In 2004, Broadmoor Hospital in Crowthorne, Berkshire, deposited their archive with the Berkshire Record Office in Reading. With financial assistance from the Wellcome Trust, the project staff have spent the last four years repairing and cataloguing the collection of over 6000 items. The archive is now available to family history researchers at the record office in Coley Avenue, and to mark this achievement, Reading Museum, which is situated in the magnificient grade II listed town hall, hosted ‘The Secret World of Victorian Broadmoor’ exhibition in 2009.

Until 1800 there was no special sentencing for mentally ill criminals, so when James Hadfield was acquitted of the attempted murder of George III on the grounds of insanity, there was a public outcry. Parliament quickly passed the Criminal Lunatics Act of 1800, so that criminally insane prisoners could be detained indefinitely ‘until His Majesty’s pleasure be known’. Hadfield spent the rest of his life in Bethlem [See: Mental Health and the Lunatic Asylums in this issue], however there were concerns that neither the asylums or the jails were suitable places for mentally ill criminals. Separate wards were built at Bethlem and Fisherton House Asylum near Salisbury, however these soon filled up. The Criminal Lunatic Asylum Act of 1860 allowed the building of the first purpose built criminal lunatic asylum at Broadmoor.

Broadmoor opened in 1863, firstly admitting female patients transferred from other institutions, with men following in 1864. The asylum was isolated and self-sufficient, with 170 acres of farmland and workshops for shoemakers, upholsterers, tinsmiths, carpenters etc, where the male patients would work. The women were expected to work in the laundry, as well as sewing and cleaning.

While the sexes were strictly segregated, their ‘therapy’ was a routine of work, exercise and rest, with newspapers, games, billiard tables, pianos, and a small library all available to them, as well as a chapel for daily services. The patients would play bowls, cricket and croquet.

Broadmoor was managed by a ‘Medical Superintendent’ who along with two doctors were the only medically trained staff at the asylum, whilst about 100 untrained attendants acted as nurses. They all lived on site and would entertain the patients by putting on variety shows in the main hall.

The archive deposited at the record office covers the period from 1863 to 2004, however, due to the 100 year closure rule, only records older than this have been made available to the public.

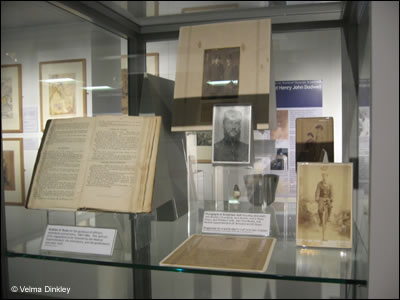

The exhibition displays a selection of artefacts and documents from the Victorian period, such as annual report books, staff record books, patient records, photographs, locks, bolts and keys, and even an attendant’s cap and a spoon marked with the letters BCLA (Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum).

It also focuses on a small number of cases. In particular that of Richard Dadd, an accomplished artist, who was committed to Bethlem in 1843 after murdering his father following a trip to Egypt, during which he became mentally ill. He was transferred to the newly built asylum at Broadmoor in 1864 and continued to paint, dying there in 1886. The exhibition displays some of his work, which is on loan from The Bethlem Royal Hospital Archives and Museum.

Another is the case of Susannah Bradley who, like many of the female patients, was admitted to Broadmoor in 1899 after killing her baby whilst suffering postnatal depression. She remained at the asylum until her release in 1902.

Many thanks to the Berkshire Record Office and Reading Museum Service for their kind assistance in producing this article.

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2009