Over the next three issues we will be looking at the Industrial Revolution. This month we are looking at the textile industry and in March we will be looking at transport, with mining and the iron and steel industry to follow in April.

The effects of the Industrial Revolution were more widely felt than in these three areas and it is relevant to every occupation and theme we have featured, or are ever likely to feature, in the magazine. The Industrial Revolution was to transform completely the social and economic map of Britain, as well as every other country it reached.

Up until the 1700s life for our ancestors was much as it had been for centuries. The majority of the population lived in rural areas and worked the land, producing enough food to sustain local need. Goods were produced locally, by hand, in response to local demand, and generations of families lived in the same village.

However, the Industrial Revolution took the economy from a local to a national and international level, replacing man and horse power with machines and uprooting thousands of people from the country to the towns, completely changing their lives and those of their descendants.

It was the development of the steam engine by James Watt, which powered the machines and later the railway locomotives, that laid the path for the Industrial Revolution.

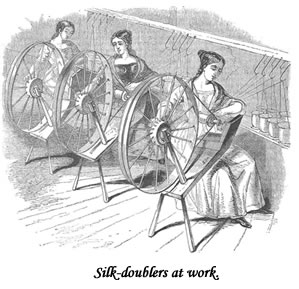

The textile industry was, historically, a ‘cottage industry’. Artisans, as well as their families, worked in their own homes. The raw materials were supplied and the finished products collected and paid for. In the 19th century production was moved to huge mills and factories, employing hundreds of people.

The textile industry was the first to be mechanised, with the invention of the flying shuttle in 1733 increasing the output of the weaver. This, in turn, led to the development of the spinning machine known as the ‘Spinning Jenny’ in 1764, followed by ‘the Spinning Frame’ in 1769 and the ‘Spinning Mule’ in 1779, all in an effort to keep up with the weavers’ ever increasing demand for thread.

The start of the hand loom weavers’ decline came with the invention and development of the power loom. Not only were they far too big to be used in workers’ cottages but they also needed to be near a water supply because they were water-powered, so huge mills were built to accommodate them. The first water-powered cotton mill was built in 1771 in Cromford, Derbyshire, by a number of partners – including Richard Arkwright, the inventor of the ‘Spinning Frame’.

However, it was the development of the steam power looms, with their reliance on coal rather than water, which proved to be the weavers’ death knell.

The skilled weavers and spinners were, understandably, fearful for their livings as they were unable to compete with the output of this new technology. Some, referred to as ‘Luddites’, resorted to rioting and machine breaking but most workers accepted the inevitable and left behind the traditional workplace of their homes to work in the factories – no doubt influenced by the incentive of the provision of workers’ houses, inns and churches.

However, working in the cotton mills was by no means an improvement to their lives, which were now totally controlled by the factory owners. The hours were long and the work was dangerous. Women and children were preferred over men because of the cheapness of their labour. This was long before the introduction of legislation to improve working conditions and reduce working hours, in particular for minors. Their 68-hour weeks were governed by the operation of the machines and by a set of rules, with fines from their pay if they were broken.

The damp, mild weather conditions of North West England provided ideal conditions for the spinning of cotton. Many mills were in Lancashire, with Manchester earning the name ‘Cottonopolis’, where the number of cotton mills reached their peak of 108 in 1853.

In 1835 the French political thinker and historian, Alexis de Tocqueville, penned his experience of Cottonopolis:-

“A thick black smoke covers the city. The sun appears like a disc without any rays. In this semi-daylight 300,000 people work ceaselessly. A thousand noises rise amidst this unending damp and dark labyrinth… the footsteps of a busy crowd, the crunching wheels of machines, the shriek of steam from the boilers, the regular beat of looms, the heavy rumble of carts, these are the only noises from which you can never escape in these dark half-lit streets”

The raw cotton had been brought from India since the 1700s, however by the 1800s this started to be replaced by the cheaper, yet stronger fibres produced by slaves on the cotton plantations of America and the Caribbean.

It was the reliance on this particular source of cotton which led to the Lancashire Cotton Famine of the early 1860s. During the American Civil War the Union blockaded the southern Confederate states of America, stopping the export of cotton. Workers in England suffered hardship, with many relying on relief, as mills closed leaving them unemployed.

Of course cotton wasn’t the only raw material of the textile industry. The domestication of sheep (and goats) goes back centuries and was an important part of the English economy in the medieval period, before it was overtaken by the increased popularity of cotton. Flax was traditionally used to make linen, and the processes for both were revolutionised by the mechanisation of the mills.

Silk, derived from the cocoon of the silk worm, originated in China and came to Europe via the ancient ‘Silk Roads’. European production was concentrated in France and Italy, and it was the French Huguenots, fleeing religious persecution, who brought the process to England in the 17th century. The process was brought into the industrial age with the ‘Punchcard Loom’ in 1775 and the ‘Jacquard Loom’ in 1801, leading to the mass production of silk.

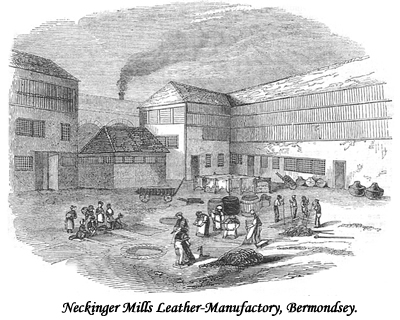

The tanning of animal hides and skins goes back centuries and in London, in the Victorian period, was centred in Bermondsey, which was renowned for its foul smell emanating from the dog excrement used in the tanning process.

The textile industry not only provided employment in processing the raw material but also in professions which used the finished product to create goods, such as tailors, dressmakers, hatters, shoe makers, upholsterers etc. During the 1800s these were just as likely to work from home or in small workshops as in factories.

The mechanisation of the textile industry also led to the development of other industries, such as the chemical industry, with the demand for bleaches and dyes. The engineering industry expanded to build the factories’ huge machinery as well as the sewing machine and needles for commercial, as well as domestic, use.

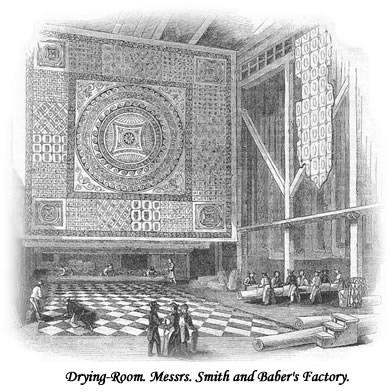

The Great Exhibition of 1851 was an opportunity for the Victorians to show off their achievements in the industrial age, and the textile industry was no exception, with displays of luxury materials, fashions, carpets and tapestries, as well as the most up-to-date equipment.

It was European and American textile production which led the industry right up through the 20th century, especially with the invention of synthetic fibres. However, this went into decline as cheap imports started to arrive from the Far East, and we all know how difficult it is now to find home produced textile products.

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2009

The images in this article are from ‘The Penny Ilustrated Magazine’ and were provided by Roger in Sussex.

Sources

Journeys into the Past – Life during the Industrial Revolution

Further Reading

Manchester Mills – Victorian Textiles, Spinning & Weaving Mills in Manchester

BBC Nation on Film: A Factory Worker’s Lot ~ Conditions in the Mill