Georgette takes a look at the training of the medical professions, with special attention paid to doctors, nurses and midwives, including the surgeons frowned upon for cutting up bodies to learn anatomy and the quack doctors who sold their dubious cure-all remedies.

“In the Autumn of that year (1756) I was afflicted with a dropsy and was under the care of Sr Charles Shugburgh, the physician, and one Curruthers, a surgeon and apothecary, a native of Scotland, who then lived at Stratford. By undergoing a course of blistering scarifying cathartics, dieuretics [sic] and emitics [sic], I was contrary to the expectation of everybody who saw me in my afflictions restored to health about the month of May…I was now got into the tenth year of my age…”

The memoirs of John Jordan of Stratford Upon Avon, 1756 ~ Shakespeare Birthplace Trust Record Office, ER 1/122

John was very lucky to recover considering the methods used to cure him, but the description of how his illness was managed and the people called in to look after him, illustrate perfectly the state of medicine and treatment in the mid 18th century. Physicians, surgeons and apothecaries had very little to offer people apart from bleeding, blistering, potions to make the patient empty himself from both ends and the ‘bark’ to reduce fevers.This last was probably the cinchona bark (later to give us Quinine) from Peru, which was first imported to Europe by the Jesuits in the 17th century. Protestant Northern Europe was very wary of this popish remedy, but an apprentice apothecary in the marshy, fever inducing Fens called Robert Talbor, decided to carry out some trials in an equally marshy part of Essex, using different dosages of the bark to treat fevers and was successful. In 1672 he was appointed King’s Physician in Ordinary to Charles II and set himself up as a fevrologist in London.

The bark became very popular, but also expensive. Many patients thinking that they were taking the magic remedy were actually drinking a fake concoction with the same bitter taste. It wasn’t until 1763 and the work of the Revd Edward Stone of Chipping Norton, Oxfordshire, that white willow bark became used as a cheaper more readily available substitute for treating fevers.

The surgeon, of course, had another arm in his medicinal arsenal, he could always lop off the offending damaged limb or ‘cut for the stone’, but whether or not the patient survived his tender administrations was another matter all together. Anaesthetics did not come into use until the mid 19th century and surgery was considered very much as a last resort.

To become a physician, at the top of the medical profession, a young gentleman went to Oxford, Cambridge or one of the Scottish universities, gained his qualification, an MD after his name and the title of ‘Doctor’. The newly qualified doctor could charge high fees and work in towns or cities, recommending treatments and never getting his hands dirty or preparing medicines himself.

After an examination to check his classical learning as well as his medical knowledge, he could become a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians, founded in 1518. Until 1835 only candidates from Oxford and Cambridge were accepted. It wasn’t until 1934 that the first woman was granted a fellowship, although women had been allowed in as members from 1909. Physicians could be very wealthy indeed and were accepted socially as gentlemen.

With the expansion of the medical profession in the second half of the 18th century, becoming a surgeon was considered a good career move for the son of the gentry or upwardly mobile parents. The surgeon’s status had increased after the separation from the rougher barbers in 1745.

The training, as for that of an apothecary, was by apprenticeship. The premium to cover the apprentice’s food lodging and tuition depended on the success and the reputation of the master practitioner. The premiums asked for increased in line with the demand for medical treatment throughout the early part of the 19th century and surgeons attached to hospitals could expect even higher premiums. All in all, a qualified surgeon once set up in practice could hope to earn a very comfortable living especially if he in turn took in apprentices.

An apprentice would be bound for five or seven years from the age of fourteen to his master. He would live in his house and, at the beginning, would largely be responsible for cleaning the medical equipment and delivering medicines to the patients’ homes. He would follow the master on his rounds and gradually move up to more complex tasks such as preparing medicines and applying poultices. This is what John Taylor had to say of his medical training in 1825:-

“I studied hard; learned the Linnean names and doses of drugs; attended seven surgical operations; worked from nine to nine daily, Sundays included; made up mercury ointment in the old style by turning a pestle in the mortar for three days in succession…drew a tooth for 6d and took 4d if the sufferer had no more…”

If he stayed on to the end of his apprenticeship (John Taylor didn’t, he left to become a lawyer), a young man would then become a journeyman. He could work as an assistant to another medical man or set himself up in practice either alone or with a partner. These men, although called surgeons or surgeon-apothecaries, were actually the forerunners of our general practitioners.

A smaller number went on to further medical training at one of the London hospitals where they would mix with young men apprenticed to the hospital surgeons. They could choose to be a ‘dresser’ for a year or, for a smaller fee, to be a pupil and only attend lectures. Added to these fees would be the extra expense of medical books, equipment and dissection specimens, as well as their board and lodging if they had no family in London. Their days would be spent watching experienced surgeons perform amputations, remove tumours, cysts and kidney stones, walking the wards and attending lectures on surgery, physiology and anatomy.

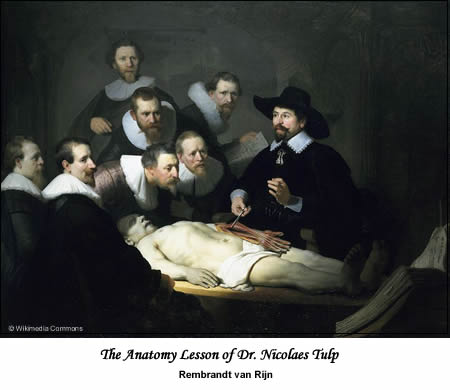

Part of society’s problem with accepting surgeons as gentlemen, lay in their shocking habit of wanting to dissect bodies to further their medical knowledge. Procuring suitable specimens for dissection to instruct the growing numbers of surgeons was a problem. In a country where people still believed in bodily resurrection on the last day, there was nothing so abhorrent as the thought of one’s mortal remains being cut up after death.

Sending the bodies of convicted criminals to be dissected after hanging was considered an extension of their punishment in the same way that gibbeting had been. Unfortunately, there were just not enough hardened criminals to satisfy demand and so a flourishing body snatching industry grew up around the teaching hospitals. The men involved were known as resurrectionists.

Bodies that had already been buried for a few weeks were no good to the hospitals; they needed to be fresh and the fresher the better. The resurrectionists took to stealing bodies from coffins before they were buried, or to paying graveyard watchmen and diggers to tip them off when there were burials. Their activities regularly made the newspapers and there was a genuine fear that, should your loved one’s grave not be guarded for the first couple of weeks after death, their body would be snatched. So, guardians would be paid to keep watch and mortsafes, iron cages erected over the grave, were also used. This is an extract from the diary of John Napier, a resurrectionist, for the year 1811:-

“Thursday 12th December, I went up to Brookes and Wilson, afterwards me Bill and Daniel went to Bethnal Green got 2; Jack, Ben went got 2 large & 1 small back St Luke’s, came home, afterwards met again & went to Bunhill Row got 6, 1 of them with her throat cut named Mary Rolph, aged 46, Died 5th Dec. 1811.”

It makes for fascinating, if grisly, reading. Of course, some body snatchers let their quest for freshness get a little out of hand and they turned to murder. Although Burke and Hare never actually robbed a grave, their first body did die of natural causes and was removed by them from its coffin just before the funeral. They devised a way of killing their victims, ‘burking’ them, by asphyxiation that left the bodies unmarked and so, highly desirable for dissection. It’s known that they killed sixteen people before being caught, but the number may be as high as thirty.

The ‘sterling’ work of the resurrectionists to further medical knowledge, and line their own pockets, was brought to an end by the Anatomy Act of 1832. It stated that unclaimed bodies at hospitals and workhouses would be made available for dissection, so no longer would situations, as described in the satirical ballad “Mary’s ghost. A pathetic ballad” written by Thomas Hood (1799-1845), a humorist and poet, come about.

“You thought that I was buried deep,

Quite decent like and chary,

But from her grave, in Mary-Bone,

They’ve come and boned your Mary.

The arm that used to take your arm

Is took to doctor Vyse;

And both my legs have gone to walk the hospital at Guy’s.

I vowed that you should have my hand

But fate gives us denial;

You’ll find it there, at Doctor Bell’s,

In spirits and a phial.”

At the beginning of the 19th century, hospital surgeon and physician posts were honorary, but they conferred on the holder a prestige that would allow them to ask for high apprenticeship premiums and give them access to wealthy patients.

For other surgeons in the provinces, working for the Poor Law provided them with extra income, as did performing autopsies for the courts. In the surviving records of fees charged, it appears that surgeons, apothecaries and physicians tailored their bills to the financial circumstances of the people they were treating; a wealthy man could expect to pay much more for the same treatment than his poorer neighbour.

Although there was a system in place for medical training, only physicians had recognised qualifications, there was nothing to stop anyone from claiming to be a doctor or a surgeon. Newspaper advertising columns are full of pseudo practitioners offering their patent remedies and treatments right up to the end of the 19th century.

Who could fail to be impressed by “Dr Graham’s Celestial Bed” and its promise to cure infertility or “Godfrey’s Cordial” “Dalby’s Carminative” both guaranteed to treat wind with a hefty dose of opium?

The profession needed to be regulated and standards for education and exams set. The Medical Act of 1858 created the General Medical Council and the Medical Register. At last the profession could distinguish between the qualified and unqualified practitioner and maintain standards by being able to strike any doctor found wanting off the register.

Nurses

Nursing in the 18th century was largely performed by the family of the sick person. If they didn’t have a family member capable of doing the work, the parish would generally employ a woman to tend to them. These women had no qualifications apart from the experience that they had already developed at other bedsides.

With the emergence of voluntary infirmaries and cottage hospitals, women were recruited to act as nurses and matrons. For these posts the most important qualities required were honesty and sobriety rather than nursing skills.

The Matron was in charge of the accounts and keeping her staff in order, much like a housekeeper in a big house, and the nurses were responsible for cleaning and keeping the patients comfortable. Many nurses and matrons at this time were former domestic servants. They lived at the hospitals and their food was also provided for them.

At the London Hospital, which opened in 1740, nurses were expected to work very long hours, “to clean their wards, pewter and utensils every day by seven in the morning”, to make sure the patients took the treatment recommended by the physician and to ensure that they and their beds were clean and tidy. All of this for £6 a year, not forgetting that they should also “behave with tenderness to the patients and with curtesy [sic] and respect to strangers”.

Nursing was beginning to be seen as important, but infirmaries and hospitals tended not to employ enough nurses to care for the number of patients who came to them. Although the nurses’ days were long, they weren’t required to work shifts, as women from the local town or village would be brought in to watch over the wards at night. The importance of having nurses on call at night was not acknowledged until the middle of the 19th century.

When Margaret Winterton was engaged as the new superintendent of nurses in Northampton, in 1889, she wrote an interesting letter to Florence Nightingale describing how difficult the working conditions were. The head nurses had thirty patients in their care on four wards with just one extra nurse during the day and one at night to help them. They were expected to do all the cleaning, as well as looking after the patients and serving their meals. There was no food provided for the nurses so they had to fit their food preparation and meal times into their long and busy days. They worked the day shift one week and the night shift the following week. On Sunday, the change over day, the nurse would do her normal day shift from 6:30am to 7:00 pm, would have two and a half hours off to sleep and eat, and then start her night shift at 9:30pm until 1:00pm the following day.

By the time Mary Winterton wrote her letter in 1889 the requirements for becoming a nurse had changed from, being able to read at the beginning of the century, to having undergone some form of training in a hospital by the second half of the century. By the 1880s formal training for nurses had been firmly established. This was in part due to Florence Nightingale’s influence in helping to change attitudes to accept that nursing was a respectable job for a lady.

As the job description changed from that of little more than a glorified servant, it started to attract educated middle class women who saw it as an alternative to teaching and the newly emerging office work, but nursing was no sinecure. Reading the entry of a nursing probationer in her diary for a typical day in 1890, is exhausting, with her day starting at 7am:-

“7:00 Went on duty. Helped the night nurses’ side; washed two patients.

7:30 Helped on the day nurses’ side; washed a convalescent patient.

8:00 Went to prayers.

8:15 Washed a typhoid patient; washed the urine bottles and the locker tops with chlorinated soda.

8:30 Washed and dusted Sister’s table and window ledges. Cleaned and trimmed the lamps. Washed the urine medicine glasses and small jugs and…”

And so it continued with just a break to attend a class and eat her lunch until the evening:-

“8:00 Carried round the wine and brandies.

8:15 Collected the wine glasses.

8:30 Came off duty.

8:45 Went to prayers.

9:00 Had supper.

9:20 Went to bed”

I bet she slept very well, as probably did her patients after their wine and brandies!

World War One and its need for good professional nurses helped shape the profession further, and in 1919, The Nursing Registration Act was passed setting standards for training, exams and registration. In 1922 the General Nursing council produced its first register of nurses including their qualifications and the place and dates of their training.

Midwives

The face of Mrs Gamp — the nose in particular — was somewhat red and swollen, and it was difficult to enjoy her society without becoming conscious of a smell of spirits. Like most persons who have attained to great eminence in their profession, she took to hers very kindly; insomuch that, setting aside her natural predilections as a woman, she went to a lying-in or a laying-out with equal zest and relish”

Martin Chuzzlewit by Charles Dickens

Midwives had a bad press, it wasn’t just Dickens who liked to portray them as rough dirty women a little worse for drink, but the truth, as ever, is more complicated.

Traditionally a midwife was a widow, as delivering babies was not considered suitable for a spinster. In the 17th and 18th century, midwives were licensed by the Bishop. For this they had to prove their good character and their midwifery skills, as well as being able to pay for the licence. They had no formal training, although many would have learnt their skills at the side of another experienced midwife. In 1671 “The Midwives Book” written by Jane Sharp, herself a midwife, was published.

Her book deals with conception, pain management, care of the mother and child after the birth and technical advice to help with difficult births. It also includes a defence of her profession against the rising popularity of man-midwives where she affirms that women amongst the ‘country poor’ attended by midwives were equally, if not more likely, to have a safe delivery than their richer counterparts who were relying on the help of a male practitioner.

Midwives’ scales of fees, like those of physicians, surgeons and apothecaries, depended on the wealth of the patient they were attending. It wasn’t unusual for the same midwife, if she had a good reputation, to attend the lady in her manor as well as the butcher and labourer’s wife.

She was expected to baptise the baby if there was any chance of it dying and to use her position of confidence to try and persuade the mother to name the father if the child was illegitimate. They held an important place in their communities, some probably delivering several generations of the same family.

When Mary Hopkins of Wilton died in May 1767, her obituary stated that, over the 45 years of her career, she had successfully delivered 10,000 babies and that she would be, “greatly lamented by all who knew her”.

Bishop’s licences for midwives start to decline with the rise of the male practitioner at the beginning of the 18th century and disappear completely by the beginning of the 19th century. The first lying-in ward in a hospital opened its doors at St James’ Infirmary, in London, in 1739. These wards were for married women only and while they became common in London, they were less so outside of it. In fact the situation in London and the rest of the country was very different. In London male practitioners became the norm taking over much of the work of the traditional midwife, but in the rest of the country, although the midwives must have lost some of their work to men, they still continued to practise.

In 1841 the Royal College of Surgeons started examining in midwifery and added a diploma course three years later. In 1886 the Medical Act made having a midwifery qualification essential for inclusion in the Medical Register. All of this, of course, was for male practitioners. Female midwives had nowhere to go for formal training or official recognition.

Several attempts were made during the course of the 19th century to provide adequate training for them, notably by Florence Nightingale and Lord Shaftsbury as president of the short lived Female Medical Society. Things only really began to change at the end of the 19th century with improved education for women. In 1905 a Select Committee called for the setting up of a Midwives Register, the training schools and standard qualifications that went with it. The modern midwife was born.

Georgette

© Georgette 2009

Sources and Further Reading

A Social History of Medicine ~ Joan Lane

The Making of The English Patient ~ Joan Lane

Victorian London ~ Liza Picard

Daily Life in Victorian England ~ Sally Mitchell

Plants against malaria. Part 1: Cinchona or the Peruvian bark.

Civilian nurses