In November 1st, 1943, the inhabitants of the tiny village of Imber on Salisbury Plain were called to a meeting in the schoolroom and given 47 days notice to leave their village – they thought the meeting would be about the installation of piped water. On November 27th, 1943, the last wedding took place at St. Giles Church between Bernard Wright and Phyllis Daniels.

The village of Imber was needed as a place for the American army to practise prior to the D-Day landings. The villagers all left by December 17, 1943 (most voluntarily, some forcibly) with the expectation of returning after the war. The village blacksmith was reported to have been found sobbing over his anvil – he was the first man to die after the eviction and was taken back to Imber for his burial.

Little Imber on the Downe,

Seven miles from any Towne,

Sheep bleats the unly sound,

Life twer sweet with ne’er a vrown,

Oh let us bide on Imber Downe.

The War Office had started to buy up land on Salisbury Plain close to Imber towards the end of the 19th century, and had begun to use it for army manoeuvres. By 1902, it owned 47,000 acres. At the time of the depression in the late 1920s, when times were particularly hard, the army offered good prices for the farms and even the land on which the village sat was purchased. Few people were put off by the tenancy conditions, which included allowing the War Office to take control and also evict residents. By the start of World War II, most of the land was owned by the War Office.

At the end of the war, efforts were made by the displaced villagers to return to Imber. Many were convinced that the promise had been made that they would be allowed back and even that a letter had been sent to the residents indicating this, although none has come to light. For his book ‘Little Imber on the Down’, Rex Sawyer interviewed several old residents. One was Ellen Carter, sister in law to my great grandmother and postmistress at Imber for 34 years, who said she was told by officers in charge that they were being moved for their own safety and would be allowed back as soon as possible.

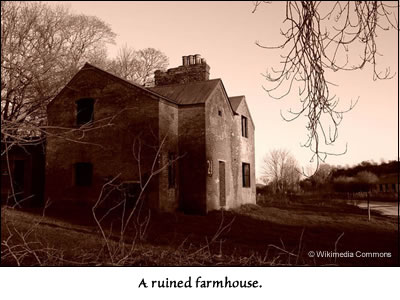

In 1947, the War Office issued a statement indicating that, although the village itself had not been used for training, it had suffered accidental damage and neglect and would be very costly to reinstate. Also, permitting the villagers to return would greatly restrict the army’s ability to carry out modern forms of training. At this point, the army allowed street-fighting to take place, further destroying the buildings. The church and graveyard were however, ‘out of bounds’ for the training exercises. The Baptist chapel, which had originally been fenced off, had already been partially ransacked. It was eventually demolished as it was considered unsafe.

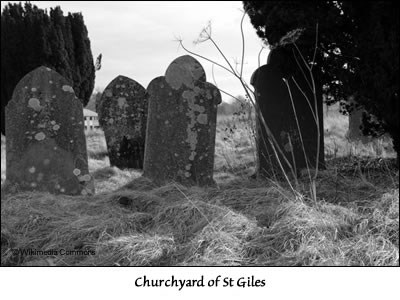

Occasionally, groups were allowed to visit the village and to attend church services and funerals. By 1960, church services were held annually on the Saturday in September closest to St. Giles’ Day. It was in that year that it was proposed that the church be moved to Warminster but this was met with great resistance by the villagers. In 1961, Amesbury Rural District Council decided to object to a draft order issued by the Ministry of Transport to close the roads and other rights of way around Imber permanently.

Over 2,000 attended a rally demanding that the villagers be allowed to move back, but a subsequent public enquiry found in favour of the Ministry of Defence and military use was allowed to continue. However, it was decided that the church would be maintained and continue to be open for worship on the Saturday closest to St. Giles’ Day. At the present time, Imber is open up to 50 days a year. The ancient church, which was struck by lightning in 2003, has been taken over by the Churches Conservation Trust, allowing funds to be made available for the much needed restoration which is currently taking place.

One of my maternal great grandmothers, Eliza Carter, was born in Imber in 1863 – my earliest known ancestor from this isolated village on Salisbury Plain is John Daniel, a tailor, who was born circa 1649. My other maternal great grandmother also had a connection to the village in that her sister, Annie, married Imber native Frank Wyatt (also a relation through his grandfather). My great uncle recalled how Frank used to go up on the Plain after the villagers had been forced to leave, look over towards Imber and ‘just wish he could go home’.

Imber, situated in a secluded valley six or seven miles from Warminster, was recorded in the Domesday Book, when it is b elieved it had a population of about 50, but, before that, it was probably part of the Abbess of Romsey’s estate at Edington, which was established around 967. The church of St. Giles, which is a Grade I listed building, dates back to the 13th century and has 15th century wall murals and the oldest and most complete bell ringing charts in the country (1692).

elieved it had a population of about 50, but, before that, it was probably part of the Abbess of Romsey’s estate at Edington, which was established around 967. The church of St. Giles, which is a Grade I listed building, dates back to the 13th century and has 15th century wall murals and the oldest and most complete bell ringing charts in the country (1692).

From records, it is known that the population of the village had risen to about 250 by the 14th century. At this time also, part of the village had been granted to John de Rous. Two stone effigies relating to him, and previously in St. Giles Church, Imber can now be found in nearby Edington. In 1709, John Sanders wrote of a visit to the Wadman family of Imber and the “two noble antient monuments (in the church) lying cross legged like Knights Templar, under each is a stone sepulchre with ye bones of a body in each of them”. The Wadmans of Tinhead Court in Edington rebuilt Imber Court and were an important family in the village, also helping out the poor of the parish.

Most of the population were involved in agriculture or occupations that depended on it and in 1800 there were approximately 50 cottages. Industrialisation and the Poor Law changed Imber, as did the agricultural decline later in the century – the young left the village for better jobs elsewhere and the pauper elderly were sent to Warminster Union to spend the remainder of their days. The track between Imber and Warminster was often impassable during the winter, which further isolated them from family. The stream known as the Imber Dock ran through the main street making the village vulnerable to frequent flooding, but lack of water was also a problem in the summer. There are records of instances of bad flooding where buildings collapsed and villagers perished.

|  |

After a peak of 440 in 1851, the population of the village gradually declined until only about 150 remained at the time of the take-over. In 1851, there were five farms, a pub (The Bell), a Baptist chapel, smithy and windmill, as well as Imber Court, St. Giles Church and the ordinary cottages. Probably because of its size, Imber was a close knit community.

One of my great aunts, grew up in Imber at the turn of the century. In an interview she gave, she remembered her childhood. Her father was the village carpenter and wheelwright, her uncle the baker, her grandfather the blacksmith and her mother the church organist. There was no village shop and all the main necessities of life were produced and shared among the villagers. The carrier used to make the difficult journey to Warminster once a week, thus enabling the villagers to make contact with the outside world. She left in 1914, at the age of 16, to work in London. She must have been completely overwhelmed after the quietness of Salisbury Plain!

|  |

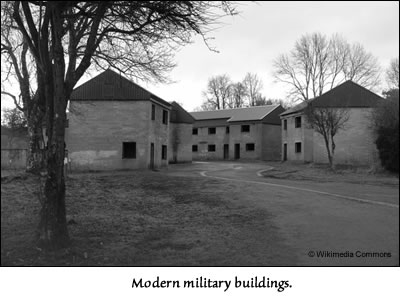

Today, little remains of the village of Imber, except the church. The army has built its own structures where once the cottages stood – square two storied buildings – the cottage gardens no longer exist and there is apparently an abundance of barbed wire. Visitors to Imber must make sure they do not stray from designated areas for fear of encountering unexploded shells. None of the displaced villagers remain, but some of their relatives and descendants still make the journey to attend the church service every year in their memory.

jenoco

© jenoco 2009

SOURCES

Little Imber on the Down by Rex Sawyer

Memories of Imber by Ivy Carter

Gloucestershire Notes and Queries edited by Rev. Beaver H. Blacker in 1884, quoting from a manuscript of John Sanders, 1712

Imber – The Town That Got Conscripted

Wiltshire Magazine April 2009, p 28-29