My great grandfather, Charles Williams, was widowed and left with seven children in 1906. He remarried in Cirencester, Gloucestershire, in 1907, and as I knew nothing about my step great grandmother, Kate, I set out to discover more about her by firstly obtaining their marriage certificate.

I was surprised to discover that her maiden name was ‘Isenschmidt’ and that her father was recorded as ‘Jacob John Isenschmidt, meat salesman’. This surname didn’t sound like a local Gloucestershire name at all, so I set about tracking him down. I couldn’t find him on the 1901 census, however on looking at the 1891 census, I was intrigued to learn that he was born in Berne, Switzerland, and at the time was living in South London, whilst his wife was living in Holloway, North London.

The IGI confirmed that a ‘Jakob Isenschmid’ was born 20th April 1843 in Buch, Buempliz, Bern, Switzerland, the son of Bendicht Isenschmid and Catharina Pfaffli.

Idly, I wondered if he had ever applied for British citizenship and put his name into the search box on The National Archives website. Imagine my surprise when I found several ‘hits’, all relating to Jack the Ripper and the Whitechapel murders! The National Archives records referred to him as ‘Joseph’, but it was clearly the same chap as his addresses matched and his wife’s evidence was also recorded.

I don’t know when Jacob came to England, but he married Mary Ann Joyce, a farmer’s daughter, in St Luke’s registration district, London, in the last quarter of 1867.

He first appears on the census in 1871, aged 29, with his wife Mary Ann and their eldest child, John Richard, living in Baldwin Street, Finsbury, London. Jacob’s occupation was recorded as ‘head butcher’.

A year after the census, Jacob’s eldest daughter was registered in Holborn registration district as Catharine Annie ‘Isenschmid’ although she later spelt her christian name with a K. I assume that Jacob named her after his mother, Catharina.

By the time of the 1881 census, Jacob and Mary Ann had added three more daughters to their family, Ada (born 1875 Hackney), Annie (born 1878) and Minnie (born 1880 Islington). Jacob was now described as a ‘journeyman butcher’ and the family were living in Kingsbury Road, which still runs north off the Balls Pond Road in Hackney.

According to his wife’s later testimony, Jacob had not been “right in the head” since 1882/3 when he had suffered an attack of heat stroke. In 1887, a year before the Whitechapel murders, Jacob had been committed to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum following threats to his wife. He spent ten weeks there and was then released, pronounced ‘cured’ on 2nd December.

He and his family moved to 97 Duncombe Road, Islington, and Jacob started a new job in Marylebone High Street as a journeyman butcher. However, he soon became so bad that his wife was forced to have him committed once more. I do not have any information about this further period, but Jacob must have been released shortly afterwards. Jacob and his wife then lived separately, with him in lodgings where he prepared meat obtained cheaply from markets to sell to restaurants and coffee houses in the West End of London.

The first victim of the murderer, now known in history as ‘Jack the Ripper’, was Mary Ann Nichols who was murdered on Friday 31st August 1888. A week and a day later, on Saturday 8th September, the second victim, Annie Chapman, was found murdered.

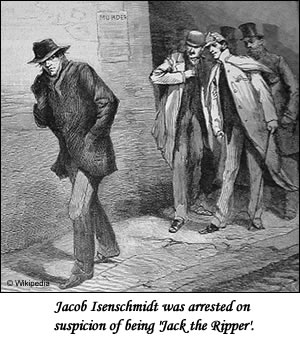

Three days later, on 11th September, two Holloway doctors, Cowan and Crabb, called at Holloway police station with information that Jacob’s landlord, George Tyler, was suspicious about his tenant, who was known locally as ‘The Mad Pork Butcher’. Apart from Jacob’s threatening behaviour, he matched the description of the person with “red hair, looking wild and acting oddly” in Mrs Fiddymont’s pub, the ‘Prince Albert’, in Brushfield Street on the morning after Annie Chapman’s murder. So the next day, 12th September 1888, Jacob Isenschmidt was arrested on suspicion of being the Whitechapel murderer.

Sergeant William Thick examined Jacob’s clothes for bloodstains and interviewed his wife Mary Ann at 97 Duncombe Road. She thought that Jacob wouldn’t harm anyone except herself, adding chillingly, I think he would kill me if he had the chance”. She also said that Jacob had used a public house in Wentworth Street, Whitechapel, but the landlady denied knowing him.

On 18th September, The Star newspaper ran an article based on an interview with Mary Ann Isenschmidt, with which I presume she participated willingly for payment, as she would have been in need of the money. The reporter wrote that, “entirely without any means of support, and is even homeless, since all her goods have been taken by the brokers for rent”. In the article Mary Ann says that her husband had been released from an asylum but wasn’t right and had been so bad, with his frightening violent ‘fits’, that she had got an order for him to be readmitted. However, he had been suspicious about the doctor who came to examine him and ran away to avoid being committed, although she continued to say that he had come back five or six times since then, even though the police had been looking for him. Apparently he was prone to fits of reading the Bible for hours on end and would say, “I must be a very wicked man if all the Bible says is true”

On 19th September the East Anglian Daily Times ran an article entitled “The Holloway Lunatic”, stating that Isenschmidt had yearly fits of madness occurring at the end of the summer, and that he had delusions called himself “The King of Elthorne Road”, the address of which he had at one time kept a pork butcher’s shop.

Inspector Frederick Abberline, the detective in charge of the ‘Jack the Ripper’ case, noted that, “Although at present we are unable to procure any evidence to connect him with the murders he appears to be the most likely person that has come under our notice to have committed the crimes, and every effort will be made to account for his movements on the dates in question.”

Jacob Isenschmidt was still in custody, confined to Grove Hall Lunatic Asylum, when the notorious ‘double murders’ of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes took place on 30th September, thus proving his innocence.

I do not know exactly what happened to Jacob after he was cleared of suspicion, but just three years later he appears on the 1891 census as ‘Jakok Isenschmidt’, aged 48, working as a porter and living in lodgings in Chatham Road, Camberwell. His wife and children were still living at 97 Duncombe Road, although their only son died later that year, creating yet another source of distress and grief.

Jacob was committed to Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum in 1895, and twelve years later his daughter Katherine married my great grandfather, Charles Williams. They didn’t have any children, and whether this was because of a medical problem, or by choice I don’t know. Charles was the nephew of William Mealing, who had murdered his fiancee and spent the rest of his life in Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane [Little Nell has written about this story in The Rendcombe Tragedy]. So one does wonder if they exchanged information about their insane relatives and decided not to take the chance.

Jacob died at the asylum in 1910, with his cause of death recorded on his death certificate as “recurrent mania, lobar pneumonia and exhaustion”. His widow, Mary Ann, died in 1929.

Little Nell

© Little Nell 2009

SOURCES and FURTHER READING

There are hundreds of books about Jack the Ripper, but the one that I recommend is based on the actual documented evidence and contains two photos of Jacob Isenschmidt taken in 1895 and 1896 – Jack the Ripper: Scotland Yard Investigates by Stewart P. Evans and Donald Rumbelow. Sutton Publishing, 2006

For all aspects of the Whitechapel murders, with a wealth of detail about London during the period, check out this excellent website: Casebook: Jack the Ripper