Our traditional image of a pretty village centre, inhabited by the butcher, baker, candlestick maker and perhaps a milliner for a Jane Austen character to buy a new bonnet from, evolved slowly from the middle ages and only really came into being in the 19th century.

MARKETS AND FAIRS

In the middle ages every small town had its market day when the farmers and craftsmen from the surrounding area would all come together and sell their produce and wares. At this time the population lived close to the land and there was very little that the average peasant couldn’t grow or make for himself. The markets served as a place for everyone to find the few articles they needed and for them to sell any surplus produce, enabling them to pay their taxes.

Life and expectations amongst the ordinary population were very simple, they thought in terms of food, heating and basic clothing, they did not have extra income for luxuries and, outside of London and the nobility, there were no luxuries on offer. Typical market goods were foodstuffs, bread, meat, ale and cooked meats, and household articles such as leather goods, wood and metal, firewood, candles, cloth and linen.

The markets were strictly regulated with sellers having to pay for their stands just as they do today and with the best spots and tariffs being given to local people. There was no place for middlemen, in fact many towns actively regulated against them and prosecuted culprits. Trade was restricted to certain times to allow all customers fair access to the best produce and to enable the town authorities to keep an eye on the transactions. Starter’s orders might be a market bell as in Yarmouth, the church bells ringing for mass or someone declaring that it was “broad day”.

The town authorities controlled buying and selling in these markets and if the town was large enough to have guilds for the different trades, their protectionist rules were added to the list. These rules were seldom the same from one town to another but all had the same objective to keep the trade in the market for the guilds’ members and to create a healthy income for the town authorities in tolls and duties. This period also saw the beginning of fixed measures and weights for different goods such as corn and ale to be sold in as the town authorities tried to increase their markets’ reputations by showing that they were a safe place to do business. However, short measures and different ruses to hand over less produce than was actually being paid for soon sprung up, meaning that the average medieval buyer had to have a very sharp eye.

Let us have a closer look at how the baker, butcher and brewer earned a living during this period. Both bread and ale were staples of the medieval diet and both depended on the corn crop. Regular meetings of the town authorities at the assizes controlled prices.

They could not alter the price of the bread, which was sold in farthing, halfpenny and penny loaves, so they decided on the size of the bread to be had for each amount depending on the availability of corn. The same happened with ale, the assize regulated the strength of the ale sold in the standard penny gallon.

Bakers not only baked their bread, but in a society where only the wealthy had an oven, they baked bread prepared by the villagers and homemade popular dishes such as “meat chopped small” and “pease pudding”. They also had a sideline in making horse bread, which was fed to horses instead of hay, hay being generally reserved for cattle. It was made from peas and beans, which were not eaten by the population in the middle ages, vegetables being virtually absent from their diet. Before the harvest when the size of loaves was decreasing as the corn supplies ran out, poor people often turned to horse bread to ward off hunger.

Ale was the drink of the ordinary people. Nobody drank water in the Middle Ages if they could help it, not only was it dangerous but it also carried with it the stigma of poverty. Ale was drunk with every meal and most well organised households would buy malt and brew their own supply. Surprisingly for a time when most trades were very strictly regulated, anyone could become a brewer. The authorities only asked that a sign made up of a bush of leaves on a pole be hung outside the premises, so that the new brew could be tested and the size of the tankards checked before it was sold to the public.

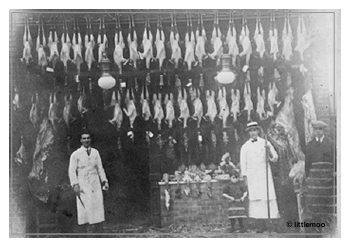

Meat was not expensive and many people, even those living in towns, would have had their own animals. Butchers still did a good trade though, buying live animals, slaughtering them, selling their hides and the tallow, before cutting up the meat to sell in the market. The meat was meant to look and smell good. It was against the law to sell meat that had come from an animal that had died naturally and it should never be sold by candlelight.

Although trading was done almost exclusively in the weekly markets, by the 14th century most towns would have had a general merchant. He would probably have worked out of his cellar or a room in his own house selling goods that could not be found locally. He would have sold anything from furniture and hardware to second-hand clothes, wool and garden seeds depending on what he found at the fairs held once a year in different parts of the country.

Fairs brought together craftsmen, merchants, traders and farmers from all over the country. The biggest ones even had international participants, bringing Flemish linens, armour from Milan and wine from France. Customers, including the royal household, would come to buy supplies for the summer or winter depending on when the fair was held, and craftsmen came to buy the raw materials for their trades. They must have been colourful, noisy affairs and possibly very muddy under foot when the weather was bad and hundreds of people had churned up the ground. They would have been a good place to catch up on the news and events in the rest of the country and abroad and they were also very profitable for the lucky holders of the royal permission, which enabled them to hold the fair and to charge the different stallholders for their pitch.

GENERAL GOODS MERCHANTS

The first signs in a change away from the traditional medieval system of markets came with the population explosion and rising prosperity in London during the 16th century. London began to rely on food from outside to feed its growing population, its richer inhabitants started to demand luxury goods and poorer people were drawn to the capital to supply the labour involved in producing them.

Appearance and dress became important; clothes were a serious investment to be looked after and sold on when they had served their time. Anything exotic and foreign was exciting and merchants were soon quick to pick up on this. Dorothy Davis in her “A History of Shopping” writes that the highest praise for a piece of clothing was “far-fetched, meaning – literally – just that” closely followed by “Pray, what did you pay for it?”

Goods became more plentiful. The general goods merchant was now able to start specialising and stocking a shop. Craftsmen had always sold their own production but now with the influx of poorer craftsmen from the countryside and foreign refugees, the craftsmen who already had shops in London started to stock their fellow craftsmen’s goods as well. Gradually they moved away from manufacturing and became retailers only.

At the same time new highly specialised trades developed, first in gun making and then in musical instruments, watches and spectacles in the 17th century. These new craftsmen created individual pieces to order and so dealt directly with the customer. Food selling however was still largely confined to markets where the city authorities could keep control and make a tidy profit.

In the old towns the drapers, mercers and grocers were apprenticed, like Merry’s 3x great grandfather David Maynard, and then elected freemen. They tried very hard to keep their monopoly on retail.

It wasn’t until 1835 and the Municipals Corporation Act that it became possible to open a shop anywhere in England, but in the newer manufacturing towns, which lacked the strict regulations of the older corporate ones, people were free to follow the trade they wished and this included shop keeping.

So, by the end of the 18th century shops had become usual in towns and most large villages. They still weren’t quite the shops of today, though. There were no fixed prices, everything was to be haggled over and as there were no regulations for manufacturing, the shopper had to judge the quality of what they were buying for themselves. They also had to contend with the problem of forged money and a lack of smaller coins. As a result of this, credit was given quite freely. Suppliers gave credit to the shopkeepers, often of up to nine months, and shopkeepers gave their established customers long credit in turn.

Food scares are nothing new and the 18th century shopper was very much aware that strange and often dangerous ingredients might have found their way into the food. Dust was added to tea, sand to sugar, lime was mixed with flour, pickles were coloured with poisonous verdigris to make them nice and green and all sorts of truly hair-raising additions were added to the householder’s daily bread.

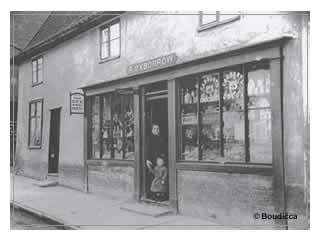

The shops themselves were mostly small and cramped with transactions taking place across open windows but in London some of the smarter shops were beginning to make use of plate glass in their windows allowing for the beginnings of window displays.

In the 19th century fresh food and vegetables were still mostly bought in markets and meat and fish sales were divided between shops and markets. Even in London there was still a direct link between the food grown in the countryside outside London and the stalls in the market manned by the farmer and his wife.

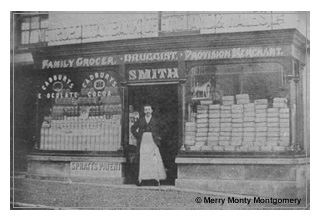

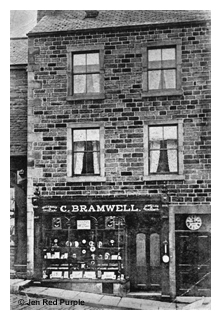

At this time nearly all shops were small independent ones run by their owner who was a skilled man in his trade of shop keeping. He would have served an apprenticeship and learned the intricacies of where to buy, how to strike a good bargain, how to judge the quality of stock and how to sell at the right price to get a bargain.

Butchers needed to be able to choose their animals carefully, to slaughter and to prepare the joints themselves in their sheds behind their shops, grocers needed to know how to blend, grind, weigh and package their stock and even haberdashers had to know how to cut the threads that they bought by the pound into lengths for their customers.

From Pigot’s Directory for Sussex 1832-34 we can get an idea of the various shops in a small market town such as Crawley and the bigger one of Battle. Crawley counted just 394 inhabitants in 1831 and held a “very small” market every Thursday. There were two butchers, two bakers, four beer retailers, four grocers, three drapers, three boot and shoe makers, one watch and clock maker, one hairdresser, two tailors, a dressmaker and one breeches maker and glover.

Battle had nearly 3000 inhabitants in 1831 and also held its market on Thursday. It boasted six butchers, seven bakers, six grocers, seven boot and shoe makers, four tailors, two druggists, two watch and clock makers, two saddlers, three linen drapers, two hardwaremen and ironmongers, six taverns and public houses, a wine and spirit merchant, a hairdresser and perfumer, a gun smith, a glover, a milliner and dress maker, a printer and binder, a straw hat maker, a clog and pattern maker and a jeweller and toy dealer.

The social standing of a 19th century shopkeeper was not very high. In Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford, Miss Jessie Brown scandalises the good ladies by cheerfully admitting that her uncle is a shopkeeper in Edinburgh.

“Miss Jenkyns tried to drown this confession by a terrible cough – for the Honourable Mrs Jamieson was sitting at the card-table nearest Miss Jessie, and what would she say or think, if she found out she was in the same room with a shopkeeper’s niece!”

BAZAAR TO DEPARTMENT STORE

There were, of course, exceptions to this rule and they were successful drapers and grocers. In the small world of shops the drapers and haberdashers had always stood out from the others. At the end of the 18th century it was not unusual for drapers in towns around the country to send a representative to London to seek out and buy the latest fabrics and trimmings for their customers. The drapers in the city of London acted as wholesalers and retailers. Gradually they took on bigger premises and increased their range of goods. Some familiar names from today started up in business at this time. In 1790 Dickens and Smith opened a drapery shop in Oxford Street. They moved to Regent Street in 1835 and later became Dickens and Jones.

Britain’s love of fashion went from strength to strength from the “far-fetched” days of the late 16th to the “naked fashion” days of Jane Austen. Mrs Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, in the midst of her anxiety about her youngest daughter Lydia’s elopement with the scoundrel Wickham, cannot forget the all important subject of Lydia’s clothes.

“…find them out, wherever they may be; and if they are not married already, make them marry…And tell my dear Lydia, not to give any directions about her clothes till she has seen me, for she does not know which are the best warehouses.”

These warehouses were in fact large shops and although Mrs Bennet talks of clothes, ready made dresses were not available until the end of the 19th century and the warehouses only sold material, trimmings, bonnets and shawls.

Many a successful warehouse drapery business may have started life with a market stall or by renting a counter in a bazaar. Bazaars were owned by a single proprietor. They were large buildings often arranged over two floors and the owner rented out counters to individual retailers.

The first was the Soho Bazaar in London. It very quickly became a success and many similar bazaars soon sprung up in towns all over the country. Tammy C. Whitlock in her book “Crime, Gender and consumer Culture in 19th century England” cites “A visit to the Bazaar” which describes the various retailers to be found there, these included a toy maker, a gun smith, an artificial flower maker, a milliner, a hosier, an exotic plant seller and a hair merchant.

The other unusual characteristic of the bazaar was that it was considered a safe place for women to work. By the 1840s when Charles Knight wrote his “Knight’s London” he describes that “a plain and modest style of dress” is insisted on for the women who work there and that there is “a matron at hand to superintend the whole”.

It is tempting to see in these bazaars the beginning of our modern department stores but the credit for the first ever department store is usually given to the “Bon Marché” in Paris. Alison Adburgham in her “Shops and Shopping” does not agree with this. She feels that two British provincial shops, Bainbridge’s of Newcastle and Kendal Milne & Faulkner of Manchester, had branched out into selling goods from different departments before Monsieur and Madame Bouçicauts had opened their shop in 1852. They had also banished haggling by bringing in fixed prices and their customers were encouraged to wander freely around the shop looking at the goods on offer at their leisure.

The second half of the 19th century saw a big change in food retailing as the population increased, people moved away from the countryside into the towns, communications improved with the railway and manufacturing took off.

Living standards were rising and the working classes, who were receiving regular wages, were creating a stable demand for basic household necessities.

These basic goods, tea, flour, sugar, bacon, butter, cheese and eggs could now be imported cheaply from abroad. As yet there was nowhere where people could buy all these goods in one place. Grocers dealt in dry goods and would not stock perishable ones such as eggs and butter. They also considered themselves as retailers to the well to do and not to the working classes. It took a new breed of retailer to realise the potential of providing the working classes with the goods they needed.

One such retailer was Thomas Lipton of later tea fame. In 1872 he opened his first grocery shop in Glasgow in the working class area of Anderston. Twenty-six years later he had 245 branches of his “Lipton’s Markets” all over the country. His idea and the idea of the other early grocery chains, was to import cheap goods from abroad and to sell them in their branches. The shops were kept simple and to a set design. The goods were identical and few in number, just the basic foodstuffs mentioned above and they were sold for cash not credit. The staff was employed to sell only, the stocking and the pricing was dealt with at headquarters. The shops often had a “barker” out on the pavement, calling out the prices, describing the goods and generally trying by every means possible to entice customers inside.

Thomas Lipton visited India and its tea plantations in 1890. He soon realised that if he wanted to reduce the price of tea to make it more readily available to the working classes in his “markets” he would have to cut out the middle men, who were making very tidy profits. He bought four plantations in what was Ceylon and started to grow and import his own tea. Other big grocery companies did the same thing, buying their own dairies and generally moving into production in order to keep their prices down. The formula worked and the old fashioned grocers were soon forced to expand their stock to include perishable and imported goods to stay in business.

Out of these pioneering drapery warehouses and multiple branch grocery shops have grown our department stores and supermarkets. Early department stores clearly caused some frustrations and problems for ordinary mortals as is demonstrated by the following quotation:

“THE PLEASURES OF SHOPPING.

DEAR PUNCH,

I AM one of the old school, and like the old ways. Judge then, my old friend, of the shock to my equanimity the other day. I required six pennyworth of coat buttons, and went into the first shop which looked like one for the sale of that article. On entering, I walked up to the counter and said to the man, “I want some buttons.”

“Oh, Sir! said he, “please go to the other side, to the ‘Button Department,’ this is Baby Linen.”

I went to the other side, and “I want some buttons,” said I.

“What do you want them for?”

“For my coat.”

“Oh then, Sir, if you please, to the next shop, this is the ‘Ladies’ Button Department.'”

I was accordingly ushered by a perfumed ladies’ button department gentleman, through several gilded corridors, then up one pair of stairs, and down another, and finally found myself roaming at large in the gentlemen’s department general. I went up to the first counter, and repeated my request.

“Oh, Sir, if you please,” said the attendant, ” the other side; this is the ‘Gentlemen’s Flannel Department.'”

It is needless to describe the thing any further. Suffice it to say that, after applying at the Gentlemen’s hosiery Department, running a tilt at the Gentlemen’s Pantaloon Department, and being nearly stranded on the Gentlemen’s Fancy Shirt Department, I got what I wanted, sixpennyworth of buttons.

Ever yours, dear Punch,

JOHN STRONG.

Punch, May 2, 1868″

Nothing changes!

Georgette

© Georgette 2008