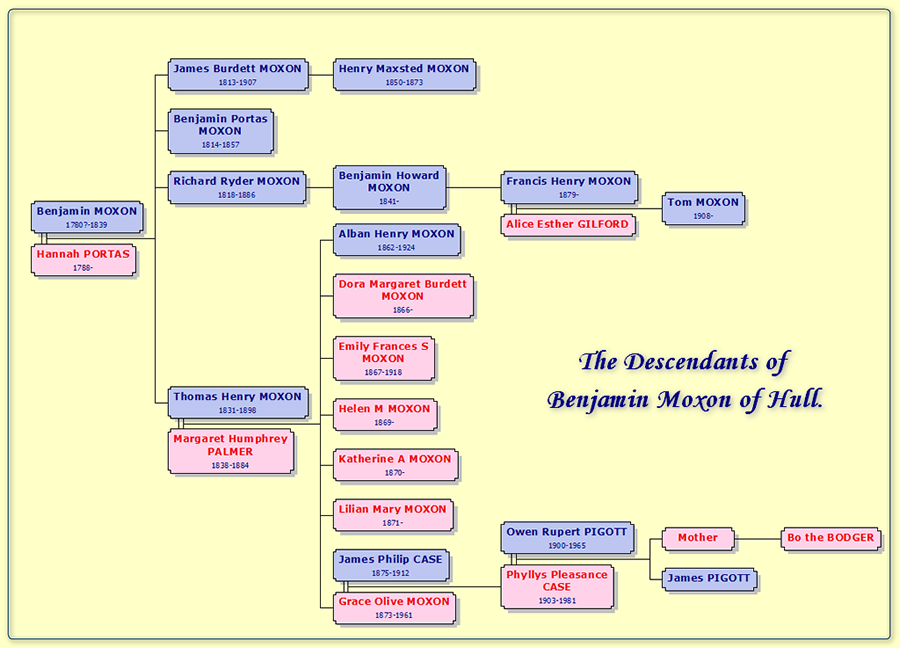

On my maternal grandmother, Phyllys Pleasance Case’s side of the family the medical profession are well represented, however I have only recently started researching this line and they do appear to be very good with the smokescreens which they left behind. The furthest back which I’ve managed to trace for definite is Benjamin Moxon (c1780-1839) who was a druggist/chemist in Hull. He is listed in the 1834 Pigot’s directory as a ‘chemyst/druggyst’ of 22 Market Place, Hull.

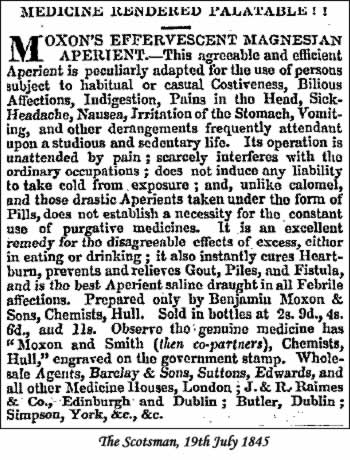

Benjamin married Hannah Portas and they had eleven children: eight sons and three daughters. He went into business with some of his sons and they patented “Moxon’s Effervescent Magnesian Aperient”, an advertisement for which is shown opposite.

At least four of Benjamin Moxon’s sons become medical men – James Burdett Moxon, Benjamin Portas Moxon, Richard Ryder Moxon, and my great x2 grandfather, Thomas Henry Moxon, who was the youngest. Whilst his brothers started off as druggist/chemists, Thomas trained as a doctor straight away, although they would later follow him into the profession.

In July 1847 James was responsible for diagnosing arsenic poisoning in Barnetby-le-Wold, Lincolnshire, in the case of the the infamous Mary Milner, who gave pancakes laced with arsenic to her neighbour, Hannah Jickels, simply because she didn’t like her.

James’ witness statement and testimony were responsible for the defendant being found guilty and sentenced to death. The defendant had tried to wash away the evidence, but he found some on an ash-hill where she had tried to dispose of it and was able to take and analyse samples. He found that there were thirty grains of arsenic, when just twelve was enough to kill a person.

James Moxon had nine children, two sons and seven daughters. At the time of the 1871 census, his youngest son, Henry Maxsted Moxon (born 1850), was recorded as a ‘medical student’, however he died just two years later. I have yet to discover what he died of exactly, but do know that working as a doctor at the time was a hazardous occupation. None of his descendants followed him into the profession. Benjamin junior did not marry and died in 1857.

I have been able to trace the descendants of Richard Ryder Moxon and have discovered that they too worked in the medical profession. Richard’s grandson, Francis Henry Moxon (born 1879), worked as an ophthalmic surgeon and married an Alice Esther Gilford, who had qualified as a doctor in Edinburgh in 1902. She was an active supporter of Emily Pankhurst and the Suffragette Movement, much to the disgust of Francis’ father Benjamin. They had a son, Tom, in 1908 who also trained as a doctor, but sadly drowned in France shortly after qualifying in the 1930s.

I found both Francis and Alice listed on the medical registers on the Ancestry website, although for reasons that I have yet to discover, Alice was only recorded from 1919 onwards. Francis is listed through to 1959, when the site’s records finish. They must have been fairly well to do as the registers show them as living at 4 Bentnick Street, Cavendish Square, London, from 1923 to 1935, then moving to Wimbledon. I also found Francis’ father, Benjamin Moxon, listed up to 1919, when he would have by that time been in his late 70s.

Around the time of the First World War Francis and Alice lived and practiced in Wealdstone, North West London, which was near to where my grandmother, Phyllys, was growing up with her widowed mother, Olive Grace Moxon, so I feel sure that she would have known them and that they influenced her future choice of career.

My great x2 grandfather, Thomas, married Margaret Humphrey Palmer in 1861. They had eighteen children, but to quote my great grandmother, Olive, “never more than eleven alive at any one time my dear”. Through my research I have discovered that there are quite a few instances of where two children were born the same year, and given that he was a medical gentleman you’d think that he would have perhaps known better! Margaret Humphrey Palmer was the daughter of a surgeon and three of her brothers were doctors as well.

Thomas and Margaret’s eldest son, Alban Henry Moxon, was a doctor, and was in partnership with his father at 147 King Street, Great Yarmouth. After his father’s death, in 1898, he moved to the premises of his uncle, Charles Palmer, at nearby 44 King Street.

We were always led to believe that from these eighteen children, our family were the only descendants, especially as Alban was said not to have married. So you can Imagine my surprise when I received Alban’s 1924 death certificate only to discover that ‘his daughter’ registered his death! I have yet to find a marriage for him, and his father makes no mention in his will of grandchildren, legitimate or otherwise.

Three of Thomas’ daughters were nurses: Dora Burdett Moxon, Helen Maria Moxon and Katherine Moxon (known as Kitty). Dora was last seen listed as a nurse on the 1900 Rhodes Island census. She is the one whom an effective smokescreen has been thrown around. In her father’s will, dated 1896, he leaves £500 to,“my eldest daughter Emily Frances Sophia”, as well as stipulating that he was to “leave the residue of my estate to be divided up amongst my five daughters”. However the mystery is that there were six alive at the time. His daughter, Lilian, married a doctor.

Helen and Kitty were both nurses during World War One, along with some of their cousins. It appears from Helen’s records that she was not cut out for hospital nursing and her annual review for the first year was very brutal about it.

Would you employ this person again?

No

Is this person suitable for hospital nursing?

No

If not why not?

Slow, unable to respond in a crisis, doesn’t follow orders well.

However, she was given a glowing personal character reference, saying how well liked she was by both the patients and the staff and what an excellent bedside manner she had. Helen was required to sign the bottom of the form, and added that she fully concurred with the aforementioned assessment.

Kitty was much more successful and trained at the Victoria Royal Infirmary in Newcastle Upon Tyne. She was a theatre sister to two surgeons, one of whom used to wear a frock coat which was so stiff with blood that it could stand up on its own. His dog used to lie underneath the operating table during operations. As for the other surgeon, my mother would say that he “was a bit modern my dear, believed in that new stuff carbolic soap”.

Thomas’ granddaughter and my maternal grandmother, Phyllys Pleasance Case, trained as a doctor in the early 1920s. When she married Owen Pigott in December 1927 they honeymooned in Cannes. They awoke to the headlines in an English local newspaper of “Intrepid Airforce Officer weds Doctor”.

In World War Two Phyllys worked as a RAF doctor at Bletchley Park, the location of the UK’s main codebreaking establishment. My mother has told me that due to the nature of the work undertaken, many people there were inclined to work themselves to exhaustion and nervous breakdowns. To prevent this from happening, some were placed into a medically induced coma for a week so that they could ‘recharge their batteries’.

Both of Owen and Phyllys’ children, the late Francis Pigott and my mother, joined the medical profession. Francis was a consultant anaesthetist and my mother started as a Naval VAD, but undertook her nursing training at St Bart’s, in London, where my late uncle also trained.

She often likes to tell the story of how as junior nurses they were sent into the kitchen, in the dark, to stomp on as many cockroaches as possible and present the bucket to the head matron for inspection, and if she didn’t think that it was full enough then they were sent back in again for another go.

Now, how hospitals have changed!

Bo the Bodger

© Bo the Bodger 2009