Lace was originally made by hand – a slow and intricate process. However, in the 16th century one William Lee from Nottingham invented a mechanical device, the ‘stocking frame’, which paved the way for mechanisation in the textile industry and played a large part in the Industrial Revolution. ‘Framework knitting’, using an adapted version of Lee’s machine, became a widespread cottage industry throughout the East Midlands, and was firmly established in Nottingham by the 18th century.

John Heathcoat made further improvements to the stocking frame, and in 1808 constructed a machine that produced ‘English net’ or ‘bobbinet’, a perfect imitation of handmade pillow-lace. Heathcoat’s invention caused great concern in the lacemaking trade, and in 1816 his factory in Loughborough was attacked by Luddites, believed to be in the pay of Nottingham lacemakers. 55 lace frames were destroyed, and Heathcoat moved his business to Devon. However, his invention was soon adopted by lacemakers in Nottingham, and from then on, the town’s lace industry boomed.

The Mallet family

Henry Mallet, a saddler (nephew of Jonathan Mallet, the army surgeon featured in the January 2009 issue of this magazine: Army Surgeon in Revolutionary America ), was born in Weeford, near Lichfield, Staffordshire, around 1776. The vast majority of his family remained in Lichfield, but Henry moved to Nottingham around 1800, where he founded a dynasty of saddlers and lace manufacturers.

His oldest son, Henry (1804-1873), was apprenticed to Thomas and Francis Braithwaite, hosiers of Nottingham, in 1817. His second son, William, moved to London, where he worked as an umbrella maker until he went bankrupt in 1867, and his brother Henry had to help pay off his creditors. The third son, John, became a saddler and livery stable keeper in Nottingham, while the fourth and fifth sons, Thomas and Christopher, both went into the textile business, Thomas as a lace manufacturer and Christopher as a silk tie manufacturer.

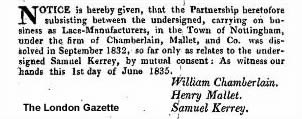

In 1829 Henry junior married Henrietta Chamberlain, the daughter of lace manufacturer William Chamberlain. Until 1831 William was a partner in Shaw & Co of Nottingham with Thomas Shaw and Samuel Kerrey. William Chamberlain took Henry into partnership with him, along with Samuel Kerrey. The 1832 History, Gazetteer, and Directory of Nottinghamshire lists the firm of Chamberlain, Mallet and Co, lace manufacturers, at 9 Stoney Street, Nottingham, in the area which came to be known as ‘The Lace Market’. Samuel Kerrey left the partnership in September 1832.

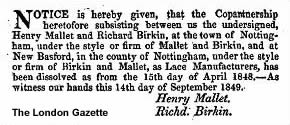

William Chamberlain died in 1845, and Henry went into partnership with lace designer Richard Birkin, who later became Mayor of Nottingham. However, the partnership was short-lived, as it was dissolved in 1848.

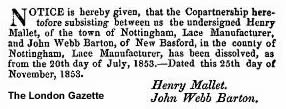

Henry subsequently went into partnership with John Webb Barton, and in 1851 the firm of Mallet and Barton exhibited at ‘The Great Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations’ (more commonly known as ‘The Great Exhibition’) in Paris, and won a prize medal for “Imitation black trimming laces, &c.” Despite the firm’s success at the Great Exhibition, this partnership was also dissolved, in 1853.

Thereafter Henry appears to have continued in business on his own account. In 1853, the Council of the Society of Arts set up a committee to promote industrial training. The committee took evidence from educational establishments, and also sent a circular to leading manufacturers, asking for their views. One of the manufacturers who replied, in a letter printed in Appendix A to the report, was Henry Mallet, who emphasised the importance of practical in addition to theoretical training:-

I beg to acknowledge your communication of 31st of January, and in reply to remark, that having read over the contents to several, both working mechanics and employers, but one feeling pervades the minds of all – that of approval of the plan proposed. On reading over the six suggestions thrown out in your prospectus, I could not but observe that the sixth called forth from each person a decided approval.

We have in Nottingham a school of design, a mechanics’ institute, and an artisans’ library, but in none of them is there taught the elements of industrial instruction. My son, a youth of about eighteen, who is likely to have charge of our factory, and has entered himself a student at the school of design to learn mechanical drawing, can only be taught the science in theory: books, and the teacher (who himself only understands the theoretical part) are the only facilities afforded. It is true, that, like some others, having thus obtained the theory he can, with the assistance of our workmen in our own smith shop, work out some of the principles taught. Yet, this cannot be comparable to what is proposed in the prospectus, viz. a practical training and knowledge of the principles of the sciences on which arts and trades are founded, so as to be able to guide the working artisan.

I have found in my own past experience much of the want of this early scientific training, which would have saved much time, labour and expense, had I possessed it in early life; and therefore feel interested in any movement which will accomplish so desirable an object. I should think the best appropriation of the surplus proceeds of the Great Exhibition, would be to devote it to such an object. I give this opinion as one of the successful competitors in Class 19.

I should imagine that suggestion No. 2 would work well; and No. 3 in connexion with schools of design, where mechanical drawing is already taught theoretically, and where books are already supplied; in addition to which, maps, models, diagrams and apparatus, together with a thoroughly competent master, could not fail to secure a great amount of beneficial results; and as there are already exhibitions periodically of drawings, with a few prizes, the whole of suggestion No. 6 might be carried out in conjunction with them, thereby throwing a considerable additional interest into the whole.

The report of the Committee appointed by the Council of the Society of Arts to inquire into the subject of industrial instruction, 1853, Appendix A

The sixth suggestion made by the Council, which Henry Mallet so heartily approved of, was the institution of a system of prizes or scholarships for the promotion of industrial knowledge, similar to those which already existed in the field of classical education.

The 18 year old son referred to in the letter was Henry’s second son, Henry (1835-1911). He and his younger brother John Thomas (1840-?) both appear to have joined the business, which at some stage changed its name to Henry Mallet & Sons. Their older brother William Henry (1830-1895) seems to have gone into business on his own account. William Henry Mallet appears in the censuses from 1851 onwards as a lace manufacturer, and in the 1881 census is described as “lace manufacturer employing 104 men, 74 women, 38 male and 15 female young persons, and 20 boys”.

In the 1861 census Henry Mallet is described as “silk and cotton lace manufacturer employing 71 men, 180 women, 35 boys, 31 girls”. The description of his occupation in the 1871 census is badly faded, but appears to read “lace manufacturer employing 102 men, 140 women, 30 youths and 70 children”.

Child labour

Child employment was very common at the time, but protests against children’s working conditions were beginning to be made, and one manufacturer who came in for some very public criticism was Henry Mallet.

A series of Factory Acts had been passed from 1802 onwards to regulate working conditions in factories, especially for women and children. The 1833 Act stated that children under 13 years old were to work no more than 9 hours a day and 48 hours a week, but although it applied to textile factories, lacemaking establishments were exempt from its provisions. The 1850 Act stated that children and women could only work in factories between the hours of 6 am and 6 pm in the Summer and 7 am and 7 pm in the Winter, that work was to finish on Saturdays at 2 pm, and that the working week was increased from 58 to 60 hours.

A public meeting of ‘master and operative lacemakers’, called to discuss the possible extension of the Factory Acts to lacemaking factories, was held in Nottingham on 14th January 1860. The meeting was chaired by county magistrate Thomas Broughton Charlton, and speakers included Rev John Montague Valpy, Vicar of St John’s Church, Nottingham, and Henry Mallet.

The meeting was reported in The Times on 16th January 1860:-

THE ADOPTION OF THE FACTORY ACTS IN LACE FACTORIES

An important public meeting of the master and operative lacemakers was held on Saturday evening, the 14th inst., in the Assembly-rooms, Nottingham. Mr. Thomas Broughton Charlton (county magistrate) occupied the chair, and on the platform were the Rev. J. Montagu Valpy, incumbent of St. John Baptist, Nottingham; Messrs. Councillor Cox, Mallett. &c. […]

The chairman then read a number of extracts from a blue-book, showing that many children, 9 or 10 years old, were engaged from perhaps 2, 3 or 4 o’clock in the morning until 10, 11, or 12 o’clock at night, and, indeed, sometimes later.

Mr. MALLETT (a manufacturer) said that these extracts applied to the lace trade 20 years ago; but manufacturers were not in the habit of ill-using the boys, as had been represented in that book.

An OPERATIVE: Things are worse now.

The CHAIRMAN said he must beg to correct Mr. Mallett, as he (the chairman) was only reading statistical facts.

The Rev. J.M. Valpy suggested that if Mr. Mallett had any remarks to make he should do so when the chairman had concluded.

The proceedings of the meeting were widely reported in the press, and the Daily Telegraph’s report of 17th January 1860 described the impassioned speeches made by Mr Charlton and Rev Valpy which were quoted verbatim in the first volume of Das Kapital by Karl Marx, in a chapter entitled “Branches of English Industry without Legal Limits to Exploitation”:-

Mr. Broughton Charlton, county magistrate, declared, as chairman of a meeting held at the Assembly Rooms, Nottingham, on the 14th January, 1860, “that there was an amount of privation and suffering among that portion of the population connected with the lace trade, unknown in other parts of the kingdom, indeed, in the civilised world… Children of nine or ten years are dragged from their squalid beds at two, three, or four o’clock in the morning and compelled to work for a bare subsistence until ten, eleven, or twelve at night, their limbs wearing away, their frames dwindling, their faces whitening, and their humanity absolutely sinking into a stone-like torpor, utterly horrible to contemplate… We are not surprised that Mr. Mallett, or any other manufacturer, should stand forward and protest against discussion…. The system, as the Rev. Montagu Valpy describes it, is one of unmitigated slavery, socially, physically, morally, and spiritually… What can be thought of a town which holds a public meeting to petition that the period of labour for men shall be diminished to eighteen hours a day?”

It was proposed that a petition should be presented to both houses of Parliament in favour of the adoption of the Factory Act in the lace industry, and the resolution was passed by the meeting.

In March 1860 the Earl of Shaftesbury presented Parliament with a petition from the inhabitants of Nottingham and its vicinity, signed by 10,000 people, including merchants, manufacturers, magistrates, clergymen and members of the town council, requesting that lace factories be brought under the operation of the Factory Act, and this provision was finally enacted in 1861.

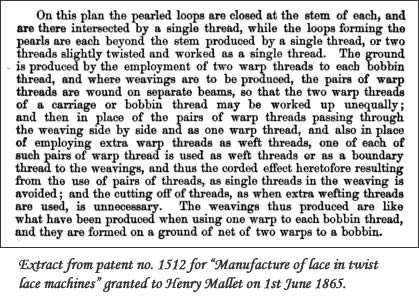

Patents

Henry Mallet and his companies took out numerous patents, including a patent for Valenciennes lace (right).

The death of Henry Mallet

Henry had married into a Baptist family, and became a senior deacon of the Baptist Church at Broad Street, Nottingham. He died in Radford, Nottinghamshire, on 19th January 1873, and the General Baptist Magazine published the following obituary:-

Jan. 18, Henry Mallett, sen. deacon of the church in Broad Street, Nottingham. For nearly two years he had suffered from paralysis. Upright and conscientious as a Christian man, kind and generous as a master, as sunshine itself in the family and among Christian friends, his memory will ever be cherished with love and honour by all who knew him.

Whether Henry was the cruel sweatshop operator suggested by Marx and Rev Valpy or the kind master referred to in his obituary is impossible to tell. Probably the truth falls somewhere between the two; though a devout Baptist he was no doubt a strict taskmaster and saw nothing wrong with employing children, in accordance with the customs of the period.

The closure of Mallet & Sons

After Henry died in 1873, his son Henry junior took over the business, and under his management the firm registered numerous patents in the 1880s and 1890s.

Whether business was declining or Henry felt that the time had come to retire is not known, but Mallet and Sons went into voluntary liquidation on 17th April 1895.

In the 1901 census Henry is shown as a lace agent, while his younger brother John Thomas, who had moved to Surrey with his family, was a clerk in a leather warehouse. Their older brother, William Henry, had died on 24th July 1895. In the 1911 census Henry is shown as living on his own means, so the firm was presumably not insolvent at the time of its closure, but the fact that Henry and John’s occupations were rather more humble in 1901 than the earlier description of ‘lace manufacturer’ does seem to suggest financial problems.

The time capsule

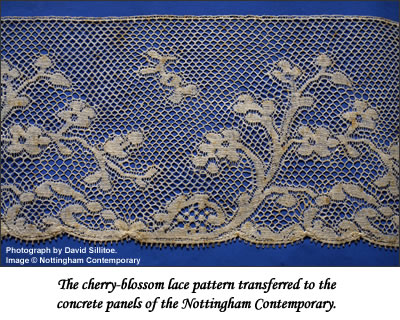

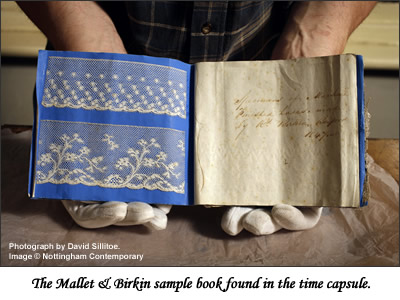

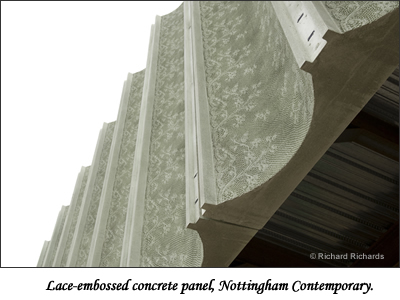

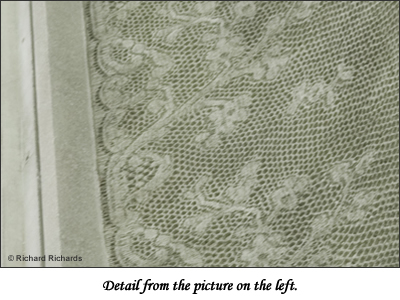

It was recently decided to build an arts centre in Nottingham, known as the ‘Nottingham Contemporary’ (due to open in autumn 2009), and the architects opted to decorate the concrete cladding panels of the building with a lace theme, to celebrate Nottingham’s industrial heritage. The design chosen was based on a sample of lace found in a ‘time capsule’ which had been buried beneath the foundation stone of the former waterworks when it was built in 1847.

The box contained two pairs of gloves, a knitted purse, and a sample book labelled “Mallet and Birkin, lace manufacturers, St Mary’s Gate, Nottingham”.

|  |

Dressing Nottingham’s New Contemporary Arts Centre

So although Henry Mallet died in 1873, his work still lives on today in the gigantic lace-embossed concrete panels of the Nottingham Contemporary.

Mary from Italy

© Mary from Italy 2009

SOURCES and FURTHER READING

The report of the Committee appointed by the Council of the Society of Arts to inquire into the subject of industrial instruction, with the evidence on which the report is founded, published under the sanction of the Council of the Society of Arts, London, Longman, Brown, Green and Longmans, 1853

A History of the Machine-wrought Hosiery and Lace Manufactures, William Felkin, printed by W. Metcalfe, 1867

Subject-matter index of patents applied for and patents granted for the year 1865, Bennet Woodcroft, published by the Patent Office, 1867

Das Kapital, Karl Marx, 1867

The General Baptist Magazine, 1873

A History of the Machine-wrought Hosiery and Lace Manufactures, William Felkin, printed by W. Metcalfe, 1867

A Brief History of Hosiery and Lacemaking in Nottingham

Childhood Transformed: Working-class Children in Nineteenth-century England, Eric Hopkins, Manchester University Press ND, 1994