The chances are that many of our ancestors were involved in the smuggling trade whether or not they lived on or near the coast. From drinking a cup of tea or glass of brandy, wearing a silk waistcoat or playing a game of cards or even lighting a candle, they may well have acquired them illegally. They might have been involved in bringing the goods in by sea or in transporting them inland to their final destination.

They may have served in a regiment of Light Dragoons or as members of the Coast Guard, served on board the Royal Navy Cutters or just turned a blind eye or ear to nocturnal sounds of horses.

Rudyard Kipling’s poem, A Smuggler’s Song, probably means that most of us have a romantic view of the smuggler and his trade, but in fact they were ruthless men who terrorised the coastal regions of Britain especially in the South East. Some of the most notorious of them operated in the Chichester area as in the article, Were you born in Yapton?

Murray Lachlan Young reads ‘The Smugglers Song’ by Rudyard Kipling

Peter Dawson singing “The Smuggler’s Song”

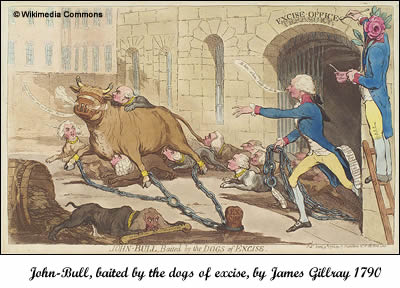

Customs and Excise Duty

Until the 13th century, when the first permanent customs system was established in England, trade in and out of England was free of taxation. English raw wool exports were a significant source of income to the English crown, which from 1275 imposed an export tax on wool called the “Great Custom” in order to protect the weaving trade. The result was that there was over production of wool and the price of wool became too low for the farmers to make a decent profit, so the answer was to smuggle the wool over to the Continent where English wool was in great demand. The illegal trade began in the sheep areas of the Romney marches of Kent, the smugglers being known as Owlers.

Later restrictions, such as the exporting of cannon during the Spanish War, Cornish tin or Cumbrian graphite meant that a lively trade in smuggling developed around the coastline of Britain. However, it was the embargo on the wool trade on the downs and marshes of South East England where there was the greatest flouting of the regulations. It was made illegal to export wool from other than designated ports and from 1662, wool smuggling was made a capital offence. By the beginning of the 18th century, it was estimated that 150,000 packs of wool a year were being shipped out illegally within days of shearing.

There were two types of taxation which were the cause of smuggling, customs and excise. Originally, the term customs meant any customary payments or dues of any kind (for example, to the king, or a bishop, or the church), but this later became restricted to duties payable to the king on the import or export of goods and especially wool. To start with, the duties were quite low, but as the Hundred Years War went on, the taxes were continually raised in order to create revenue to pay for the troops and fighting.

Excise duties are inland duties levied on articles at the time of their manufacture, basically as a tax on domestic consumption. During the Civil War, additional revenue was raised by imposing a new tax, Excise Duty, on goods manufactured in the country, such as candles and beer. Ten years later, it was reduced to just cover chocolate, coffee, tea, beer, cider and spirits. However, after 1688 it was progressively widened to include other essentials such as salt, leather, paper, home produced spirits and soap. The separation of the two taxes meant nothing to the impoverished agricultural labourers and fishermen since all they knew was that what they needed to buy became more expensive as the amount taken in taxes grew and shrank according to the needs of the government to finance the wars with France. Many of them turned to smuggling as a way to improve their income since the high rates of duty on tea, wine, sprits and other luxuries coming from Europe meant that the smuggling trade was highly lucrative. With the double taxation of customs and excise, many commodities could cost up to four times the smugglers’ asking price so there was a ready market from all walks of life.

Under the nova custuma in 1275, Collectors of Customs were appointed by Royal patent and soon after, ‘custodes custumae’ were appointed in certain ports to take direct charge of the collection of customs for the crown. Geoffrey Chaucer, Thomas Paine, Robert Burns and Richard Whittington aka Dick Whittington were all customs officers.

Geoffrey Chaucer obtained the very substantial job of Comptroller of the Customs for the port of London in 1374. He must have been suited for the role as he continued in it for twelve years, a long time in such a post at that period.

Thomas Paine, author of “The Rights of Man”, became an excise officer in Grantham, Lincolnshire in December 1762. In August 1764, he was transferred to Alford, at a salary of £50 per annum. In 1765, he was fired as an Excise Officer for “claiming to have inspected goods he did not inspect.” In 1766, he requested his reinstatement from the Board of Excise, which they granted the next day – upon vacancy. In 1767, he was appointed to a position in Grampound, Cornwall; subsequently, he asked to leave this post to await a vacancy. On February 19, 1768, he was appointed to Lewes, East Sussex. From 1772 to 1773, Paine joined excise officers asking Parliament for better pay and working conditions, publishing, in summer of 1772, The Case of the Officers of Excise, a twenty-one-page article, and his first political work, spending the London winter distributing the 4,000 copies printed to the Parliament and others. In spring of 1774, he was fired from the excise service for being absent from his post without permission. He emigrated from England to America later that year. Wikipedia: Thomas Paine

Scottish poet, Robert Burns trained as an exciseman and was appointed to duties in Customs and Excise in 1789.

In 1643 a Board of Excise was established by the Long Parliament, to organize the collection of duties in London and the provinces. In 1823, an act of Parliament replaced the separate boards of excise for England and Wales, Scotland and Ireland with a single Board of Excise covering the entire United Kingdom. In 1849, the Board of Excise combined with the Board of Stamps and Taxes to become the Board of Inland Revenue. The Customs and Excise Services were amalgamated from 1909, and were administered by the Board of Customs and Excise and became known as Her Majesty’s Customs and Excise.

Customs Officials

Initially the Customs Service was only there to collect the duties at the ports, and not to prevent smuggling. Their job was limited to collecting taxes for the legitimate trade. The head of the personnel at each port was the Collector. His deputy was the Comptroller. Other roles were that of the Coastwaiter, who was responsible for vessels from home ports, the Landwaiter who supervised the unloading of ships from foreign ports and the Tide Surveyor, or Tidewaiter, who was responsible for rummaging (searching) vessels anchored in port. Merry Monty Montgomery tells the story of Charles Buvck, a tidewaiter, in Turncoat in this month’s issue.

Smugglers “were opportunists, taking advantage of a demand for heavily-taxed luxury goods and the state’s almost total inability to collect those taxes.” From ‘Smugglers’ Britain’. It was necessary to patrol the coastline and landing places and so The Landguard of Riding Officers was established on the south coast in 1690 around the Romney Marsh area. By the Georgian era the system had spread to cover the entire country. They were literally customs officers on horseback who carried swords and pistols and patrolled a stretch of coast between 4 and 12 miles in length. They were expected to buy, care for and accommodate their own horses. Usually local men, they were very unpopular as they would be seen as traitors. Although forbidden to accept fees or gratuities, unscrupulous ones would turn a ‘blind eye’ in return for a share of the profits.

Their role was to “apprehend the smugglers and seize the contraband goods, to meet and correspond with the other riding officers either in person or by letter, and to find out if there were any smuggled goods upon the coast, or landed, and to get the best information regarding this booty, and to acquaint the Officers of the Customs all over the shire.” Each port would appoint a Riding Surveyor to co-ordinate the officers under his command.

Excise Officials

The Excisemen were a separate body from the customs officials and had more powers, including the right of entry to search private dwellings. They were more widely spread; like the customs service, they maintained a force of officers in ports and coastal regions but they also had bases in the smaller villages. Their work was similar to that of the Riding Officers. Although even less popular than the Customs officials they received a generous salary which may have made up for it. The Gauger was responsible for measuring spirits and calculating duty.

The Military

The role of the Army was very important in keeping law and order before there were established police forces. Dragoons, light cavalry regiments, would be stationed in major towns and cities to support the local magistrates, the local Yeomanry and County Militia in any large scale civil unrest and smuggling.

Every maritime county would have a regiment stationed there, whose role would be to support the Customs and Excise Officers. Local and national newspapers would report the troop movements:

“General Elliott’s regiment of Light Dragoons will march to York immediately after the review on Wimbledon Common, as mentioned in our paper of Monday last.” Independent Chronicle- April 1770.

“Orders are given for General Elliot’s regiment of Light Dragoons, now quartered in Yorkshire, to march up to town to relieve General Burgoyne’s regiment now on duty at St James, which is ordered into quarters.” Middlesex Journal or Chronicle of Liberty – April 1771.

”Tomorrow Gen. Elliot’s regiment of light dragoons will be reviewed by his Majesty after which they will march for the coast of Sussex, where they will be quartered for the summer.” Morning Herald and Daily Advertiser – May 1781.

“Lord Harcourt’s Dragoons have the Sussex duty. Chichester is to be their headquarters.” World – June 1789.

[If you have any military ancestors, it is worth spending the time searching old newspapers as you may be able to track their movements around the country.]

By the late 1700s, the government were fighting an unequal battle with the smugglers; organised gangs controlled the coastal regions and the government forces were heavily outnumbered both at land and at sea. The wars with the American colonies in 1776 meant that they needed to raise even more revenue and they decided to make a serious attempt at the prevention of smuggling.

At sea

In 1680 Revenue Cutters were launched to patrol the coast and excise men employed to board ships and search for contraband. In 1809 the ‘Preventive Waterguard‘ was formed to operate in coastal waters. They were based in Watch Houses around the coast and boat crews patrolled their allotted stretch of coast each night. So at this time there was a triple defence line for would-be smugglers to pass: at sea the Preventive cruisers, inshore the boats of the Waterguard and ashore the Riding Officers.

In 1816 the control of the Revenue cutters passed to the Admiralty and in 1817 the Royal Naval Coast Blockade for the Prevention of Smuggling was created, under “Flogging Joey” McCulloch’s command, on the Kent coastline between North Foreland and Dungeness which supplemented the existing defences. The blockade was later extended north to Sheerness and west to Southampton between 1818 and 1824. Guard houses were built around the coastline about four miles apart and manned during the night by parties of men landed from the Royal Naval vessels employed in the prevention of smuggling. These men would have to guard about a mile of the coastline with five men on duty at a time. They were volunteers; they could not have local connections and would serve for three years. In the year ending 5th January 1821, there were 1,276 employed in the service.

The title ‘The Coastguard’ Service came into operation on 15th January 1822 and in 1831 the ‘Coast Blockade’ was absorbed into the new Coastguard Service. This new service employed nearly 6,700 men. Coastguards served on ships and on shore. Those men on shore were posted away from their home for fear of collusion and/or collaboration with smugglers. Coastguard Stations were designed and equipped with living quarters for married men as well as single.

Hansard records that on 2nd August 1887, Mr. Norris asked the First Lord of the Admiralty, “For what number of men the Coastguard station at Felpham, on the coast of Sussex, was constructed; how many are now stationed there, and what duties they perform; if he will state the average number of sailors engaged on Coastguard duty in the United Kingdom; under what Regulations appointments are made to this service, both as to officers and men; and, if the pay of all ranks is the same as on service afloat?”

The First Sea Lord, Lord George Hamilton, replied “The Coastguard station at Felpham was constructed to accommodate one officer and 15 men. It is at present occupied by one officer and 10 men, whose duties are to watch the coast for the suppression of smuggling and for the protection of revenue generally. They also look out for wrecks and protect fisheries. There are about 3,500 men in the force, which is recruited from the Royal Navy by men who volunteer for this service. The pay is not identical with that of the Service afloat, as an allowance for subsistence is given in lieu of provisions; but it is practically the same. “

In 1881, there were 11 men and their families listed at the Coastguard station in Felpham, described as coastguard men or boatmen. Genuki has a very detailed listing of British Coastguards from 1841 to 1901 from which you can see how often they moved around the country.

Systematic smuggling eventually came under control not only through the determination of the Coastguard service, but also because Britain adopted a free-trade policy that reduced import duties to realistic levels so that by the end of the 1850s, smuggling on such a large scale was virtually non-existant.

Caroline

© Caroline 2009

SOURCES and FURTHER READING

Flogging Joey’s Warriors by John Douch. Crabwell Publications/Buckland Publications Ltd. 1985

Smuggling in Kent and Sussex 1700-1840 by Mary Waugh. Countryside Books 1985.

The Lawless Coast: Smuggling, Anarchy and Murder in North Norfolk from the 1780s by Neil Holmes. Larks Press. 2008.

King’s Cutters and Smugglers 1700-1855 by E. Keble Chatterton.

An old gate of England by Arthur Granville Bradley. 1918.

Your Archives: East Blockade References

Smuggling in and around Burton Bradstock

The Burney Collection: 17th and 18th Century Newspapers. Available online from some County Library Services.

Cornwall Smugglers: Excise / Revenue Men and Coast Guard

TNA Research Guide : Coastguard