On 22nd May 1851 the New South Wales government officially announced that payable gold had been discovered in an area near Bathurst to the west of Sydney. This would be the catalyst for a dramatic and long-lasting effect on the economic, social, political and cultural development of the struggling colonies which combined with an immense wave of immigration, signaled the beginning of Australia’s golden days.

Reports of small gold finds in NSW were made as early as 1814 when the building of the road over the Blue Mountains from Sydney was commenced. Government surveyor, James McBrien, found gold traces in the Bathurst Plains area, west of Sydney, in 1823. In the same year a convict working in the area also found traces but received a lashing for his troubles. Polish geologist and explorer Count Strzelecki, visiting the colony in 1839-40, identified various areas as potential sites for gold. During the 1840s more rumours of gold finds surfaced. British geologist, Sir Roderick Murchison, noted that the area near Bathurst was a likely source. Small finds by farmers, surveyors and shepherds were sold or disposed of quietly to jewellers lest word get out. When shown gold specimens by the Rev William Clarke in 1841 Governor Gipps said, “Put it away, Mr Clarke or we shall all have our throats cut!”

Although transportation to NSW officially ceased in 1840, it was still basically a penal colony with a sizable percentage of convicts serving their time and providing cheap labour. The rest of the population was comprised of free settlers, soldiers, ex-convicts and their families. Few free settlers were attracted to the colony and many of the migrants arriving from Britain were on Bounty or government assisted passages. They came from rural areas such as Kent and Sussex and were tradesman and agricultural workers who came to fill similar positions in rural NSW. Few could afford to purchase their own land and many faced great poverty.

Financially the colony was in depression, close to bankruptcy and payable gold finds would have secured its economic future. In spite of this authorities clung to the notion of gold as a ‘dangerous’ commodity ensuring that reports of finds were squashed for a number of reasons.

It was believed that chaos and civil strife would ensue if gold panic erupted. Convicts and other workers would rebel and rush off in search of gold. A disruption to business and society was also feared should servants, tradesmen and others join in the pursuit of the yellow metal. Landholders – farmers and squatters, many of them emancipated convicts, worried that their lands and livestock would be endangered if undesirables from the towns began to destroy their pastures with indiscriminate digging. They too would lose their cheap supply of workers. In South Australia and Port Phillip, soon to become known as Victoria, small finds were also suppressed by the authorities for the same reasons.

It was an event on the other side of the world that forced a change in the attitude of the NSW and Victorian governments. On 24th January 1848 gold was discovered by James Marshall at John Sutter’s sawmill on the America River at Coloma in California. Sutter was reluctant to publicise the find, fearing the loss of his agricultural and mill workers and the problems that would arise from gold–seeking hordes descending on his lands. The discovery remained a secret until December 1848, and when made public – the rush was on!

Word of the Californian gold finds reached the Australian colonies by 1849 and large numbers of hopeful prospectors joined the rush to California. The impact of the loss of workers, skilled and unskilled, brought huge problems for the authorities in NSW, to the point where by 1851 it was decided to offer a reward for the discovery of payable gold. It was time to see whether earlier reports of gold finds had any substance!

One such prospector was Edward Hargraves. An Englishman, seaman, publican and adventurer who had settled in NSW, he travelled to California in 1849. Although unsuccessful in making his fortune on the diggings, Hargraves was a keen observer of the gold bearing terrain. He mastered the processes of panning, cradles and sluicing for gold and returned to NSW convinced that an area he had seen near Bathurst bore great similarities to the Californian diggings.

Returning to this area in February 1851, Hargraves sought out a John Lister who was known to have found gold traces there. Lister led him to Summer Hill Creek where Hargraves panned sufficient small specks to be convinced that there was much more to be found. He then organised two brothers, James and William Tom, to accompany him to the Summer Hill Creek site. He instructed the brothers in the skills he had acquired in the Californian fields and arranged for them to prospect there. On the basis of further finds worth about £13, Hargraves rushed back to Sydney to claim the reward for the finding of payable gold from the Colonial Secretary. He neglected to mention the role of Lister and the Toms brothers in the gold discoveries.

Word of the finds in the area, now named Ophir after the fabled rich biblical region, spread rapidly. By May 1851 a government geologist confirmed that the find was indeed payable and a public announcement duly made. Within a month there were said to be over 400 prospectors working the Ophir diggings.

Hargraves was rewarded with £500, but never acknowledged Lister and the Toms. A further reward saw him appointed as Crown Commissioner of the Goldfields with an additional payment of £10,000. It was, Hargraves claimed, “never my intention…to work for gold but to make the discovery and rely on the government and the country for my reward”. When the Tom brothers tried to claim part reward they were defeated in a court case won by Hargraves and their role in the discovery of payable gold was not acknowledged until many years later.

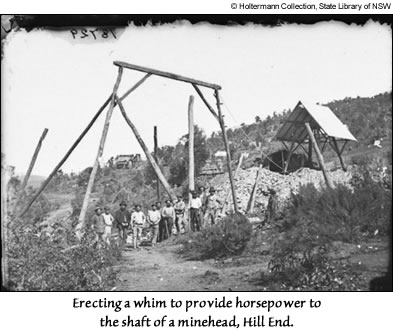

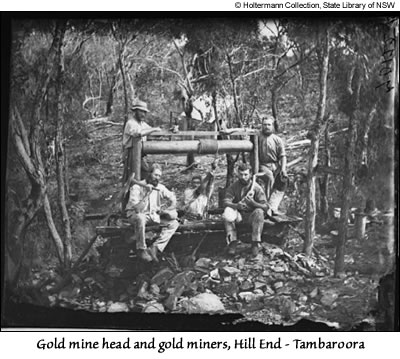

Many prospectors were disappointed to find that Ophir did not yield great riches and left the area disillusioned. Others stayed and began to find payable gold in nearby locations such as Sofala and Tambaroora near the Turon River. New gold bearing areas were located to the west and south and as further discoveries became known the trickle of people appearing on diggings increased dramatically until it became a flood. Clerks, servants, tradesmen, lawyers, sailors, soldiers, teachers deserted their work and headed over the mountains to seek their Eldorado. Gold fever had struck!

The Victorian authorities, concerned at the sudden loss of people from all walks of life to the NSW diggings, put up a reward of £200 for anyone finding payable gold within 200 miles of Melbourne. In July 1851 gold was found at Clunes, a month later at Bunninyong near Ballarat.

The genie was out of the bottle, the gold rushes were under way and by the end of 1851 NSW and Victoria were experiencing the start of a previously unimaginable period of economic, social and political development. Gold was the stimulus that enabled financially depressed penal colonies to move towards a future as a strong and vibrant nation.

The lure of gold caused a huge wave migration of people into Australia from all over the world. Between 1851 and 1871 the total population of Australia increased from 430,000 to 1.7 million. This massive surge was essential in providing the manpower for the fledgling nation to survive.

Migrants brought with them a range of skills and knowledge that contributed to all aspects of life – financial, social, cultural, religious, technological and political. Miners from Cornwall and California brought mining know-how and skill in hard rock mining that was to be invaluable for claiming the metal. Migration brought settlers from countries other than Britain – from China, America, Germany, Poland and other European countries. The diversity of languages, skills, customs and beliefs created the foundation for a cosmopolitan and multicultural society. Immigration also boosted the rates of marriages and births rose dramatically.

Not all who flocked to the gold-fields took up their picks and gold pans. Many saw the demand for provisions and supplies essential to the diggers and so established businesses to meet these needs. Butchers, bankers, blacksmiths, tailors, carpenters etc were in strong demand. Rural areas were no longer populated solely by farmers, graziers and their workers. Migrants contributed at all levels and in many fields from professional to trades. Towns sprang up to service the diggers and became the hubs of strong rural communities with churches, schools, and community resources.

In every township close to the diggings hotels and pubs appeared in great numbers. Mining was thirsty work and some townships boasted 30 or more, each doing a roaring trade. Banks appeared in significant numbers. There was great scope for entrepreneurs and innovators and demand for all services was high. Often business people in the townships subsidised syndicates of miners and their ventures in return for a share of their gold profits.

In the early years living conditions for miners and their families on the gold-fields were hazardous and impoverished. Supplies of clean drinking water were often scarce, sanitation poor and diseases rife. Mining was a dangerous occupation and casualties from accidents high. As townships became more permanent, small hospitals and health care professionals arrived to fill a huge demand for care.

Gold brought rapid economic growth and expansion to NSW and the newly named Victoria. Investment in mines and mining townships came from local and foreign sources. The burgeoning population led to the expansion of primary production to feed and meet the demands of rapidly growing towns. Graziers increased livestock numbers to profit from the local demand for meat, hides and horses while farmers planted more grains to satisfy the strong domestic market. Where possible goods and implements were manufactured and supplied locally further increasing the economic viability of the new towns. Skills brought by migrants supplemented and facilitated the local production of necessities from implements to boots and clothing.

With the need to move people, provisions and gold to and from the mining townships, transport infrastructure took on greater importance. The earliest roads to the diggings were rough dirt tracks that challenged any form of wheeled transport. Packhorses and mules or bullock drays conveyed the heavy loads, while people struggled on foot pushing wheel barrows containing their possessions. Railways did not reach mining towns until late 1860/70s. An American, Freeman Cobb, with his associates, introduced a specially designed coach to convey passengers and light freight over rough roads from town to country, and Cobb & Co was born.

The need to provide safety to those using the roads and the transport of gold led to an increase in numbers of troopers (police). Thieves and bushrangers roamed at will through rural areas causing terror and consternation. Bolters, escaped convicts, were opportunistic and often brutal thieves who attacked indiscriminately. Police numbers were initially low and justice on the gold-fields was often rudimentary.

Gold was responsible for triggering significant social changes within the colonies. In harsh physical environments, where temperature extremes, mud and hard physical slog were the norm, on the diggings all men became equal no matter their previous status or class. Former convict toiled beside former banker, former servant beside former lawyer, Irishman beside Frenchman – all intent on securing their individual dream of ‘striking it rich!’ On the gold-fields the British concept of ‘class’ was extinguished. It was a matter of ‘who’ not ‘what’ you were, and so a concept of social equality was established. Miners also found it more effective to work as small groups rather than strike out on their own.

The perilous and difficult conditions on the diggings also led to the concept of mateship, of reliance for support from one’s mate at times of trouble. Mateship was absorbed into the Australian psyche and became a facet of the Australian national identity on the battlefields of war from WWI to the present.

In order to preserve law and order on the diggings the NSW and Victorian governments appointed Gold Commissioners – magistrates in charge of a body of police (troopers). A system of licensing was introduced whereby a tax of 30 shillings per month per mining lease was levied regardless of whether a lease produced gold or not. Inspectors could demand to see licences, also known as miner’s rights and viewed as forms of unfair taxation, at any time.

Mining licences, inspectors and injustices associated with them were a root cause of the first and only armed civil rebellion in Australia. Protesting miners in NSW succeeded in having fees reduced to 10 shillings, but in November 1854, miners at Ballarat, Victoria, rebelled against attempts to double the price of licences and the lack of voting rights for adult male holders. In a stockade they constructed at Eureka they flew the Southern Cross flag as a sign of protest. In the early hours of 3rd December some 400 police and soldiers launched an attack on about 150 miners inside the stockade. In minutes 22 miners and 5 police troopers were killed with others dying later from their wounds. As a result of the commission that followed, miners won the rights they had sought and the licence system was replaced by mining wardens. The Eureka Rebellion brought about the reform of unfair laws and is considered by many as the birthplace of Australian democracy.

Income from gold enabled major changes in education with universities and other institutions for advanced learning established. Theatres, art galleries, libraries and public gardens were developed. Newspapers and journals flourished as did politics, religious, cultural and sporting interests. Exploratory expeditions opened up new areas and possibilities for settlement, mining and pastoral activities.

The discovery of gold and all its consequences – migration, rapid social, political and economic growth and development – caused a significant change in the attitude of the British government towards control of the colonies. The transportation of convicts to Victoria and Tasmania ceased in 1853 and only Western Australia accepted convicts until 1868. Thanks to gold the colonies were no longer dumping grounds for unwanted British felons and the journey to a democratic nationhood had begun.

Gold was discovered in many other locations – Queensland in 1858, Western Australia in 1863, Northern Territory in 1865, Tasmania in 1886, but the richest discoveries came in the 1890s in Kalgoorlie and Coolgardie, WA. Gold continues to be a major income earner and Australia is in the top four gold producing nations in the world.

Sunny Kate

© Sunny Kate 2009

SOURCES

The Rush That Never Ended by Geoffrey Blainey. University of Melbourne Press 1963.

To the Diggings! A celebration of the 150th anniversary of the discovery of gold in Australia by Geoffrey Hocking. Lothian Books 2000.

The Cradle of a Nation by John Rule. 1979

Chronicle of Australia published by Chronicle Australasia Pty Ltd 1993.

The Fatal Shore by Robert Hughes William Collins and Son, 1986. Chapter 16

Images from the Holtermann Collection, State Library of NSW are used with the kind permission of the State Library of New South Wales. All enquiries about the images including all requests for copies should be made to the Mitchell Library.