In stark contrast to one of my families, who lived for generations in the same small village in Wiltshire, my husband’s Scottish paternal line seems to have been born with itchy feet. Peter McKinlay emerged from Callander in Perthshire trailing a very scanty family history behind him.

He was born on 27th May 1780 and presented for baptism the following day by his parents, Finlay McKinlay and Janet McFarlane. The record also tells us that the little family was ‘of Tombea’ – a small village near Callander. Rob Roy McGregor operated in the region in the early 1700s and perhaps this is why a story persisted down through the generations that a McKinlay wife set about Rob Roy’s men with a broom when they attempted to steal a cow from her family.

The McKinlay Family Tree (The tree will open in a new window.)

Peter appeared in Campsie, Stirlingshire, some time before 1804, marrying Margaret Kincaid (a very common family name near Lennoxtown). He supported a rapidly increasing family, following his trade as a slater. Worn out by her exertions, Margaret Kincaid died in 1827, seven years after the birth of the youngest child, John. Three years later, Peter remarried, this time to Jean Stewart, also from Callander Perthshire. His family grew up and dispersed, and by 1841 there was only John living with his father and stepmother in Campsie, learning his father’s trade as a slater.

Mary McDougall, also possessed of a mysterious past, was living in Campsie. She was the daughter of a fisherman named Archibald McDougall and his wife Isabella Livingstone. Isabella had made her only public appearance on the birth record of her second daughter Elizabeth in Burntisland, Fife. Mary claimed also to have been born in Burntisland, but I have found no trace of her birth or, indeed, of her parents’ marriage. Mary wed John McKinlay in Campsie in 1843 after the proclamation of banns.

Three children were born in Campsie, but by 1850, John and Mary had moved with the two surviving children, Peter and Archibald, (leaving the wee first-born, Isabella, behind in the graveyard in Campsie) to Main Street in Anderston, Glasgow. This was a rapidly developing industrial area close to the docks on the River Clyde. There was a high demand for working class housing and perhaps the building boom provided work opportunities for John, who had already been obliged to alternate his trade as a slater with dealing in spirits in Campsie. John’s father, Peter, was left behind in Campsie, where he descended into pauper status by 1851, with two lodgers in the house.

The same census taken in Glasgow shows that John was once more dealing in spirits, had a servant girl, but had lost the eldest son, Peter. However, the family fortunes seem to prosper from that point, as a replacement Peter was born in 1852, both grandfathers arriving to ‘wet the baby’s head’. That was the last official appearance of Archibald McDougall. Peter took his last bow when he died in 1853.

John and his increasing family moved several times during their residence in Glasgow. I do not know how long John continued as a spirits dealer, but he had not only moved to Queen’s Arcade, Blythswood, in time for the birth of his daughter Mary McDougall McKinlay in 1854, but he was again practising as a slater and had achieved ‘master’ status before this child died in 1858. The third son, John, had been born one year prior in 1857.

The master slater and his family removed to 31 West Russell Street in Blythswood, where the last child, another Mary, was born in 1860 and were still at that address when the 1861 census was taken. John was employing three men and the children were all in school. The family prosperity would seem to have continued into 1871, when the family had moved to 106 Renfrew Street in Blythswood. John’s wife had begun a greengrocery business, the sons were employed tradesmen and there was a servant to assist the daughter Isabella in keeping house.

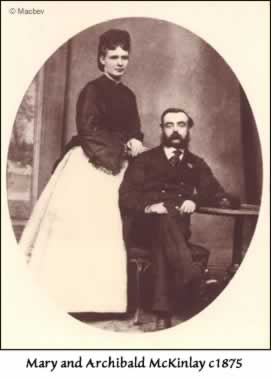

By 1881, there had been major changes. Archibald, the eldest surviving son, now a plumber, had been to Donegal, found himself an Irish Presbyterian wife (Mary Frizzell), married (1874) and acquired three children (John 1875, Isabella, 1877 and Mary, 1879), a sister-in-law and a boarder – all living together in Northburn Street, Glasgow. John, for reasons best known to himself, had retired as a slater and returned to live alone in Campsie – the first in a line of McKinlay men who separated from their wives to live in solitude. His wife Mary was keeping the home fires burning at 106 Renfrew Street, still operating her greengrocery and providing a roof over the heads of her unmarried children – Isabella, John and Mary, as well as three lodgers.

Isabella flew this coop later the same year, marrying William Gillespie and later providing a home for a variety of orphaned nephews and nieces. The second son, Peter, was already away from home, working as a slater in Kilsyth. He married Annie Shaw there in 1882 – a lass with her own interesting family history. The happy couple returned to Glasgow to live at 71 Renfrew Street, not far from Mary, before the birth of their daughter Margaret in 1887.

The youngest daughter, Mary, also married in 1883, giving birth to two children before dying far too young of typhoid fever at the age of 32. John, the third McKinlay son, disappeared without trace between 1881 and 1891. Mary McDougall died in 1890 and although her husband John was still alive, all the arrangements appear to have been handled by Isabella, Peter and Mary’s husband, George Dyer. Archibald was resident in Glasgow, but his name does not appear on the documents. Isabella was also responsible for handling the documentation for her father’s death in Campsie in 1898, but was dead herself two years later.

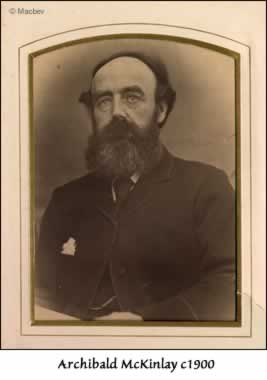

The family was reduced to three: Peter and his questionable offspring, Mary’s son and daughter cared for by their uncle Gillespie then vanishing from view, and Archibald’s thriving brood of one son and four daughters. Archibald was prospering. Now living in Tillie Street, Glasgow, he was a plumber/gasfitter and had apprenticed his son John to the same trade.

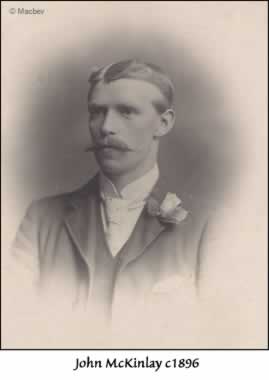

Opportunities and incentives to travel had made exponential growth in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Railway lines criss-crossed the country, the British Empire was flourishing, steam ships were increasingly ousting sail – all providing the Clyde region of Scotland with industrial employment. The newspapers were full of enticing advertisements about life in South Africa, Canada, Australia – in fact anywhere really, rather than chilly Scotland. Young John was the first to respond to the lure of overseas life.

He had served his apprenticeship as a plumber at Nobel’s Dynamite Factory in Ardeer and on qualifying seems to have taken up a position in Johannesburg in South Africa, working for

De Beers in the manufacture of mining explosives. However, the outbreak of the Boer War (1899) saw him repatriated (possibly in 1900) and I was surprised to find him next at the Royal Gunpowder Factory at Waltham Abbey in 1901, where the foreman plumber and the manager were pleased to give him a good reference, prior to his return to South Africa in July 1901.

The family was reduced to three: Peter and his questionable offspring, Mary’s son and daughter cared for by their uncle Gillespie then vanishing from view, and Archibald’s thriving brood of one son and four daughters. Archibald was prospering. Now living in Tillie Street, Glasgow, he was a plumber/gasfitter and had apprenticed his son John to the same trade.

Opportunities and incentives to travel had made exponential growth in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Railway lines criss-crossed the country, the British Empire was flourishing, steam ships were increasingly ousting sail – all providing the Clyde region of Scotland with industrial employment. The newspapers were full of enticing advertisements about life in South Africa, Canada, Australia – in fact anywhere really, rather than chilly Scotland. Young John was the first to respond to the lure of overseas life.

He had served his apprenticeship as a plumber at Nobel’s Dynamite Factory in Ardeer and on qualifying seems to have taken up a position in Johannesburg in South Africa, working for De Beers in the manufacture of mining explosives. However, the outbreak of the Boer War (1899) saw him repatriated (possibly in 1900) and I was surprised to find him next at the Royal Gunpowder Factory at Waltham Abbey in 1901, where the foreman plumber and the manager were pleased to give him a good reference, prior to his return to South Africa in July 1901.

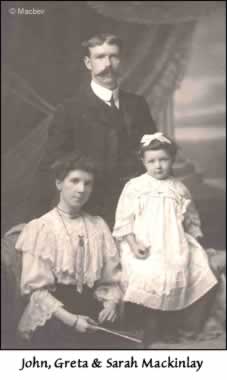

The marriage of John’s sister, Polly (Mary), to Samuel Graham in 1900 led ultimately to the next emigration venture, for the young Grahams, with their two year old son, set sail for Montreal, Canada, in search of a brighter future. John’s courtship of Miss Hooks had prospered and she was to bravely follow him out to Cape Town, to marry him there in 1903.

A rather charming family anecdote states that:- “In Scotland, this cousin (Hugh S. Muirhead) tossed a coin with Dad (John McKinlay) to see who would ask Sarah Hooks (mother) first to marry him. Hugh asked and was turned down (by letters). Sarah was in ‘an awful flutter.’ After Jake and Sarah had walked together for five years, he popped the question. Sarah responded by saying ” Och, Jake, I dinna know ye weel eno'”

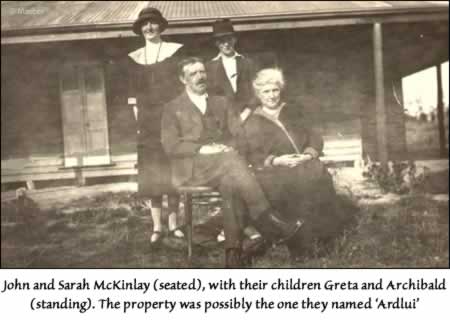

The marriage was followed by the birth of a daughter (Greta) in 1904, and eight years later, a son (Archibald). The families kept in close contact via letters, postcards and all-too-few visits. Back in Stevenston, Archibald was becoming restless. His son was seemingly gone forever to South Africa, his married daughter was in Montreal, her older sister had followed her in 1904, his daughter–in-law’s sister had recently, likewise, followed her heart to Johannesburg. It seemed that emigration was on everyone’s lips. Archibald decided to take the plunge.

The business in Stevenston was sold, and Archie, Mary and the two youngest girls took passage on the ‘Corinthian’, arriving in Montreal in June 1907, and he resumed his trade as plumber. He returned once more to Scotland in 1910 to retrieve his widowed sister-in-law, Hannah, and see her safely on her way to Wilmington, Delaware. 1910 must have been a time of high excitement in the McKinlay household, as John’s wife, Sarah, made the voyage from Cape Town with her small daughter to visit, firstly her own family in Johnston, Renfrewshire, and then her in-laws in Montreal, and a brother who had emigrated to the USA.

The postcards sent about this time reveal the longing to meet with one another,:

Aug 1910: “ P.S. Mother says she will break her heart if you all go to Scotland next summer & not come to Canada. Now remember you can’t go to the one place without going to the other. Georgie”

“Dear Gretta, we are just longing on the time when we will see you in Montreal. I hope you found your Gran and Grand-Pa and all your Aunts well. How did you like your trip across the ocean? Love to Mama and yourself. Geordie.”

“Montreal 21/9 (written to John McKinlay back in South Africa)

My dear J, S[arah] arrived safe & sound. I don’t see any change in her. But Greta, I think she is just dandy. We haven’t made out who she is really like yet. She has got a little cold. But I guess she will be better for her Birthday Party on Sat. Please accept all our best wishes. Bell”

The 1911 census of Canada showed Archibald McKinlay resident in Versailles Street with his wife and daughters Isabella, Georgina and Elizabeth – said daughters miraculously younger after the crossing from Scotland to Canada and earning their living as vendeuses in the French store ‘Magasins’. Polly Graham’s family was increasing in La Chute, Quebec, and in January 1913, Georgie married a fellow Scot, John Lawson, in Montreal prior to moving to Ottumwa, Iowa, USA. Shortly after, her father made a decision to relocate.

7 July 1913: My Dear Children, Just a hurried note to let you know that Mother and I have left Montreal for good and are now staying for a short time in La Chute. Therefore address all future letters after receiving this to Winnipeg. Mother & I are both well and making preparations for our journey west. Sam, Polly & children join in love. Your loving Mother & Father

Back in Cape Town, John McKinlay was finding that his health was suffering (probably the common plumbers’ complaint of lead poisoning) and considering alternatives. With his customary optimism, he was contemplating life as a pioneer farmer in Western Australia, despite having no experience whatsoever. He bought treatises on beekeeping and sheep breeding, and manuals on cropping, and set about persuading his wealthier brother-in-law, William Brown Walker, to supply the capital necessary for establishing a property. World War One was breaking out, but as far as we can tell from the McKinlay correspondence, they were oblivious to it, instead making plans for a new future.

A postcard from Sarah’s father, Walter Hooks, in July 1914 enquires about their activities:-

“……We are sorry you have not got the houses off your hands yet but hope you get it off soon. When is Jack for leaving?…”

It must have struck dismay into the hearts of the family in Canada to discover that Archibald intended to join his son in this new venture, leaving his wife in the care of her daughters. Just when Mary imagined she was settled into a comfortable home with most of her family within easy reach, Archibald was proposing to go to the ends of the earth. One can only imagine the family conferences that must have taken place in Canada, but there is no reflection of this in the business-like note Archibald sent to his son in June 1915:-

“Dear Jack, Yours of the 28th April just to hand. Setting out now to make all arrangements. Will write you later on as soon as can get things definitely fixed. All well. Dad”

John left South Africa for Western Australia, embarking from Cape Town on the ‘SS Miltiades’ on 22nd February 1915 and arriving in Albany, avoiding German submarines on the way. He made his way to Perth where he investigated available properties, finally settling on a farm of some 1551 acres, situated about 16 miles from Tambellup, for which he paid £950. He had left his wife and children behind in the care of his brother and sister-in-law in Johannesburg until such time as he could establish suitable living quarters for them, but his father joined him almost immediately.

There was a forlorn note from Isabella back in Winnipeg, addressed to the farm after Sarah rejoined her husband in 1915:-

“Dear Sarah, Thanks for the book you sent. It was very descriptive of Australia. I think it a very woolly country. You are having it hot now while we are freezing. We expect Georgie soon. I trust it will be warmer – Iowa is much hotter than here. Mother is well but seems lost without Father. I often think it was a mistake letting him go. Trusting you are all in the best of health. Will write soon.

Love to all, from Bell”

Sadly, Mary never saw her husband again as he died at Tambellup in 1922.

John did not prosper as a farmer. Despite his best endeavours, he was obliged to move on from one property to another, being overwhelmed by drought, rabbits and the ‘Great Depression’. He spent his latter years living with his son, Archibald, helping run the farm for his daughter-in-law, while his son was man-powered into a shearing team during WW2. Sarah lived with her daughter Greta, assisting with the bairns and getting under her daughter’s feet in the kitchen.

John exhibited a resurgence of independence after the war ended, leading a fairly restless life between 1947 and 1949, occasionally staying with his son, at other times trying his hand at ventures such as prospecting for gold in Kalgoorlie. In 1949, he was moved to try to build a home once more, on land in the low-lying central part of Mandurah. He camped out in a tent while he wrestled with plans and a fruitless effort to acquire the necessary timbers, and in between times, fishing from the local jetty. A damp winter resulted in illness severe enough to cause his son and son-in-law to forcibly remove him from his tent and take him to hospital, where he slowly improved enough in health to join Archibald on his new property. John helped to re-roof this farmhouse and was still there when his little granddaughter Edith died of diphtheria in August of that year. This family tragedy may have been the last straw for John. He died a month later, on 2nd September 1950 in Narrogin.

John’s son, Archibald, displayed few signs of itchy feet until later in life, when he sold the farm on the death of his wife, travelled to America to visit his cousins and aunts, found a new wife in a shipboard romance and returned to Australia to live life on the road in a caravan – joining the hordes of grey nomads who endlessly toured this continent. Archie’s son, John, has inherited the family trait and is constantly tempted to explore distant horizons.

Macbev

© Macbev 2009

SOURCES

Memories of Flat Rocks,1915-1926 from Margaret (Greta) Lymon née Mackinlay.

ScotlandsPeople for OPRI & SRI Births & Christenings; Marriages & Deaths

Ancestry for censuses for Scotland, 1841-1901

FamilySearch for International Genealogical Index

Library and Archives of Canada for Passenger Lists, 1865-1922

Census of Canada 1911, Quebec/Montreal/ St Antoine Sub Dist.# 11 pg 14; sched. 126.

Ancestry: Quebec Vital and Church Records (Drouin Collection), 1621-1967

Ancestry: Iowa State Census Collection, 1836-1925

Australian Cemeteries: Tambellup Cemetery

Oz Burials Headstone Transcriptions: Narrogin

Ancestry: Australian Electoral Rolls, 1901-1954

The Western Australian Post Office Directories

Ayreshire Roots for Ardrossan and Saltcoats Herald

BDM, Marriages: Donegal Letterkenny/1874 June Q vol 7 page 149.

Weslyan Methodist Church (Somerset West, Cape Colony, South Africa) Archibald Mackinley 1912 baptism.

BDM, 1912/Birth Stellenbosch/Colony of the Cape of Good Hope; book no. 2; cert.no.7.