My great great grandfather, Abraham Isaac Guttentag, was born on 18th April 1834 in Ketric, Poland (then part of Russia), and died on 22nd March 1914 in Moses and Solomon’s Almshouse, Mile End, in the east end of London. He was buried in the Plashet Cemetery, East Ham.

Abraham was the son of Chayim David Guttentag and his wife Mariem. Chayim, a tailor, had been born in 1801 and died before Abraham was five, on 10th February 1839, aged 38. I’ve not been able to find out when Abraham arrived in England but he first appears on the 1861 census, living with his wife Esther and baby son Hyam David in Court Street, Whitechapel. At that time he was a ‘cap maker’.

Abraham and Esther had eight children and all of their sons changed their names after Abraham’s naturalisation which was finalised in July 1872. Abraham changed the family’s surname to Rose.

His children were:

Hyam David born 1861 – became Alfred

Miriam born 1862 who died young

Isaac born 1865 – became Arthur

Solomon born 1866 – became Charles

Jacob born 1868 – became John

Miriam Rebecca born 1870

Lydia born 1872, my great grandmother

Cordelia 1874

Abraham started his own business of hat manufacturing in 1868, and moved to the Minories in the City of London in 1873. Business was good and increased every year. In 1883, he changed its name to A. Rose and Co. In the early to mid 1880s, Abraham concentrated on the manufacturing end of the business while his two eldest sons assisted him, Alfred (Hyam) in the ‘counting-house’ and Arthur (Isaac) ‘travelled’, presumably as a salesman.

Abraham had held an account at the Whitechapel branch of the Central Bank of London for many years. The bank discounted his trade bills under an arrangement where he was to keep an agreed balance in his current account and leave a certain percentage of the discounts with them (this type of agreement is still used by banks in dealing with bills of exchange). The agreement was re-signed when the company’s name changed in 1883 and from that time, the business was principally conducted by Abraham’s eldest son, Alfred.

The first sign of trouble was the following year. On December 19th, 1884, a bill discounted by the bank and presented by them for payment was dishonoured as a forgery, the same day that a company cheque was presented for payment. The bank manager was dubious about the signature on the cheque and sent for Abraham who said the signature was his, but at the request of the manager, he agreed to give a fresh signature for the bank records. The bank manager showed Abraham all of the cheques signed by him which they had in their possession at the time and Abraham stated that they were genuine.

Over the period of the next couple of months, bills were discounted to the value of several thousand pounds and cheques subsequently drawn against them. But, three months later in March 1885, the same thing happened and another bill was dishonoured as a forgery. This caused the bank to ‘make enquiries’ regarding the other acceptances held by them on discount. They discovered that of the ₤5,015 worth of bills they held, ₤4,860 were forgeries. Abraham professed ignorance of the transactions and advised the bank that a large number of the cheques drawn on his company were forgeries. His son, Alfred was no longer in the country.

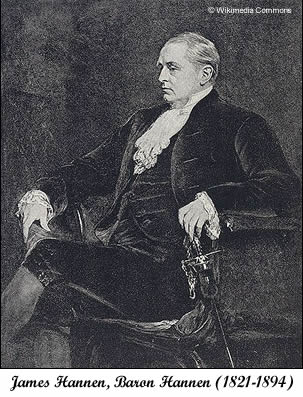

The Central Bank of London sued A. Rose and Company to recover the money it had lost as a result of the forgeries, an amount of ₤2,862, and the case was heard before Sir James Hannen.

Sir James was the son of a London merchant, educated at St. Paul’s School and Heidelberg University and he had been called to the bar in 1848. He was appointed as a judge 20 years later and created a Law Lord (Baron Hannen, of Burdock in the county of Sussex) in 1891. An article in the Tuapeka Times from New Zealand dated October 23rd, 1889 (from the New York Sun) reporting on another case, describes Judge Hannen as, “habitually patient, and even kind to fatherliness, where witnesses are timid or inapt” but “his temper is found very near the surface with the witness who shows a disposition to being uncandid”.

The newspaper report of Abraham Rose’s trial indicates that, “Mr. Evans, the manager of the Whitechapel branch of the plaintiff bank… stated that he believed the drafts of the forged acceptances to be in Mr. Abraham Rose’s handwriting, and also all the cheques drawn by the defendants”. To him, the signatures on the forged cheques looked no different to those which Abraham had admitted signing. Mr Evans testified that the account had always been satisfactorily run until the discovery of the first forgery in December 1884. Witnesses were called from the Central Bank and the Bank of England to testify and affirm to the fraudulent actions, and evidence also showed that several of the cheques had been given to creditors in payment. It was proved that Mr Rose had opened an account at the City Bank and paid in ₤480 in gold and silver.

In his defence, Abraham denied signing the last bank agreement in 1883, nor did he remember a conversation with Mr Evans regarding the cheque with an irregular signature. He emotionally told the court that “it had been the misfortune of his life that he was unable to handle a pen”, and that his son Alfred kept the cheque books and filled out the details while Abraham only signed them. Alfred had left England telling his father he intended to visit their representative in Holland and he hadn’t been seen since. To exacerbate Abraham’s woes, most of the firm’s books had been destroyed in a fire the previous year. Abraham said he had looked at the cheques paid by the bank after 6th January 1885 and many of them had not been signed by him. He had opened the account at the City Bank with money which he had saved and had in his safe. On cross examination, he reiterated that he could write nothing but ‘A.Rose and Co.’ and his real name ‘Guttentag’. He appears to have been rather naive regarding his books and his bank account, admitting that he never took any notice of his books and expecting the bank to advise him if he ran out of money. He signed cheques put in front of him without question. On re-examination, Abraham admitted that one of the cheques he’d previously denied signing, he had in fact signed.

His son, Alfred Rose, was in Mexico carrying on business as George Guthrie and Co. – Abraham did not know who George Guthrie and Co. were but he had done business with them. He said he’d found their name in a book and had been told they were large merchants so had sent them goods to the value of ₤250. Transactions with them had begun in March 1885 and, the previous autumn, he had sent one of his sons out to visit the company, only to find that George Guthrie and Co. was run by his son Alfred.

Arthur Rose said his father was unable to read and write (although Abraham had previously testified that he had found George Guthrie and Co. in a book) and his brother Alfred had always kept the accounting books. Alfred had first written from Mexico in June or July 1885. The first goods had been sent to Mexico in reply to an order in March 1885. Arthur also admitted that he had, “gone yesterday to the City Bank and taken up a bill of which defendants were drawers and Charles Baker and Co. the acceptors”, thus perpetrating a forgery as he had received the bill from his brother in Mexico.

Sir James Hannen summed up and told the jury that they must decide whether they were satisfied with Abraham Rose’s testimony and whether the cheques were genuine or forgeries. They returned after only a few minutes and found in favour of Central Bank of London.

Abraham was charged with paying ₤2,862 to the bank.

I’d love to know what happened to Alfred, as he sent his daughter back to England to live with her grandfather.

jenoco

Article written from material provided by Val wish Id never started.

© jenoco 2009

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]