It used to be extremely disconcerting to walk into a bank in the early 70s and to be asked by the teller if you were related to “the Lewcock who wrote those books”, with the emphasis on those. At that time Francis James Lewcock’s books on banking were still required reading for banking exams. All I really knew about him was that he had written the books, but when I came across the Times Online, I found that there was far more to his life than that.

Francis James (Frank) was born on the 17th July 1897, the son of James Austin and Amy Lewcock née Reed. James was a clerk/accountant and was the eldest son of a printer who has already appeared in the magazine in In the genes? and Skeleton by marriage?. Presumably through the printing connections, Frank was educated at the Stationer’s Company School in Hornsey as was his father and then his own older sons. He was obviously bright, winning a school prize in 1907. Tucked inside the book which he won are copies of the examinations which he took – I can’t imagine even the brightest 10 year olds I have taught getting very far with them these days! In 1911 the family were living in Stanhope Gardens, Haringey, and James was working as a municipal accountant for Tottenham Urban District Council. When Frank left school he went to work as a clerk for the London and Provincial Bank, which was later to become part of Barclays Bank.

At the age of 17 years and three months, in November 1914, he enlisted as a private in the London Scottish (Reserve Battalion) of the 14th London Regiment; interestingly his Medical Inspection Report gives his ‘Apparent age’ as 19 years and three months. He was transferred for Officer Training to the Inns of Court Officers Training Corps in May 1915. He was discharged from there, on appointment to a commission as a 2nd Lieutenant in the Royal Field Artillery with the 1st Northumbrian Brigade, in the following October. He was promoted to Lieutenant in June 1916 when he was sent to the front. When the war was over, he joined the Disposal Board of the Ministry of Munitions in Cologne. He was disembodied [sic] in May 1920 but continued to work for the Ministry as a civilian for a short time.

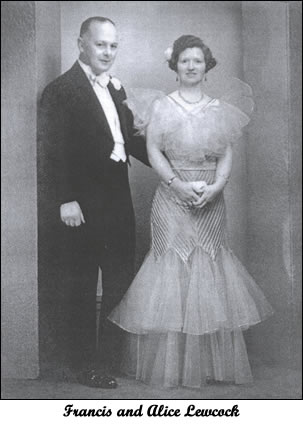

While in Cologne, he met his wife, Alice Bradley, who was working for the Ministry of Munitions as a secretary, and they were married late in 1920.

After his discharge from the army he returned to work for Barclays. In October 1920, the first reference to him appears in ‘The Times’ in a legal case entitled ‘The Extent Of A House Agent’s Authority’. There are also references in The Times Archives to him giving at least two radio broadcasts, a 20 minute talk on ‘Finance’ on LEEDS-BRADFORD in May, 1926 and in 1928 he gave two broadcasts to Secondary Schools: ‘How industry is financed’ and ‘How they raise permanent money’. He also lectured to the Institute of Bankers.

By 1926 he was working at a branch of Barclays Bank in Otley Road, Leeds. In February 1927 the first of many letters to The Times appears. He wrote on a variety of topics, not always financial, including the length of BBC programmes, who finances the British film industry, the dirge like manner of poetry recitations on the BBC, how to pay Customs and Excise the duty on celluloid dolls (that one is very funny), getting telephones installed, bank architecture and so on throughout the 1930s. There must be many more as there are replies and responses to his letters which don’t come up on the search. I wonder if he wrote to the newspaper continually and these are just a selection of what was published.

In 1930 he became a member of the Chartered Institute of Secretaries. In 1931, Frank published the first of those two books on banking, ‘The Securities Clerk in a Branch Bank’ and in 1934, ‘The organization and management of a branch bank’. They were both published by Sir Isaac Pitman & Sons Limited and were in print in several editions for many years.

Frank was obviously not content with just being a bank clerk and had aspirations to be a writer. He started up several newsletters, not always successfully, which could well have been the cause of him being made bankrupt. In December 1933, The Gazette reports “That Banking Publications Limited … be voluntarily be wound by the Members; and that Mr F. R. Tufft …. be and is hereby appointed liquidator” F. Lewcock, Chairman. Francis filed for bankruptcy that month and the family, by then they had five children, moved back down south to the London area. The bankruptcy case must then have dragged on for a long time, as there are still references to it in The Gazette in 1937 with tiny payments of as little as a halfpenny still being demanded by the Official Receiver. He was editing ‘Branch Banking’ in 1936 and in 1939, the Gazette reports that The Watergate Publishing Company Ltd. was wound up in January 1939 by F. Lewcock, Chairman.

Later, he started publishing ‘Background’ a newsletter which he describes as “A private survey of industrial and financial affairs of political significance”. This newsletter was the cause of him being sued for libel, in 1946, by Brendan Bracken and the Financial Times, which was covered in The Times. He lost the case.

In 1937 he became a member of the Institute of Journalists and in 1938 he describes himself as a financial journalist. Also in 1937, The Times carried an announcement that Mr. Francis Lewcock had been appointed Secretary of the Unit Trusts Association. On the masthead of ‘The Background’ he also lists himself as holding the Silver Medal in Banking, The Royal Society of Arts and as being Prizeman in Stock Exchange Practice, London Chamber of Commerce.

From his letters one can get a very good idea of his political leanings. I am told that he was very much a supporter of Churchill and very definitely not a Socialist. In fact my brother has recently found him on Google Books, so he is planning a trip to The British Library to see if he is just quoted in the book, ‘Fellow travellers of the Right: British enthusiasts for Nazi Germany, 1933-9’ by Richard Griffiths, or has written an article.

The topics in the letters change slightly in the later 1930s and reflect what was going in politically and financially at the time e.g. ‘Farming Credit’, ‘Working-Class Savings’, ‘Firms And Slumps: The Downward Spiral’, ‘BBC Accounts’, ‘Standard Of Living In Germany: Working-Class Prosperity’ – this one generated some argument in the column. Then in August 1939, he wrote about ‘The Lost Apostrophe’ on a road sign. In September of that year he was complaining about ‘The Great White Rabbit: Cost Of The Ministry Of Information’.

In 1937, he took his wife and two oldest sons on a visit to Germany about which he duly wrote in the Letters column on their return. I have been contacted by somebody whose mother had found a postcard album. This eventually turned out to be one which Frank and Alice had sent to their youngest children while they were in Germany – I am looking forward to receiving that. (I never did hear any more about this album, which was a great shame as my aunt and uncle would have liked to have seen it again.)

In his army records there is correspondence from 1936 about him offering to re-enlist in the Territorial Army suggesting that he could still do it, “even at thirty nine years old”. During the war he was part of the Home Guard, manning an anti aircraft battery in Hyde Park.

Francis died in January 1949 before I was born, so I never met him. I was always interested in what little I knew about him especially as I was often told I looked like him, although I always thought that was a bit odd as a small child, as he had no hair in the few pictures I saw around. Being able to follow much of his life through The Times Digital Archive has been fascinating and I have been able to discover a surprising amount about a fascinating person.

Caroline

© Caroline 2009