John Horniman was born on 4th December 1803 at Reading in Berkshire. He was the fifth and last child of Thomas Horniman and his wife, Hannah Brewerton.

Thomas and Hannah were accepted into membership of the Society of Friends, or Quakers, a few years after their marriage and so John and his elder brother, Robert were sent to the Quaker school, Ackworth in Yorkshire for their education.

Thomas Horniman was an umbrella maker and had a shop on King’s Street in Reading, so whilst this family were not perhaps poor, they certainly were not rich either.

In 1817 Thomas Horniman died but, unfortunately, I have not been able to find a will for him.

Two years later, Thomas’ widow, Hannah, married my 4x great grandfather, Thomas Smith from Witney in Oxfordshire, at the Reading Quaker Meeting House. As a young man Thomas had also been a convert to Quakerism and had also been a widower for two years. Thomas Smith came to live at King’s Street in Reading where he and Hannah continued with the umbrella shop, Thomas having previously been a hat maker all his life.

At this time the Society of Friends did not allow their membership to marry non-Quakers. The membership did not incorporate a large percentage of the population, so perhaps it’s not surprising that Hannah’s sons, Robert and John Horniman, were soon married to two of Thomas Smith’s daughters, Hannah and Ann, in 1821 and 1825 respectively.

When these couples married, Robert and John Horniman were both in the grocery business, Robert being at various times a cheesemonger, biscuit baker and confectioner or grocer, and John a cheesefactor or grocer. Unfortunately, Robert’s career was checked by his early death in 1832, aged 38, when he and two of his four children were killed by cholera within a few days of each other.

John Horniman’s business was set to flourish, and within the space of a few years he had grocer’s shops in several towns across the south of England, and so, in about 1842/3 he decided to take a partner into the business. His partner was his brother-in-law, my 3x great grandfather, Job Smith, who had recently lost his wife.

John and Job decided to set up a new business venture in the Isle of Wight – selling tea in pre-weighed ready made packets. Things went well for John and Job for a while as people who purchased their new product found that is was not adulterated with other substances as tea was often found to be. However, the business only ticked along at a steady rate and eventually the partnership failed as Job had remarried and wanted to try a new life in America, to which he sailed in 1854.

A little later John had a lucky break with his tea business as during the late 1850’s the Lancet magazine produced a series of articles regarding its campaign against the adulteration of food. The editor, Thomas Wakely, arranged for food samples from various sources to be tested for their purity. Horniman’s Tea was extremely highly praised as passing the tests in “triumphant fashion”! This particular article and the subsequent publicity for the Horniman name resulted in huge growth for the Horniman Tea Company. Wakely’s campaign resulted in the passing of the Food and Drugs Act in 1860.

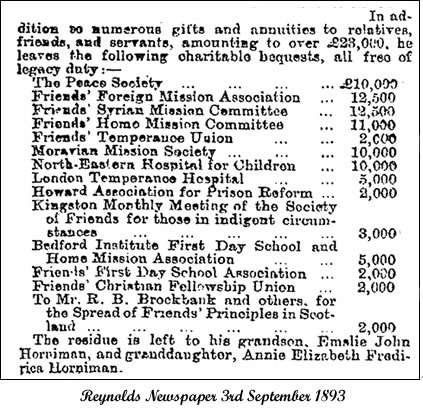

So, from around 1860 until John Horniman’s death, the business went from strength to strength. So much so that when John died in August 1893 his estate was valued at £313,775 10s 4d. The list of bequests in his will is extremely long and details some 36 of John relatives and friends. He also gave a great deal of money to various causes which are listed in Reynolds’s Newspaper on September 3rd, 1893.

However, not everything in life runs smoothly, even if you are very rich financially. John and his wife had six children, but only two lived to adulthood. Of the four who died, one succumbed to phthisis as a teenager, one to diphtheria as a baby and the other two died before civil registration began, so I have been unable to establish a cause of death.

The two surviving sons were destined to inherit their father’s business and the company was styled ‘W H and F J Horniman’ from 1869. Unfortunately only one son, Frederick John Horniman, was able to take an active part in the business. It took me a long time to establish what happened to William Henry Horniman, the elder of the two by four years. In 1841, 1851 and 1861 he was with his parents on the census returns. In 1851 he is recorded as a tea dealer aged 19 and in 1861 a commercial clerk aged 29. By 1871 he was living separately to his parents, though not far away, with two female servants.

We often have to remind ourselves that the census is just a ‘snapshot’ and can mask events in the lives of those recorded. This is certainly the case for William Horniman as the previous year he had been admitted to The Retreat (see Bedford Pierce), a progressive Quaker ‘hospital’ which dealt with mental illness in a more caring fashion than most, if not all, other establishments at that time. William was admitted again in 1871, 1873 and 1876 each time for a period of months, but the last time for over three years. In 1880 William was transferred to Wonford House Asylum in Heavitree, Devon, where he remained for the 1881 census, where his condition was described as ‘lunatic’. Upon admission to Wonford William was described as 39 years of age, a Quaker and a merchant. I’m not sure how long William was at Wonford House Asylum or why he was transferred there, but by 1890 the wheels had been put in motion to have William certified as a lunatic.

On 28th November 1890 an Inquisition of Lunacy found him to be of unsound mind when he was examined at his new home, Ashelden House in Torquay, Devon.

Once examined and found officially to be a lunatic, the normal process was for the person to be committed to a secure place, which for most would be a lunatic asylum. In such a place the patient would be restrained or imprisoned in order to keep them away from the general public. In fact, William was not committed to an asylum as his family was wealthy enough to have him cared for at Ashelden House. In 1891 he is recorded as head of household and a lunatic living on own means, but also in the house was one Walter H Oldfield, aged 39, who is described as ‘companion’ to the head of house and whose occupation is ‘Person in Charge’.

I’m sure all this was devastating for William’s parents. In 1891 the census shows they were probably visiting their son as they were staying near to his home and some one hundred miles from their own; no mean feat for a couple aged 87 and 91. It may be that at this time they were arranging new accommodation for their son as the house where they were staying in 1891 was where William eventually died in 1900.

Between 1891 and his death, William’s main preoccupation was to re-write his will which he had written on 5th November 1869. Of course there was no way any will made after he had been certified would be accepted, but he was determined and on one occasion managed to ‘escape’ his home and make his way to London with the intention of visiting a solicitor to put his affairs in order.

William died in February 1900 and his original will was proved on 26th March 1900, the executors being William’s brother Frederick and his late father, John. The majority of William’s estate, valued at approximately £185,000, was bequeathed to his parents, of whom only his mother, Ann, survived. She outlived her elder son by just five months, dying at her home in Croydon aged 100 years and four months.

William’s brother and former business partner, Frederick John Horniman, died in 1906. His son, Emslie John Horniman (1863-1932) was a director of the tea business and also an M.P. for Chelsea for many years. In 1911 he laid out nearly an acre of land in a poor part of Chelsea as a public garden and presented it to the London County Council. Today this is called ‘Emslie Horniman’s Pleasance’ at Bosworth Road, London W10. It was whilst Emslie John was a director of the tea company that it was bought out by J Lyons & Co in 1918. However, the Hornimans remained directors of the firm for several more decades.

Merry Monty Montgomery

© Merry Monty Montgomery 2009

SOURCES

Biographies: Friends Library in Euston Road, London

Annie Horniman (John’s granddaughter) papers: John Rylands University Library

The Horniman Museum, Forest Hill, London

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]