WHEELWRIGHTS

In the days when the nation relied on horse drawn transport, particularly before the era of the railways, wheelwrights played an important role in keeping the country moving by making and repairing wheels, carts and wagons. Some built carriages, landaus and coaches, right through from the construction of the wheels and the bodywork, to the upholstery, finished paint work and the coat of arms.

The wheelwright would work closely with the blacksmith, often in the same premises. The era of motorised transport brought the demise of their way of life, and many wheelwright and blacksmith’s shops were converted into the first garages.

In the coaching era, it was very common for a wheelwright to operate from an inn on a coaching route, where the travellers would stop overnight and the coach undergo repairs. You will often see them in trade directories described as a ‘wheelwright and beer retailer’.

The rural wheelwright’s work would come mainly from the agricultural community; building dung carts, farm wagons, dog carts, jigs etc, as well as making ploughs and harrows. They were highly skilled carpenters and could quite easily turn their hands to making anything from a piece of furniture to a child’s toy.

The start of the whole process of construction began with the wheelwright going into the local woods to choose which of the newly felled trees he wanted to purchase. Mindful of their intended purpose, he would select them for their width and shape. An experienced wheelwright would know the best woods to buy from, as even the soil could effect the quality of the timber.

The wheelwright used oak, ash, elm and beech. Oak was best felled by the foresters in the late spring and early summer, as the sap at this time allowed the bark to be stripped down easily, whilst ash, elm and beech was best felled in the winter.

Once the trees had been selected, they were loaded onto a timber cart and delivered to the wheelwright’s premises by the timber carters. The wheelwright would mark out the timbers where he wanted them to be cut into planks, felloe blocks, spokes and hub stocks (more about these later), in preparation for the sawyers who would come in the winter and open up the trees in the saw pit in the yard.

The felled blocks of ash, elm, oak or beech required further shaping by the wheelwright whilst still green, and the oak spokes and elm hub stocks were left as blocks. All would be piled up in stacks, with spacers between them, kept off the ground and undercover, so that they could be dried out or ‘seasoned’. During the following autumn/early winter they would be transferred into the indoor timber store and left to continue seasoning for ‘a year for every inch of thickness’, which generally was around 5-6 years, and the date would be chalked on the wood to identify it. During this time it still needed to be constantly checked, with any mildew or fungus brushed away.

In this way the wheelwright’s latest supply of timber was laid idle for years, whilst he worked on wood which he had purchased many years before. As the wheelwright’s business became more commercialised in the late 19th century, the middle men of the timber yards came into being, sourcing the trees, preparing the timber and seasoning it.

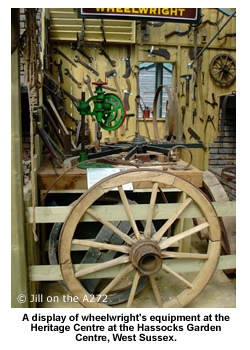

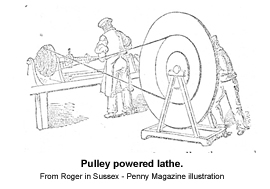

A wheelwright would work at their bench in their workshop, with tools such as an axe, adze, plain, shave, saw, chisel, hammer and mallet. A grindstone in the yard was used to sharpen their tools. Smaller pieces of wood would be crafted at their bench, whilst larger pieces would be worked on in the saw pit. A pulley powered lathe was used to shape the wheel hubs.

Their business was very much a local one, with wheels, carts and wagons designed for their intended use and for the environment in which they would be used.

A wheelwright’s apprenticeship lasted for around five years. Patterns for the different parts of the wheels, carts, wagons, carriages and coaches were handed down from master to apprentice and from father to son. The only measure an experienced wheelwright would have needed was their ‘rule of thumb’.

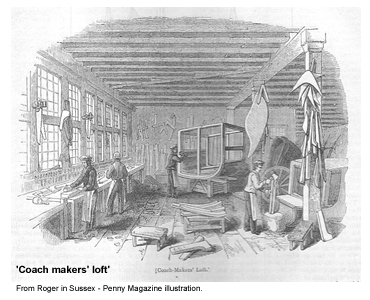

It would take several months to build a cart, wagon, carriage or coach, with each part following the same traditional pattern, cut to size in the saw pit, and plained and bevelled at the wheelwright’s bench.

While the construction of a cart would begin with a framework known as the ‘bottom timbers’, wagons would start with a hind and fore undercarriage joined together with a pole, and it was from this that the axles, floor, sides and raves were built. Carriages and coaches were built in a similar way.

The wheels were traditionally made in the shape of a dish, to not only withstand the downward pressure of the load, but also the sideways motion created by the horses pulling it.

First the spokes were shaped from the seasoned spoke blocks from the timber store, using an axe, draw shave, smoothing plane, a hollow bladed plane called a ‘jarvis’ and a spoke shave. Next came the felloe blocks, which were crafted with a plane, adze and axe into the curved segments or ‘felloes’, which form the outside edge of the wheel. Then came the stock blocks from the timber store, which were shaped into wheel hubs on the lathe. They were then marked out for the holes where the spokes would be placed, always an even number, with each felloe taking two spokes.

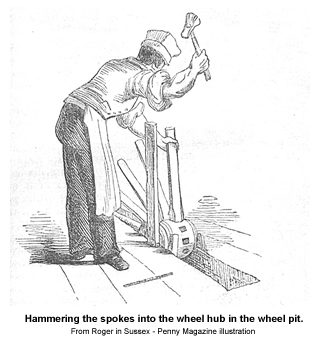

The hub was then placed in the wheel pit and the spoke holes bored. The spokes would then be taped into place with a sledge hammer, with the other end of the spoke ‘tongued’ with a tenon saw, chisel and mallet in readiness for the felloe.

The hub, with the spokes attached, was then fixed onto a wheel block, and the felloes, with two bore holes in each, fixed to the end of the spokes, and each felloe joined together with a oak dowel.

It was at this point in the process that the wheelwright required the assistance of the blacksmith to make the iron hoop tyres for the wheels. Traditionally these would have been small strips of iron called ‘strakes’, which were only placed over the felloe joins and not continuous around the wheel. However by the mid to late 19th century these were replaced by hoop tyres, the process of which is explained here.

The blacksmith would cut off a strip of iron, around the same length as the circumference of the wooden wheel, bend it into a circular shape in a tyre bender, then heat it up on the forge until it was hot enough for him to hammer and weld the two ends together on his anvil and make the holes for the nails.

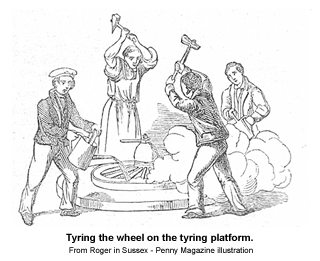

The hoop tyres were then taken outside to the yard, where the wheelwright had either an upright brick oven or a fire on the ground, fuelled with the waste wood from the saw pit, and the tyres would be placed inside to heat up.

The wooden wheel was then fixed down onto the tyring platform, and wooden barrels filled with water in preparation for the tyring.

Once the hoop tyre was red hot, it was pulled out of the fire with tongs and a tool called a ‘dog’, thrown down on the ground, then placed quickly onto the waiting wheel using the tongs and dogs, and positioned, pulled, hammered and nailed into place, as it sparked and scotched the wood. Once it was fixed in place the barrels of water were poured over the wheel, as the red hot tyre hissed, steamed and contracted as it cooled, pulling the whole structure of the wheel together.

The traditional strake and the iron on the hubs, otherwise known as the ‘stock bonds’ were prepared and fitted in the same way.

The wheels would then be fixed onto the axles, and the whole wagon, cart or carriage then shaved to reduce the weight and provide a good finish ready for painting. The blacksmith would make any additional ironwork, including decorative pieces, which he would prepare with a file and punch.

Apart from building carts, wagons and carriages, the wheelwright would also repair existing ones. This was called ‘jobbing work’, whereby parts would be replaced due to wear, tear or damage, and the wheels re-greased.

The farmers brought their carts, wagons and equipment to the wheelwright for repair in the springtime, after storing them away all winter. The heat of the summer provided the wheelwright with more work, as it heated up and loosened the iron tyres, which in turn weakened the structure of the wheel. If parts needed replacing then the wheel would have to be taken apart and remade.

Once receiving word of a breakdown, the wheelwright would go out in his own wagon, with his tools, and attend to it at the roadside.

However, the days of the traditional wheelwright were gradually drawing to a close. By the 1880s, farm equipment such as ploughs, harrows, hoes and pitch forks were being made of iron, instead of wood, and mass produced in the factories of the Midlands

As the supply of food went from a local to a national and an international level, wagons were needed for different purposes and expected to be lighter and to run faster on the now much improved roads. Orders for trade vans from butchers and bakers were now replacing the work from the farmers. Even ready made parts, such as lighter wheels, were being imported from America and the wheelwright was expected to stock these.

Parts of the wagons and carts were now being made of iron instead of wood, such as the axles and the ‘strouters’, which were used to stop the load pushing out the sides. Other parts were adapted, such as the new tipping iron which replaced the old wooden back bumper.

Where once the wheelwright served the needs and requirements of the local community, they were now competing with others much further afield. Their craft had become commercialised.

Prices, which were once fixed according to a job, had to be competitive, with many undercutting the other and taking on work with little or no profit, just to get the business. They had to produce quotations for work, which were very difficult to cost when the wood had been purchased several years before.

The wheelwright had to adapt. His traditional tools were replaced with new labour saving equipment such as gas engine powered saws, lathes, drills and grindstones. He became a machine hand rather than a craftsman.

While the First World War provided more work, it also hastened the era of motorised transport and the motor car, making the work of the wheelwright and blacksmith obsolete. Many learnt the necessary skills and converted their workshops to garages, but others, mainly the older generation, felt that it was time to sell up and move on.

Their craft is now mainly confined to restoration work and living museums, a poignant reminder of these highly skilled craftsman who lived the wood they crafted.

BLACKSMITHS

If you look at an old map of any town or village, you would see the words ‘smithy’ marked on it. This was the blacksmith’s shop.

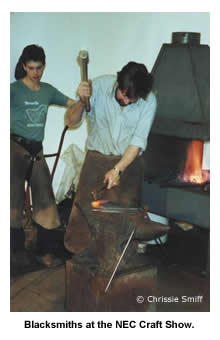

Glancing inside the dimly lit smithy, you would have seen the coal burning on the forge, and the blacksmith, wearing his leather apron to protect him from the heat, hammering at a piece of red hot iron or steel on his anvil, sending sparks flying into the air.

Horses would have been brought into an area of the smithy called the ‘travis’ to be shod. A blacksmith who specialised in shoeing horses and in horse care was known as a farrier.

The blacksmith worked with the black metals of iron and steel, so called because of the layer of oxide which forms on their surface during heating. The term ‘smith’ derives from the word ‘smite’, which means to ‘hit’, so a blacksmith is a person who smites black metal.

While modern blacksmiths use oxyacetylene or a blowtorch, the only source of heat in the traditional smithy would have been the forge, with the larger and busier ones having several burning all day. So you can imagine how hot these places would have been, especially in the heat of the summer. These workshops needed to be dimly lit because the blacksmiths needed to be able to see when the metal glowed yellow/orange, and therefore soft enough to bend, hammer and cut into shape.

In the case of welding, the pieces of metal would have been heated on the forge until they glowed yellow/white and almost molten, then quickly transferred over to the anvil where they were hammered together.

As well as working closely with the wheelwrights making the iron parts for the wheels, carts, wagons etc, and making and fitting the horseshoes, they would also make wrought iron gates, grills, railings, light fixtures, furniture, sculpture, tools, agricultural implements such as pitchforks, spades, hoes etc, decorative and religious items, as well as cooking utensils.

They were highly skilled craftsman, who even made their own tools, such as punches, drills, hand chisels, tongs, pincers and files.

But like the wheelwright, by the early 20th century the blacksmith’s craft was in decline. Iron and steel items were being mass produced much cheaply in the factories of the Midlands, and motorised transport was replacing horse power, so that the services of the local smithy were no longer in demand.

OTHER SMITHS

Arrowsmith This is a person who makes arrow heads. They are also known as fletchers and their craft is called fletching. In medieval times, the village of Fletching in East Sussex was a major producer of bows and arrows, many of which were used at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415.

Bladesmith A blacksmith who makes knives, swords, daggers and other blades. They also craft wood for the handles and leather for the sheaths. Some specialise – a swordsmith in swords, a scythesmith in scythes, a sicklesmith in sickles, razorsmith in razors etc.

Coppersmith A person who uses copper in an artistic form to make items such as jewellery, sculptures, plates and cookware, jugs, vases, trays, frames, rose bowls, cigarette boxes, tobacco jars, overmantels, fenders on fireplaces, decorative panels, challenge shields, tea and coffee pots, awnings, light fixtures, fountains, range hoods, stills and artwork. A coppersmith was also known as a brownsmith and as a redsmith, because of the colour of the metal worked with.

Fendersmith A person employed to clean and repair the metal fenders in front of fireplaces in mansions, fine estates, or castles. In this archaic profession, the same person is usually also responsible for lighting and keeping the fire contained within the fireplace. Few fendersmiths exist today, but can be found in places like Windsor Castle.

Goldsmith A metalworker who specialises in working with gold and other precious metals. Traditionally they would have made flatware, platters, goblets, decorative and serviceable utensils, ceremonial and religious items. However in modern times they are more likely to specialise in the making of jewellery.

Silversmith Whilst a goldsmith specialises in gold, a silversmith specialises in silver, crafting items such as cutlery, bowls, plates, cups, candlesticks, armour, vases and other decorative items, as well as jewellery. However, some do work with gold, copper, steel and brass and therefore the two occupations are very much linked and were usually part of the same guild. A silversmith is also known as a brightsmith.

Gunsmith A person who repairs, modifies, designs, or builds firearms to factory or customer specifications. They need to possess mechanical, metalworking and woodworking skills, and be knowledgeable in ballistics and chemistry, as well as in the laws governing firearms.

Locksmith Locksmithing is the assembly and designing of locks and their respective keys

Pewtersmith Pewter is a metal alloy, mostly made up of tin, with the remainder consisting of copper and antimony, acting as hardeners, with the addition of lead for the lower grades of pewter, which has a bluish tint. The use of pewter was common from the middle ages to make tableware until it was replaced by porcelain and glass in the 18th and 19th centuries. The modern pewtersmith is more likely to make decorative items such as statuettes and ornaments.

Whitesmith A craftsman who works with white metal, usually tin, also referred to as a tinsmith, tinner or tinplate worker. The process of tinplating began in the 1600s.

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2008