Hand loom weaving is an ancient tradition going back certainly to pre-Roman times. The Chinese were weaving silk into cloth 4000 years ago. We know little of the English methods of weaving until about the 12th or 13th century, when hand loom weaving was a recognised and organised trade.

Hand loom weavers traditionally worked in their homes but a system of cooperation between workers made the process more efficient and less isolating. The history of weaving is well documented and so for this article I am going to concentrate on just one man who was a hand loom weaver.

In 1699, the population of Darwen in Lancashire was 699. Darwen at that time was little more than a village and quite separate from its nearest town, Blackburn, which itself was not much more than a large village with even more remote hamlets on the bleak moors.

Darwen in 1699 consisted largely of hand loom weavers. The work was combined with small scale farming and was little more than a subsistence living. However, during my research into one hand loom weaver I have come to realise that subsistence living does not necessarily mean poverty of spirit or mind.

Timothy Holden (1700-1791) was born in Darwen and was a hand loom weaver all his life. His early life is obscure but there is a note in the baptismal register of Lower Chapel, Darwen, on 22nd July 1700, fining his father, James Holden, for failing to baptise his son Timothy. It is also clear that Timothy received an education, because he could read and write and was a learned scripture scholar.

Timothy married (probably twice, neither marriage has been found) and had nine children. I have found only one child’s baptism and that was in the Lancashire circuit records of the Wesleyan Methodists, but several more children can be assumed to be his from later records, including marriage records and gravestone inscriptions.

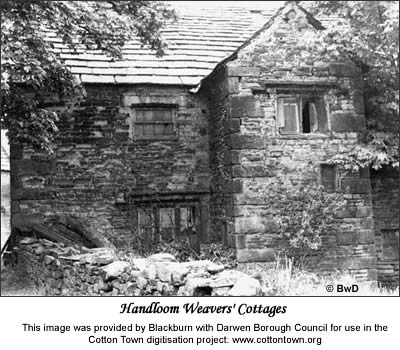

Timothy can be credited with starting a type of factory system for hand loom weavers. Local weavers gathered at his cottage, ‘The Looms’, and worked together, whilst Timothy taught them to read the scriptures.

Weaving was done on large looms, made by hand of course and a loom would be a family’s prized possession, as it was their only means of accessing any cash. The raw yarn was collected from a man called the ‘putter out’, spun by the women and children and then woven into cloth by the men. Every member of the family would be involved in some way. The finished work would either be collected by a ‘chapman’, who would bring them new yarn and pay them, or, in the case of Darwen, the cloth would be taken to the piece market in Blackburn and sold to the putter out. This system was still in operation in the early 1800s and it would seem that the weavers walked to Blackburn with the finished cloth on their backs, a round trip of maybe 15 miles, on rough horse tracks and across inhospitable moorland. Often Darwen was cut off by snow for months on end in the winter.

It was a precarious trade and prices fluctuated daily, but as this was the only cash that most families could earn, the work went on. Cotton cloth was largely unknown in England before the 1700s. Cloth was woven from a mixture of wool and linen and called cotton, possibly because of the slightly raised nap on the finished fabric.

Because of Darwen’s relative remoteness, the church seems to have bothered very little with them. Most were nonconformists, Timothy certainly was and preached his religion to his neighbours. All the families in the village were related through marriage and in common with many other small places, men of the same name were given distinguishing nicknames. Timothy was ‘Old Timothy o’t’ Looms’. The 1841 census records a derelict cottage called ‘The Looms’ at Hoddlesden, near Darwen, and the land on which the cottage stood was Holden land. Timothy and his family lived at ‘Broclehead Farm’ so it would have made sense to turn an unused cottage into a weaving shed for the area.

These were poor families, but they had no masters and little interference from the larger world outside. In this atmosphere of fierce independence, a number of eccentrics flourished and the general intelligence seemed to be high. Timothy’s son, Thomas, became a schoolmaster, as did several grandsons, all in the 1700s when education was not free, nor was it prescribed for the working classes.

Timothy died at the age of 91, at the home of his daughter. His widow died the following year. They had by then, over 100 grandchildren and 30 or so great grandchildren – there were to be many more. Most were hand loom weavers as a matter of necessity.

Hand loom weaving was given a death blow by the emergence of the mills, which started in the late 1780s, then gathered pace over the next 50 years until the whole area was covered with them. Some hand loom weavers struggled on and can be seen as such on the 1851 census, but by 1861, they had virtually disappeared. Many had emigrated to the US, where their skills were still needed – rural farmers and hand loom weavers – but the vast majority had been swallowed into the mills where they were often worked into an early grave. This was a far cry from the ‘factory’ set up in his home by Timothy all those years ago.

This was not only the end of an independent, if poor, way of life, but also the end of the wonderful co-operation of a tight-knit community related by blood and marriage ties and a common interest in each other’s survival. I am left with a sense of strength and decency and simple religious principles.

Timothy was a modest man who went unremarked, except by his own, in his lifetime. He would, I am sure, be amazed to know that people still talk about him more than 300 years after his birth.

Olde Crone Holden

© Olde Crone Holden 2009

SOURCES

Darwen and Its People by JG Shaw 1889.

A History of Blackburn and Surrounding Areas

Spinning the Web: NW Cotton towns