The Salish people had lived in what is now south east British Columbia hundreds of years before the first European explorers arrived. The Spaniards were the first Europeans to visit and, by way of the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, claimed the west coast of North America. Cook also passed through in 1778.

Captain George Vancouver, who had served with Cook on his travels, arrived in the Pacific Northwest in 1792 and met with the Spanish captains Valdez and Galiano, and one of Vancouver’s best beaches, Spanish Banks, is named for the meeting place. Vancouver briefly landed at what is now Point Grey and managed to sail through the First Narrows into the waters of the inner harbour, which he named Burrard’s Channel. He also named various other locations (e.g., Point Grey, Puget Sound, Gulf of Georgia) and noted that the shores of the inlet were, “well covered with trees of a large growth, principally of the pine tribe”.

In 1801, the first Europeans arrived overland. They were a party led by Simon Fraser of the North West Company, arriving via a river which was later named after him. The Hudson Bay Company (HBC), one of the oldest companies in the world (it was granted a charter by Charles II in 1670), merged with the NW Company in 1821 and built the first non native settlement in the area, a trading post on the Fraser River in 1827 called Fort Langley. Fur became the main trading commodity with over 2,000 beaver pelts being shipped out in 1832. Soon, salmon also became a major export. At this time, the HBC had a virtual monopoly on all trade in the Pacific Northwest. In 1839, Fort Langley moved to its present site, 35 kilometres upstream.

The Fraser Valley gold rush in 1858 brought 25,000 men to the area, mainly from California, prompting the governor of the British colony of Vancouver Island, James Douglas, to declare the mainland a British colony too, as he was fearful that the Americans might claim the area for themselves. A small contingent of Royal Engineers also arrived in 1858 ‘to show the flag’ under the command of Colonel Richard Moody, who became an important figure in British Columbia history. It was Moody who chose the site of the first large settlement in the Lower Mainland, Queensborough, later to become New Westminster, the new name being chosen by Queen Victoria herself.

In 1859, coal was discovered in Burrard Inlet, but was found to be of poor quality. However, the area was named Coal Harbour, a name which is still retained today. The same year, Moody had a road built from New Westminster through to the Burrard Inlet. 1860 saw the first important law concerning land and several claims were staked in what is now the City of Vancouver. The ‘Three Greenhorns’ – John Morton, William Hailstone and Sam Brighouse, put in a sizable land claim in the West End area of Vancouver. John Morton had been raised in a family of potters and had plans to start a brickyard. The business failed but these three gentlemen, together with Samuel and Fitzgerald McLeery, were the first settlers in what is now Vancouver. The McLeery’s uncle, Hugh McRoberts, an Irishman who had originally emigrated to Australia, arrived in British Columbia after the death of his wife, and after spending some time in Yale and New Westminster, he settled on Sea Island. Late in September 1862, he transferred lots of land which he had claimed on the north bank of the Fraser River to each of his two nephews. Part of the property was continually inhabited by the McLeery family until 1955 when it was sold to the City of Vancouver, which demolished it in 1956.

The first lumber mill, Pioneer Mills, was built on the North Shore of Burrard Inlet in late 1863. The forests around Vancouver provided “lumber of the finest quality”, and the first exports took place in 1864 with shipments going to Valparaiso and Australia. Stamp’s Mill became the first industry on the Vancouver side of the Inlet. After Edward Stamp left, the name was changed to Hastings Mill.

In September 1867, a new character appeared – ‘Gassy Jack’ Deighton (born in Yorkshire) arrived from New Westminster to open the first bar close to the Hastings Mill, in the area which still retains his name, Gastown. He was so named because of his garrulous nature. He arrived with his native wife, her niece, some furniture and very little money but persuaded the local sawmill workers to build the bar “in exchange for all the whisky they could drink at one sitting”. Before Gassy Jack appeared on the scene, the nearest bar was 20 kilometres away so the workers were more than happy to help and the Globe Saloon was up within 24 hours. An old-timer, Harold Ridley, described the building in 1933 as, “a bit of a shack about 12 feet wide by 20 feet long, with board and batten sides, and a roof with a pitch of about forty degrees, covered with hand-split cedar shakes. There was no chimney but a stove pipe stuck out of one side”. The saloon was so popular that a community grew up around it and in 1870, Gastown was incorporated as the town of Granville.

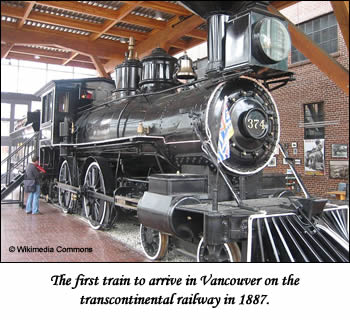

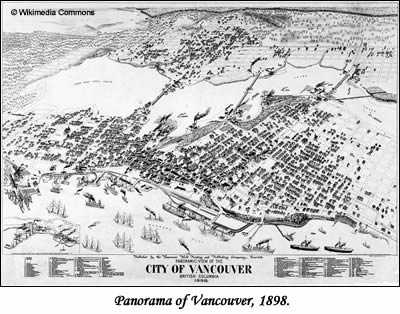

In 1871, British Columbia became part of Canada, and the promise of a transcontinental railway was born. The first transcontinental train arrived in nearby Port Moody in 1886, in the presence of the head of the Canadian Pacific Railway (‘CPR’), William Van Horne. Some say it was he who decided that the name of the new city at the proposed terminus should be Vancouver after Captain George Vancouver, rather than Granville. The City of Vancouver was incorporated the same year and expanded rapidly – there were then about 1,000 residents. In July 1886, a brush fire burnt the city to the ground (by some reports, within 45 minutes the city was gone), but buildings were quickly replace this time of brick. The CPR’s first train arrived in Vancouver’s Coal Harbour in 1887; the final stop of the first transcontinental trip.

To ensure continued growth, new industries were required and these were encouraged by the city government. In 1890, an American investor, Benjamin Rogers, asked the city for various concessions in order to build a sugar refinery. This proved to be very successful, and much of the product was sent via the CPR to eastern Canada. Shipping also stimulated local business.

By the time of the 1891 census, the population had grown to almost 14,000; however 60% of the population were male and the vast majority of them were of Canadian and European descent. The exception was the Chinese, some of whom had arrived at the time of the gold rush. Also, over 6,000 had been brought in from China and employed as cheap labour to work on the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway. Discrimination was rife and the city itself refused to hire them, or permit them to work on any city-assisted project. They were also subject to a head tax of $50, which was meant to discourage them from bringing over family members. By 1903, the head tax was $500 per individual, which was the equivalent of two years’ wages at the time. The head tax was ended by the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which stopped Chinese immigration altogether, with a few exceptions. This remained in effect until 1947. Today, Vancouver’s Chinatown is a popular tourist attraction and it is still located at the site of the settlement of the original Chinese community.

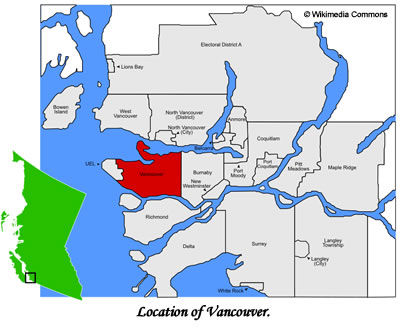

Over the next few years, other municipalities came into being – North Vancouver, South Vancouver, Burnaby, Coquitlam. In 1912, West Vancouver with a population of about 700, was incorporated. It was popular as a vacation spot and an enterprising John Lawson had started a ferry service in 1909 to provide access.

The city was booming, more families arrived; the first public transit tram had started in 1891. The Vancouver Reading Room was established in 1889 and a museum was opened in 1894. The city took advantage of the Klondike gold rush by advertising itself in Canadian, American, and European newspapers and by the end of 1897 “every hotel in Vancouver and every boarding house” was full of prospectors preparing to travel to the Klondike.

The nine p.m. gun was established at Brockton Point in Stanley Park in 1898, a tradition which continues to this day. By 1900, the population had exceeded that of the provincial capital, Victoria. The lumber industry continued to grow and, along with fishing, continued to dominate. In addition, imported goods such as tea, spices, coffee, etc., were processed and packaged before being transported by railway to other areas of Canada. The Board of Trade worked tirelessly to promote the city. By 1907, it was reported that, “the city was growing by 50 people per day”.

The University of British Columbia opened in 1915 with just a few students, and the same year, the new CPR railroad station was opened at the foot of Granville Street. An industrial area called Granville Island was created by piling the soil dredged out of False Creek – today it has a thriving market, artisan shops, office , houseboats and many marinas. By 1920, Vancouver was bigger than Winnipeg. Houdini attracted a large audience when he suspended himself from the Sun Tower that same year. In 1928, the communities of South Vancouver and Point Grey decided to amalgamate with Vancouver, making it the third largest community in Canada.

The first bridge to link the city to the North Shore, the Second Narrows bridge, was completed in 1925. In 1937, the Guinness family, which owned considerable property in West Vancouver, financed the building of the Lion’s Gate Bridge over the ‘First Narrows’ to encourage people to settle there in what is still known as British Properties. The bridge was officially opened by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth in May 1939. Tolls were 25 cents per car. The family eventually sold the bridge to the Province in 1955 and tolls were dropped in 1963.

Through the succeeding decades, Vancouver and the Lower Mainland municipalities continued to grow. During WWII, the local shipyards built ships for the navy and Boeing employed over 5,000 at its factory producing parts for the B-59. The Japanese Canadians were all removed to internment camps – they received very little compensation for their property which was ‘taken into custody’. In 1958, the original Second Narrows was replaced, but during its building, 19 men were killed when part of the bridge collapsed. It is now known as the ‘Iron Workers’ Memorial Bridge’. The 1960s saw a visit from the Beatles, the opening of the Grouse Mountain Skyride and Whistler’s first ski lifts. In 1961, the population of metropolitan Vancouver had reached over 800,000.

The City of Vancouver celebrated its 100th birthday in 1986 by opening its doors to the world at Expo 86; over 21 million visitors attended. The same year, Skytrain opened.

Today, with inhabitants from all over the world, the population of the metropolitan area exceeds 2.1 million. It has been ranked highly as ‘the most liveable city’ in the world for over a decade. With its natural beauty, the coastal mountains, the sea and its temperate climate, tourism is now one of the area’s largest industries. There aren’t many places in the world where you can ski, sail and play tennis all on the same day…

Vancouver and Whistler look forward to being on the world stage and welcoming the world to the 2010 Winter Olympics.

jenoco

© jenoco 2010

SOURCES

Vancouver, the Pioneer Years 1774 – 1886 by Derek Pethick

Vancouver, An Illustrated History by Patricia E. Roy