Honiton (pronounced “Hun-i-ton”) is a market town nestled in the Otter Valley in East Devon. Wool manufacture flourished in the area in the reign of Henry VII, and Honiton was reputedly the first town in which serges were made, but the industry declined during the 19th century. The wool industry was replaced in importance by the lacemaking industry.

What is Honiton Lace?

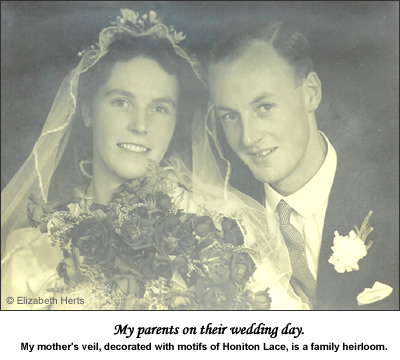

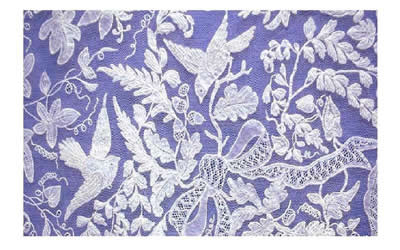

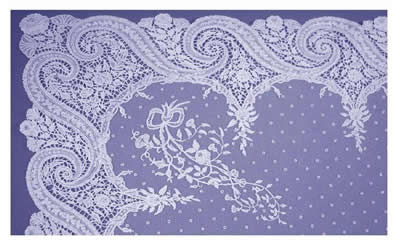

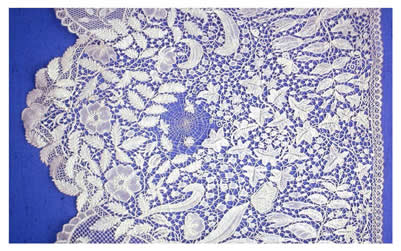

Honiton lace is a miniature form of weaving and is made using fine thread wound onto pairs of bobbins made of bone or wood, hence the name ‘bobbin lace’. A pattern is pricked into heavy waxed card, which is subsequently pinned onto a pillow stuffed with barley straw. Very fine pins are inserted into the holes of the pattern and threads are weaved back and forth in order to build up the lace. When the structure is complete, the pins are removed and the finished motif is joined to other motifs to create a larger item, such as lace collars and cuffs, the edgings for handkerchiefs, shawls, tablecloths and bedspreads. Many wedding veils were made using Honiton lace. Indeed, my own wedding veil, a family heirloom, had motifs of Honiton lace.

The History of Honiton Lace

It is believed that lacemaking began in East Devon in the latter part of the 16th century, but documentary evidence can only be found from the 17th century. However, not all or even most Honiton lace was made in Honiton. It was called Honiton lace because it was sent to London via the Honiton stagecoach, and later on by the Honiton train.

It is still debated whether Honiton lace was an English invention or whether it was brought to England by Flemish refugees escaping religious persecution. During the Commonwealth period ornament in dress was frowned upon but, with the return of the monarchy under Charles II, the popularity of lace soared. English lace, and thus Honiton lace, faced stiff competition from Belgium, Holland and France. Heavy duties were imposed on lace imported from Continental Europe but this only served to increase its desirability. It is suggested that at this time Flemish lace workers were encouraged to come to Honiton and teach their craft but there is no firm evidence for this.

In St Michael’s churchyard, on the hilltop overlooking Honiton, a tombstone from 1617 states that James Rodge, a bone lace seller in Honiton, gave £100 to the poor of the town. This indicates that a good living could be made from the sale of lace. In 1630 historian Thomas Westcote records that there was an abundance of bone lace in the town.

During the reigns of George II and George III the quality of English lace improved and Honiton lace became famous throughout Europe and highly sought after, with detached flower sprays replacing geometric patterns. Honiton lace flourished until the advent of machine-made lace in about 1808, when demand for net ground plummeted. Ironically, a large factory at Tiverton, 17 miles away, employed about 1500 workers involved in the production of machine-made net. Of course, the production of Honiton lace is extremely labour-intensive and requires a considerable degree of skill. Honiton Lace became famous throughout Europe but there was also fierce competition from other lacemaking centres. Flemish lace makers were based in cities and production was a very organised activity. The designers were highly skilled and studied at government-run colleges. The finished products were also of extremely high quality.

Royal patronage became increasingly important for the survival of Honiton lacemaking. When Queen Victoria married Prince Albert in 1840 the original design for her veil specified Brussels lace, but Victoria insisted that English lace be used. The order was sent to Tuckers of Branscombe, one of the largest employers of lace makers. When the Princess Royal, Victoria, was christened the gown was made of Honiton lace lined with white satin. It is still in use today.

The industry survived by the use of machine-made net onto which the lace sprigs or motifs were appliquéd. This greatly reduced labour costs, but the Honiton lacemaking industry never regained its previous superiority.

For a child growing up in the 1950s and 1960s Honiton lace was already largely a memory of the past. Lacemaking classes were still held, and are today, but lacemaking had become a hobby rather than job.

The Manufacturing Hierarchy

There was a complicated hierarchy in the lace industry.

The merchants or manufacturers organised the trade. It was they who took the orders and placed the work, and also marketed the products. They employed designers, lace-makers and finishers, and they provided the lacemakers with patterns and threads.

The lacemakers worked from home and provided their own pillows, bobbins and pins. Men used to work as lacemakers in the early days of the industry (around 1700), as earnings for lacemaking were on a par with those of an agricultural labourer. However, a century later, only women and girls were working as lacemakers. The sewers and finishers were responsible for assembling the sprigs of lace and they often lived on the manufacturers’ premises. They were better paid than the lacemakers themselves.

The Truck System

The truck system essentially meant that the lace workers were paid in part by goods. The manufacturer ran a grocery or general shop and the lacemakers were paid half in money and half in goods. However, they were often paid just in goods, which led to abuses, and full value was frequently not given. Furthermore, the goods given to the lacemakers were not necessarily what they wanted. Although the truck system was abolished by law in 1779, it remained in practice well into the nineteenth century.

“Thus two loaves of bread and ½ lb of butter form part of a common weekly allowance for girls. The object of this is to prevent the people from selling the goods again and so getting any ready money, which would enable them to be independent, and by anything they might wish for at other shops where they could get it better.”

Mrs Wheeler of Sidbury

Lace Schools

Small children, often as young as four years of age, were sent to ‘lace schools’, where they primarily learnt lacemaking skills but were sometimes given a rudimentary education. The Education Act of 1870 eventually killed off most of the lace schools.

The Importance of Lacemaking to the Local Economy – Some Statistics

“The Lace Maker’s Memorandum” of 1698 states that there were 4,695 lacemakers in East Devon and that they made up 23% of the population. 1,341 of them were in Honiton. In 1780, there were about 2,500 lace workers in the town, but by 1820 this number had fallen to about 300. After that we have to turn to the census records of 1841 and 1851 for further statistics.

In 1841 the number of lacemakers in East Devon as a whole has dropped to 531, a reduction of nearly 89% compared to 1698. In Branscombe, on the coast, only 107 people were employed as lacemakers (out of a population of nearly 1,000). There was something of a boom after 1841, with Branscombe having 296 lacemakers out of a population of 906 people in 1851.

The 1841 census clearly shows that most of the lacemakers were the women folk of farm labourers and other labourers. This extra money was a welcome and necessary addition to the low wages that the men brought home.

Honiton Lace Today

By 1940, no-one was making Honiton lace for a living. Although Honiton lace is not commercially produced nowadays, the craft of lacemaking survives and the skills required are still being passed on to the next generation. Allhallows Museum in Honiton has an impressive display of Honiton lace, and it also runs regular lacemaking classes.

Elizabeth Herts

© Elizabeth Herts 2009

The images of the examples of Honiton Lace have been kindly supplied by the Allhallows Museum of Lace and Local Antiquities in Honiton.

The History of the Honiton Lace Industry by H.J. Yallop, University of Exeter Press, 1992

Honiton An Old Devon Market Town by M. Edmunds West Country Books

Lace, its Origin and History by Samuel L. Goldenburg Brenato’s New York 1904 (not in copyright)

The Branscombe Lace-Makers Edited by Barbara Farquharson & Joan Doern. The Branscombe Project 2002