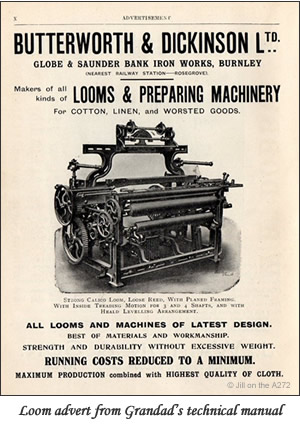

For my childhood holidays we stayed with my grandparents in Nelson, Lancashire, in their ‘two up two down’ terraced house every summer. Grandad, Albert Bannister, had been a weaver, as had his father Sam (1872-1950), grandfather Henry (1844-1888) and great grandfather William (1810-1862), and one year he arranged a visit to a cotton mill for us for something to do. I was about 10 and it was one of the noisiest experiences I have ever had, as it was the first time I had ever been unable to hear what someone was saying, even though they were shouting by my ear. If you are familiar with the comic female Lancashire characters of Les Dawson’s Cissie and Ada you will know that their lip movements were exaggerated when speaking – exactly as the mill workers were doing that day.

As a souvenir I was given a couple of old shuttles, lined with rabbit fur to prevent the thread looping as it unravelled, and some oddments of fabric. Mavis, the lady showing us round had an enormous bruise on her upper arm caused by a shuttle flying out of the loom, Granny remembered someone who lost an eye in the same manner.

Years later, the shuttle re-emerged when we sorted out my parents’ house following my mother’s death. It went home with me and hangs on my wall in honour of my weaving ancestors. Then, as I watched the ‘Who Do You Think You Are?’ television programme featuring Bill Oddie with them talking about “kissing the shuttle”, which involved sucking the thread thought the tiny hole and the illnesses caused by inhalation of fibres, I had an instant flashback to that mill visit, where I saw exactly that action performed and the air and machinery full of fluff.

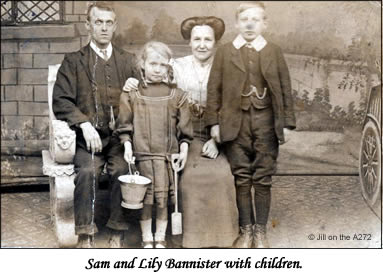

I knew my ‘Bannisters’ from Trawden and my ‘Nutters’ from Briercliffe had been both hand loom and power loom weavers as far back as 1841, beacause my great aunt had researched her grandfathers’ family trees, but it was only when I began my own research that I found that my great grandmother Lily Abbott’s ancestors had a background both in tailoring and weaving.

I researched my Atkinson and Abbott ancestors in Barnoldswick, which is now in Lancashire but was then in Yorkshire and is known locally as Barlick. My great x4 grandfather, Thomas Atkinson, was born in Gisburn in 1803, and followed his father’s trade of tailor. Five children were born to him and his wife in Barnoldswick, Broughton and William P Atkinson becoming tailors while the girls, Rachel (my great x3 grandmother) and her sisters, Leah and Mary were power loom weavers at the time of the 1851 census.

Then my cousin, Gordon Abbott, with whom I got in touch through Genes Reunited suggested that I look at the One Guy From Barlick web site. There I found the ‘Lancashire Textile Project’ and the wonderful resources which are the work of Stanley Challenger Graham. I was lost for hours in the transcripts of interviews with mill workers of my grandfather’s generation, and the many photographs of weaving and all the processes that go with it, all of which is available to download. Also on the website there is Stanley’s transcript of a manuscript history of Old Barlick by a WP Atkinson, and to my delight I realised that it had been written around 1914-5 by William Parkinson Atkinson (1840-1927), a man with an interest in local history and a lively sense of humour, and the brother of my great x3 grandmother, Rachel Atkinson.

Here the day to day life of a weaving town sprang to life. He describes how hand looms were in the bedrooms, and the weavers’ children would be helping out by winding the bobbins. He mentions with great disapproval, no doubt passed on to him by his uncles who employed hand loom weavers, the ‘ronge dealers’, to whom the home working hand loom weavers could sell the leftover warp threads, having been delivered more than they needed to allow for mistakes in weaving or misfortune while winding the bobbins. Up to 1842 most of the weaving was done on hand looms, work was either brought by a ‘putter out’, or some weavers would collect and return their work on their backs to Colne.

Recalling reminiscences of his father, William talks of how the weavers’ cottages had no back doors, or plastered ceilings, there was bare woodwork throughout. Windows opened with a casement rather than a sash. Floors had flagstones which were scattered with sand, and the fireplace would have a wide chimney to allow the sweep to get up inside.

Water had to be fetched from the town well or the beck, and William recalls, as a boy, being sent for milk with a ‘back tin’ strapped to his back and returning with 6 quarts, some of which sloshed down his neck. It is worth quoting him in full on the diet of the time:-

“We may thus understand that skimmed milk formed one of the most useful household commodities and was used along with meal or flour or rice or sago or for baking purposes, or even at supper time when a large piece of oatcake, after its being well toasted and broken into some milk, formed a nice and light supper and no after effects were feared or nightmares experienced. There were two kinds or degrees or ways of making either meal or flour porridge. One kind of favourite mess namely ‘Hasty Pudding’. Flour also contributed to the making of the Yorkshire and numerous other kinds of puddings and pancakes. Meal was sometimes used for making ‘stirabout’ in the frying-pan after the bacon was taken out and a little warm water added to the bacon drip, this last named beverage called stirabout has gone out of fashion. A large amount of meal was required for baking the indispensable food called oatcake. The so-called back-stone was a thick iron plate arranged on brickwork with fire grate underneath. Most of the farmers, and also some of the larger families possessed a back-stone. There were however several public bake-houses for oatcake, such as old Polly Slater’s, Old Betty Simpson’s and others, where folk could take their five or ten pounds of meal and fetch back the same a day or two afterwards, and all ready for hanging up on the bread-fleak to dry. All this privilege cost only a few coppers. Such bread as was in use then was three times the thickness of the present day oatcake sold by hawkers. Potatoes and other vegetables, chiefly home grown, were cheap. Butchers meat were also cheap and the poor folks’ joint was usually boiled, and a basin of broth with plenty of oatcake or dumplings in the same, this formed the first course, afterwards came the beef and vegetables. The hung beef, or bacon, where such luxuries could be afforded, were much appreciated, as was occasionally a good fat old hen in its season. For these and all other mercies, old Barlickers were truly thankful yea!”

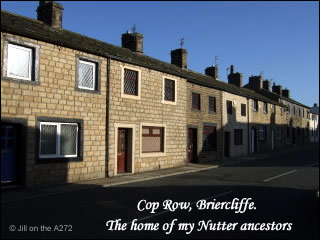

I had already come across the Lancashire oatcake, as in 1851 my ancestor James Heys at Cop Row, Briercliffe, was a hand loom weaver and grocer while his wife Nancy was an oatcake baker. Members of the Briercliife Society supplied me with various recipes; oatcakes could be eaten fresh and soft or hung on a rack to dry and go hard like crispbread. ‘Stew and hard’ was a well known dish.

It is all down to William that I have anecdotes of the family. How wonderful it has been to have them spring alive from the formal pages of the census. His father old Tommy Atkinson the tailor is described sitting on the table by the window sewing at a local farm earning 18d a day plus food and witnessing the milk deliverer with his milk tin on his back accidentally pull the tablecloth off the kitchen table; old Tommy catching an eel in the beck; and being Hon. Sec. of the bogus ‘Hen Pecked Club’, said to include all married men compelled to perform household duties!

He mentions his uncles, James Dugdale and George Livsey, both weavers who also employed other hand loom weavers. George brought the first ‘Lucifer’ matches into Barnoldswick around 1843 which caused a “flutter of wonderment and curiosity in the town”, as well as enabling me to discover that George’s wife was Margaret Broughton, sister of my Tommy Atkinson’s wife Ann Broughton. While Eleanor Broughton married James Dugdale in 1839, so I have been able to discover from the marriage certificate that Eleanor’s father’s name and therefore my Ann’s too was Stephen Broughton, a mason. His mother was Ann Oddie so who knows, I may have a connection with Bill!

WP Atkinson also preserved the diary of his friend Richard Ryley, a weaver who began writing in 1862 during the ‘Cotton Famine’ caused by the blockading of cotton exports from southern Confederate state ports by the Unionists during the American Civil War. This led to the hardship of unemployment, or half days work for Richard. He was able to supplement his income by busking around local villages and inns, although he did not always break even. He records his finances, and experiences when applying for relief from the Relieving Officer. He was in poor health and mentions the kindness of friends, family and his employer who paid for him to see a doctor, but the diary ends on 11th June 1864, shortly before his death at the age of 43, leaving a wife and two small children. The original diary is at Skipton museum, and a transcript is on the ‘One Guy from Barlick’ website.

I can think of no better way of ending than in the words of William Parkinson Atkinson, tailor and hatter of Barnoldswick:-

“This having now been accomplished in a simple and homely manner, and with the kindest regards to all those ancestor’s names [which] may have been used as a name to illustrate what was intended. Thereby I sincerely trust that this little work will be accepted in the same friendly spirit in which it has been written.”

Jill on the A272

© Jill on the A272 2009

Sources and Acknowledgments

Gordon Abbott

Stanley Challenger Graham

David B, member of Family Tree Forum, for the photo of Cop Row