As a child I often heard stories about how my grandmother’s family had been pioneers in one of the first gold-rush towns in New South Wales (NSW). Four years ago, when I decided to search for my ancestral roots, this family was my starting point. My journey of discovery led me to Tambaroora, Hill End, and my great great grandparents, James and Sarah Barlow.

Following the ancestral trail from my grandmother to her parents was easily accomplished through my family knowledge and NSW birth, marriage and death records. My grandmother’s mother, Adelaide, was born in 1856 at Tambaroora, NSW. Although absent from any current map, a quick check on-line showed me that Tambaroora was one of the early townships that sprang up when gold was discovered in NSW in 1851.

It was the lure of the golden hills of the Bathurst area that proved too strong for her parents, James and Sarah Barlow, who like thousands of others, succumbed to a dream of finding great riches. In the early 1850s the Barlows deserted their home in Sydney to cross the Blue Mountains and confront the challenges of the unknown.

Early efforts to discover much about James and Sarah proved as frustrating as panning for gold. A copy of their 1848 NSW marriage certificate contains little information. It shows their names, parishes, officiating minister and witnesses, but no clues as to whether they were born in NSW, were migrants or former convicts. Sarah’s death certificate gives her age, place of birth, name of parents and length of time in NSW, while that of James contains no parent names, a birthplace of Manchester in about 1811 and an estimated 60 years residence in NSW.

The NSW BMD indexes provided further clues as to the location of the couple after their marriage and indicated that 3 of their 7 children were born in Sydney by 1852. Births for the younger children were registered in the gold-fields – one in 1854 at Sofala with the three youngest at Tambaroora between 1856 and 1862. This placed the Barlows amongst the early families to move into the area.

James and Sarah Barlow remained elusive in spite of many months of searching. Our visit to Hill End, now a tiny township managed as an historic site by NSW National Parks, did not yield any new information about them, nor could I find their graves in the local cemetery. Fortunately, a short time later, I struck gold with two new contacts who had vital pieces to add to the picture.

3x great grandfather, Henry Munn Knowlden (or Knowlding/Knoring), was a blacksmith, probably born about 1792 in the Romney Marsh/Brooklands area of Kent where his father John (or Henry) was supposedly a grazer. Parish records showed that Henry Knowlden married Lucy Cross at Peasmarsh, Sussex, on 29th November 1823.

Sarah Knowlding (or Knowlden), their eldest daughter and my great great grandmother, was born at Beckley, Sussex, on 2nd January 1825 and baptised there on 6th February 1825. Her siblings were George (born 1826), Charlotte (born 1828), Henry (born 1830), Adelaide (born 1832) and Edward (born 1833).

The NSW Assisted Immigration Passenger List shows a widowed Henry Knoring, aged 45, with five children, departed from Dymchurch, Kent, aboard the ‘Prince Regent’ as bounty immigrants to NSW. The ship left London on 11th November 1838 and arrived at Botany Bay on 17th March 1839. The same record shows that Mrs Knoring was, “dead some time since”. Whether Lucy died at sea or before the family left Kent is unclear and I have not found an entry for her in the English death index. Edward is believed to have died in infancy. Henry must have believed that emigration to a distant penal colony offered his family a better life than they would have had in Sussex or Kent.

Contemporary accounts of conditions for immigrants aboard ships of this period paint a grim picture of the circumstances and privations that prevailed.

Assisted migrants travelled steerage – cramped accommodation in communal areas with little storage space for possessions. Passengers had to supply their own bedding, as well as their own clothing, personal possessions and possibly some tools. On some ships families were allocated space together, on others males and females were segregated. Food supplied on the ship included salt beef/pork, flour, tea, salt, sugar and oatmeal. Fresh food was available only when a ship called in at Cape Town on route.

}During the 4½ month voyage to NSW, 14 year old Sarah would have been responsible for the care of her younger siblings – supervising them, maintaining their clothing, caring for them if they were ill. Shipboard life was difficult for young children with opportunities for play and movement about the ship limited, especially in rough weather. During times of high seas and storms passengers were confined below decks, sometimes for several days without access to fresh air and exercise.

A surgeon, present on each ship, was responsible for ensuring the availability of anti-scurvy foods for passengers and crew, as well as supervising an appropriate standard of hygiene amongst the immigrants. Sea sickness and other illnesses were common and strict adherence to basic hygiene matters was critical in order to prevent the spread of contagious diseases. Unfortunately during 1838 and 1839 there were fatalities from outbreaks of typhoid on several ships that carried migrants to Sydney.

On arrival in Sydney as a bounty immigrant, Henry’s blacksmith skills would have provided him with work but nothing is known of where the family lived. Most likely Sarah continued to look after her siblings until they had completed some schooling and found work. Conditions for migrants were often poor as the colony of NSW was suffering financial depression.

On 6th January 1848 Sarah married James Barlow at St James Church of England, Sydney. She was just turned 23 and James was about 36.

Through a chance contact with a distant cousin (also descended from and researching the Barlows), I was delighted to be given an anecdotal account by his grandfather Thomas Roberts. Thomas was born at Tambaroora in 1873 and often visited his grandparents James and Sarah at their home in their later years.

He described James as:

“..a man of character who migrated from Manchester about 1833. Worked for officers of the military and used to cook meals for them. Probably his payment from the officers would be rum (though the NSW Corps had been passed on) the coinage of the era.He was wont to fight in bare knuckle fights for the pleasure of the aforesaid officers. Being a very strongly built young man, he usually won these contests, and was paid no doubt in the coinage of the time.”

Little is known about James Barlow’s roots, however family researchers, including myself, are convinced by various old ‘family talk’ that he arrived in NSW not as a migrant, but as a convict. One possible candidate, sentenced in Lancaster in 1830 to 14 years transportation, arrived in Sydney aboard the ‘Royal Admiral’ in 1831 and received a certificate of freedom in 1845. The other, sentenced at Northampton Assizes in 1833, arrived aboard the ‘Fairlie’ in the same year. The description of James above supports his probable convict status. Convicts were assigned to work for the military and 15 years between his arrival and his marriage suggests he was ‘busy’ elsewhere. While previous generations of Barlow descendants might not have been keen to claim a convict, my generation is very happy to do so.

According to Thomas, before her marriage Sarah worked for the wife of well known Sydney businessman, Anthony Hordern, assisting Mrs Hordern with their young children. She was literate and no doubt well suited to the job.

He described a wedding present from the Horderns to the newly wed Barlows.

“In their home at Tambaroora later was an eight day clock, a wedding present from Mrs Hordern. The clock always intrigued me as it bore a picture of Trafalgar Square, London.

I was also told that Mr Hordern offered to set the Barlow family up in business. But they caught the gold fever badly and went over the mountains to make their fortunes in the new Eldorado.

On the breaking out of the Gold Rush in 1851, Grandfather hastened to the alluvial diggings at Wallaby Rocks on the Turon river near Sofala and later proceeded to the Tambaroora diggings where he lived the remainder of his life.”

Sarah’s father, Henry Knowlden, accompanied the Barlows to the gold-fields where his blacksmithing skills would have been in great demand. He died at Tambaroora in 1866 after a tree fell on him.

Early gold finds in the Tambaroora area came from alluvial diggings where gold was panned and sluiced from the creeks of the Turon River valley. The population exploded to over 4,000 in the early 1850s as prospectors surged to a shanty town that sprang up overnight. In time, tradesmen, storekeepers, bankers, clergy, police and publicans arrived in the rapidly growing township to provide miners and their families with supplies and necessary services.

Life on the gold-fields would have been extremely difficult for Sarah and her family in the early years. Pioneer settlers faced a harsh environment and difficult climatic conditions, ranging from very hot dry summer days to freezing, wet winters with occasional snowfalls. Numerous insects and nasties of the Australian bush would have been abundant, an added danger to settlers, particularly those accustomed to town life.

Tambaroora was about 46 miles from the closest town of Bathurst. Access to the area was by horse or on foot. All supplies had to be carried over the hills and down gullies by horse or pack mule as the terrain and stony tracks limited the use of bullock drays. People and livestock walked the same difficult routes. The Barlows would have made that onerous and hazardous journey with small children and whatever possessions they could transport.

Thomas Roberts described James Barlow’s early contribution to Tambaroora.

“At Camp Hill, Tambaroora, he undertook to erect a log-cabin for the police to use as a lock-up. I was told by local residents on a number of occasions that Grandfather was the first person incarcerated in the ‘pen’ on account of visiting one of the 60 local hotels of that period. When I became acquainted with him many years later he was a quiet, harmless old man who, however, occasionally showed signs of a quick temper.

After the pattern of the majority of diggers, he was never very lucky as a miner, though he once had an interest in a claim on the famous Hawkins Hill line of reefs in the 1870s.”

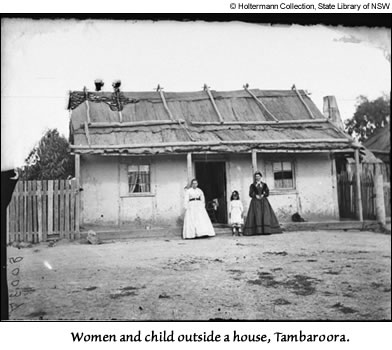

In the 1850s homes of the miners and their families were generally primitive, often little more than canvas tents with strips of bark to support and strengthen and with earth floors. Pioneer women, many of them recent migrants, coped with hard physical toil, impoverished conditions and the perils of an isolated and alien environment. They improvised to clothe their families, sewed or mended clothes in the dim light of candles or a kerosene lamp, had their babies often without assistance of midwives or other women. Infant mortality was very high, young children failed to flourish due to malnutrition and their miner menfolk were exposed to dangerous conditions on the diggings. Fatal mining accidents were common.

Water, always a problem, had to be carried from a small river or creeks. Access to clean drinking water was always difficult in an area where the gold was alluvial, panned from the creeks. Firewood had to be located, chopped and carted to the dwelling, children to be cared for, clothes washed in creeks or water holes, food to be prepared. Food was cooked in camp ovens or billy cans. Wallaby or roo meat, damper and the occasional fish with whatever vegetables could be coaxed from the poor soils were the basic diet for most miners and their families. Basic food supplies consisted of sacks of flour, tea and sugar with other sundries often a luxury. Sanitation was primitive and disease was a constant problem for the population. Outbreaks of diseases such as typhoid, scarlet fever, cholera were common and medical assistance scarce in the early years of the township.

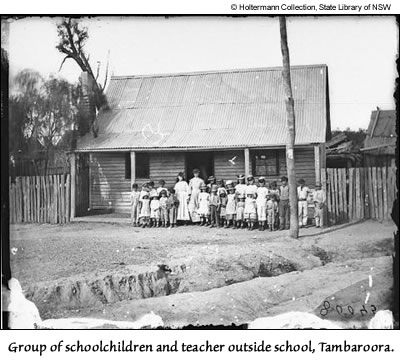

Over the years more substantial dwellings including shops, schools and churches were built.

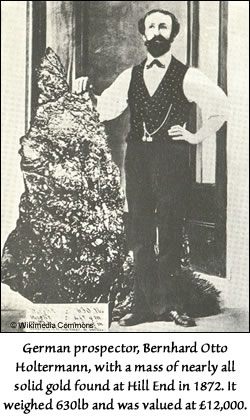

Tambaroora thrived until the 1870s, when very rich reef gold was located in an area about 5 km to the south at the small township of Hill End. Here gold production boomed and as that town expanded to about 9,000 people, Tambaroora began to decline. Today it no longer exists – a once thriving township with over 30 hotels swallowed up by the bush.

Hill End was one of the richest gold producers in NSW and the world until production began to decrease towards the end of the 19th century, when it too lost population and significance. Today it has a population of about 120 and is popular with fossickers, campers and tourists who brave the difficult road access. Some original buildings still stand, many restored and in use. The surrounding landscape is littered with old mine shafts, tunnels and rotted timber mine heads. About 80 photographs, taken from original glass negatives of the 1870s Holtermann Collection held by the State Library of NSW, are erected on sites where various buildings and businesses once stood, and provide a fascinating glimpse into daily life and activities of the 1870s.

James and Sarah lived at Tambaroora for the rest of their lives but James never found his Eldorado.

Thomas Roberts remembered his grandmother Sarah as “ a very religious old lady, who used to wear out bibles, which did not matter much since she knew by heart the passages … she wanted. “

Sarah Barlow was typical of many immigrant pioneering women who overcame tremendous deprivations and challenges to raise their families. She must have been a woman of great inner strength, spirit and determination. I like to think that I inherited some of her qualities through my great grandmother, grandmother and mother.

Their death certificates show that James died in June, 1897, at the age of 86, and Sarah died in December 1908, aged 83. Both were buried in the Hill End – Tambaroora General Cemetery where James had been sexton for some years. The location of their graves is unkown as the markers have disappeared due to the ravages of time and climate. The cemetery is a peaceful place, a clearing in the bush open to sky, sun, the sounds of birds and the smell of eucalypts. It is a long, long way from the fields of Sussex and Kent and the streets of Lancashire. As I wandered there on a sparkling autumn day, I felt very close to my pioneering kin and wondered what they thought of the life they had made in this strange, new land.

Sunny Kate

© Sunny Kate 2009

SOURCES

The Hill End Story, Book 2 by Harry Hodge. 1980 Revised, Hill End Publications

Images from the Holtermann Collection, State Library of NSW are used with the kind permission of the State Library of New South Wales. All enquiries about the images including all requests for copies should be made to the Mitchell Library.