On 14th February, St. Valentine’s Day, lovers all over the world exchange heartfelt sentiments to express their feelings for one another, whilst others send anonymous greetings to the ‘objects of their desires’.

Whilst researching this article I have tried to uncover the origins of St. Valentine’s Day, only to discover that its history is not entirely clear. There were several Christian martyrs by the name of ‘Valentine’ in the days of ancient Rome. None had any particular romantic connections, although one was indeed remembered on 14th February. Of course this didn’t deter the literary world, as fiction soon become accepted as fact. One of the first references to St. Valentine’s Day being connected to romantic love was Chaucer’s poem of 1382, ‘Parlement of Foules’, in which he wrote:-

For this was on seynt Volantynys day

Whan euery bryd comyth there to chese his make

Even the great bard himself, William Shakespeare, got in on the act, mentioning the ‘tradition’ in his play ‘Hamlet’:-

To-morrow is Saint Valentine’s day,

All in the morning betime,

And I a maid at your window,

To be your Valentine.

Then up he rose, and donn’d his clothes,

And dupp’d the chamber-door;

Let in the maid, that out a maid

Never departed more.

It was the Victorians, however, who saw the commercial benefits of celebrating St. Valentine’s Day. The greetings card business had started primarily with the very first Christmas card designed by John Callcott Horsley in 1843. Aided by the technological advances in the printing process, the production of greetings cards became big business, and those celebrating St. Valentine’s Day were by no means an exception.

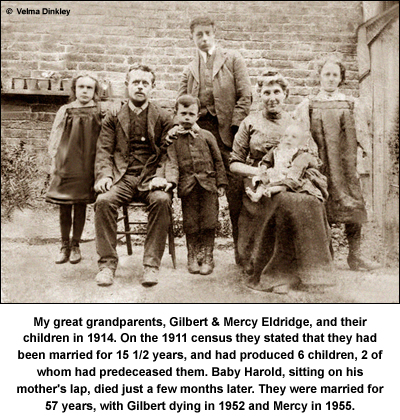

It’s difficult to imagine the personal lives of ancestors when we see them as a collection of names and dates, but they were human beings too, just like us. Even though their world was so different and their lives so much harder, they still fell in love and suffered heartbreak, just like we do now. With disease rife and life expectancy so much lower, it would appear that they remarried with apparent ease. However, without a spouse, a woman had no means of financial support and a man had no-one to look after his home and children. So our ancestors did not always marry for love, but for necessity. With divorce impossible for the vast majority of people until the 20th century, marriage was for life… for better and for worse.

The work of reformers, the protests of the suffragettes and women’s efforts in World War One cleared the path to emancipation, leading to the right to vote and eventually, equal rights, although it was a long battle. Historically, women, their property, income, chattels and children were the property of their husbands and they had few legal rights. While it was the husband’s legal responsibility to protect his wife, she had to obey him and, with no contraception, spent her fertile years childbearing. It’s not uncommon to discover families with well over 10 children, despite the fact that they lived in abject poverty. I have discovered one couple who produced 16 children, over a 22 year period, although they suffered the heartbreak of five predeceasing them.

With childhood diseases rife and often fatal, and without a vaccination programme and clean sanitary conditions as we know today, childhood mortality was particularly high, with babies having a one in three chance of reaching their first birthday. Even though burying your own offspring was commonplace, it was still a heartbreaking experience which many couples had to bear.

Unless we have any evidence of our ancestors exchanging romantic sentiments on February 14th, then we will never know whether they did indeed celebrate St. Valentine’s Day. I’m inclined to think that my working class ancestors spared little thought to such frivolities. The popularity of this annual event emphasises the fact that our lives are so much easier than that of our forebears. We may well be in the middle of an economic recession, but still millions of pounds will be spent this year just to say three simple words… “I love you”.

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2010

Sources and Further Reading

Women in England 1760-1914 A Social History by Susie Steinbach. ISBN 0753819899