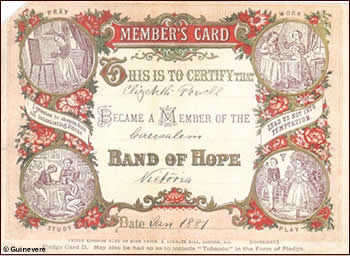

The Temperance Movement

In 1832 in Preston, Joseph Livesey, a nonconformist, founded his Temperance Movement. He had noticed from his travels around Preston visiting the poor that one of the main causes of all the distress he witnessed was drink. Moderation was already being advocated as a possible way forward, but Joseph took this one step further by demanding complete abstinence and by inciting his followers to sign a pledge, calling those who signed up “the great army of temperance”.

More followers soon joined the movement and the ‘British Association for the Promotion of Temperance’ was established in 1835. In 1847 in Leeds, an association was formed for working class children called ‘The Band of Hope’. There were weekly meetings where children from the age of six learnt about the demon drink and were encouraged to sign the pledge. They also went on outings organised by the different temperance associations.

Thomas Cook started on a long career in tourism when he negotiated special rates on the railway to take his temperance group on a trip in 1841. From there he extended his tours around England, and in 1851 he decided to organise a trip to the ‘Great Exhibition’, which was not only educational, but was also an alcohol free zone, a win-win situation for a temperance group.

The movement continued to grow and was influential in the regulation of opening hours. By 1900 about one tenth of the adult population abstained from alcohol. Of course, once they had signed the pledge the new members would no longer feel comfortable in a traditional pub but, fortunately for them, temperance bars opened in the 1830s and flourished throughout the rest of the century.

Temperance bar owners were often herbalists and chemists, and they used their knowledge of plants to concoct their delicious and healthy drinks, such as dandelion and burdock and ginger beer.

Temperance bars died out as the temperance movement itself faded after the failure of prohibition in America in the 1920s. The arrival of industrialised fizzy drinks after the Second World War sounded their death knell. Just one temperance bar remains, Fitzpatricks, in Rawtenstall, Lancashire.

Georgette

© Georgette 2008

SOURCES and FURTHER READING

The Victorian Public House ~ Richard Thames

Consuming Passions ~ Judith Flanders

The Tudor Housewife ~ Alison Sim

Real Ale and Beer ~ A brief History, Traditional and Historic London Pub Guide

Dictionary of Victorian London

Temperance Society

The Brewery History Society

Pub History

Pub History Society