When William and Mary came to the throne in 1689, after James II went into exile, the Government was in debt and certain City merchants agreed to raise money to lend the government £1,200,000, on permanent loan with guaranteed interest.

The twenty-six subscribers were incorporated as ‘The Governor and Company of the Bank of England’ by Royal Charter, and the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street has been in business ever since as the banker for the Government of the day.

The Bank was nationalised after the Second World War in 1946 but regained its independence in 1997. (There is a short history of the bank and its present day functions on Bank of England )

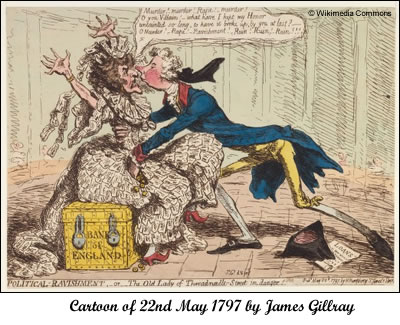

The website for the Bank says that the Old Lady of Threadneedle Street is the nickname given to the Bank of England after a cartoon of 22nd May 1797 by James Gillray which shows the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, ‘attacking’ an old lady sitting on a gold trunk labelled the Bank of England. The Old Lady is yelling, “Rape”, and it was a protest against the introduction of paper money to replace coins.

Herbert de Fraine, in ‘Servant of this House; Life in the Old Bank of England’, suggests that the nickname came from the foundation of the bank in 1694 and the sign hanging over the first office taken from the original seal which had the figure of Britannia sitting and looking at a bank of money on it, which showed the porters and delivery men who could not read where to go, and which they probably christened the Old Lady. The Bank moved to Threadneedle Street permanently in 1734.

For the first few months, the bank was in Mercer’s Hall in Cheapside, but this was too small to handle all the people who came and it was transferred to Grocer’s Hall. There was a staff of nineteen, “a secretary, a sollicitor[sic], a first accomptant [sic] and a first cashier”, with ten tellers and two doorkeepers. Because of the danger of fire, “noe business was to be done after dandle-light”. Later the tellers became ‘In-tellers’ and ‘Out tellers’ and this remained their designations into the twentieth century. In a sense the Bank was a gigantic pawn-shop; the first Bye-laws stated, “That all goods and merchandise pawned unto this corporation and not redeemed at the time agreed upon or within three months afterwards should be sold att a Publick Sale by Inch of Candle”. That is to the person bidding when the candle went out.

Although there were several crises in the early years, the charter was renewed in 1713 and the careful foundations meant the Bank was eventually a profitable enterprise, able to pay clerks what was thought a reasonable wage for the time. However, they had to give a surety of from £500 to £5000, depending on their post, and to take an oath of secrecy and some needed second jobs in the evenings to support their families. On the whole, the clerks had enviable jobs, although there were rules against drinking at work, reading the newspaper or smoking, let alone theatre going or betting, and there are reports of bad behaviour, drunkenness and fighting from time to time.

Nevertheless the business continued to grow; the first premises the bank actually owned were built on the site of the house of the first Governor, Sir John Houblon, and perhaps gave rise to the way the staff always referred to ‘the House’ rather than the Bank or even the Office, while the Directors held their meetings in ‘the Parlour’.

The bank has always had several divisions or sections of work but these have changed over the centuries, and it now has two main purposes, monetary stability and financial stability. The first is perhaps the best known to the general public. This includes the banking service offered to the High Street banks who manage the accounts for saving one’s salary, paying bills, using cheques or credit or debit cards. In the eighteenth century the Bank became the banker’s bank which meant it had to keep enough gold reserves as security against the notes issued by the private banks. It held the actual gold ingots, together with the bags of silver coins and foreign coins in the Bullion Office where giant scales checked the weight of the metal. While modern ways of security, weighing and accounting have been established, the Bank still holds reserves in actual metal; some on behalf on the Government (the Treasury) and some on behalf of its customers, that is itself.

The Bank has been issuing banknotes for over 300 years but they have changed over the years. At first they were simply hand written receipts for deposits, but they became a means of exchange as they promised to pay the bearer on demand not simply the original seller. Gradually these notes were issued only for a fixed amount, at first for £50 but lesser values were brought in and in 1914 notes for ten shillings and one pound were issued. In the nineteenth century the government gave the bank sole right to issue bank notes in England. At first the banknotes were printed in the general offices, but new printing works were opened in 1920 in the old St Luke’s Hospital for Lunatics (which gave scope for many jokes). This continued as the Bank’s printing works until the 1950s when the operation was moved to Essex. The bank sold its printing operations in 2002, but the Bank of England still sees to the design, issue, circulation and eventual destruction of the notes, and as we now know is instrumental in ‘quantitative easing’ or in having more notes printed to ease a problem of liquidity.

The Bank also printed and issued stock certificates and one section was devoted to keeping these up to date and paying out the dividends on the due dates. This was done by cash payment in the nineteenth century, unless a customer specifically asked for a warrant for payment to be sent to them, but the Old Lady did not like this and preferred to deal in cash, although she eventually caught up with the times and now of course all payments can be done ‘on-line’ if one wishes. In the 1914-1918 war the Bank issued War Bonds and King George V printed off the first Nomination War Bond in 1917. (He pulled the lever which started the machine).

In maintaining financial stability the Bank is involved in operations in the financial markets and particularly in managing the country’s foreign exchange reserves which involves gathering intelligence and specialist risk management to a greater extent than in the past.

Another important modern function of the Bank is in conducting monetary analysis to support the Monetary Policy Committee, building and analysing various economic models to try and forecast movements in the economy, to suggest trends in inflation for the Treasury to aid the Chancellor in budgeting, and of course the Bank is responsible for setting interest rates to try and meet the inflation targets set by the Chancellor.

See Herbert de Fraine in Servant of this house for much fascinating detail of both the social life and the conditions of work for an employee of the Bank from 1886 to 1931.

Marjorie Dawn

© Marjorie Dawn 2009

SOURCES

Servant of this House; Life in the Old Bank of England by H.G.de Fraine.. Constable. 1960

The St Luke’s Printing Works of the Bank of England by H.G.de Fraine. Stanley Beaumont Chamberlain 1931