There has always been a proportion of the population who have suffered from mental health problems. However, up until the 20th century, it was a poorly understood subject, with many people sent to the lunatic asylum for a wide variety of conditions. These ranged from schizophrenia and epilepsy to brain tumours and post natal depression, making it highly likely that a family history researcher will find at least one member of their tree who spent some time of their lives institutionalised.

The treatment of the mentally ill

In ancient times, the afflicted were seen as being possessed by the Gods, evil spirits or the devil, as a punishment for their sinful ways. In fact the term ‘lunatic’ derives from being moonstruct by the goddess Luna in Roman mythology. For Christians, diseases of the mind were viewed as a spiritual battle between good and evil, with faith as their only cure.

Attitudes had hardly changed by the Middles Ages, with sufferers despised and ridiculed, blamed for the failure of crops and other misfortunes, and driven from their communities. Ship’s captains would be paid to sail them far enough away, so that they would never return.The lucky ones were those with a family prepared to care, shelter and protect them. They would seek a cure from the church, who would use the healing powers of a holy relic, or would exorcise evil spirits from those considered possessed. An alternative cure would be sought from a physician versed in the Ancient Greek theories that the illness was attributed to the imbalance of the body’s ‘four humours’ of black bile, yellow bile, phlegm and blood. Their treatment would include perforations of the skull known as ‘trepanning’, purges, induced vomiting and bloodletting, to allow the escape of excess humours and evil spirits. Restraining and whipping were also commonplace. During the witch hunts many were persecuted merely for being mentally ill.

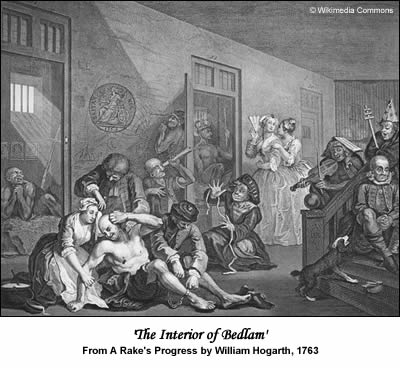

It was under this atmosphere of fear and ignorance that the first asylum, Bethlem, began to admit the mentally ill in 1357, however conditions were insanitary, treatment was brutal and barbaric, with inmates treated no better then animals. In fact, the public were encouraged to come and ridicule, and, literally, poke fun at them.

Private madhouses came into existence in the 17th century, in what became a very lucrative business, with no legislative control until the Madhouse Act of 1774, which required them to be licensed on a yearly basis. Conditions of the inmates varied considerably, with many, mostly the pauper inmates paid for by the parish, suffering cruelty and neglect, shackled in chains and subject to whippings. As a new school of thought was emerging into the causes of mental illness, others were treated more humanely, such as at the Quaker run asylum, The Retreat, in York, which was revolutionary in its approach to treating the mentally ill. [See Merry Monty Montogomery’s article in this issue: Bedford Pierce]

Others were confined in workhouses, jails, houses of correction etc, with their parish of birth picking up the bill.

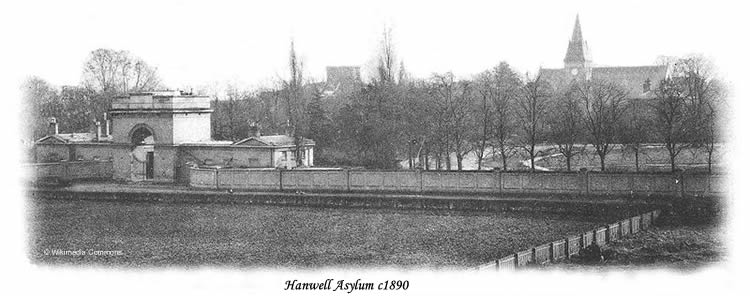

The Industrial Revolution and the subsequent population explosion in urban areas exemplified the need for purpose-built, public funded asylums, for the proper care of the mentally ill. By now, the age old theories of demonic possession were dismissed and these ‘unfortunates’, as they were by now referred to, were considered to be actually ill, and, if treated, could well recover and lead normal lives, and therefore not be reliant on the parish.

The County Asylum Act of 1808 stated that, “Whereas the practice of confining such lunatics and other insane persons as are chargeable to their respective parishes in Gaols, Houses of Correction, Poor Houses and Houses of Industry, is highly dangerous and inconvenient.”

Whilst parish finances were unburdened, local Justices of the Peace were given the power to approve the construction of new asylums, with the local ratepayers expected to pay for them, which of course proved unpopular. A number of new asylums were built, but it wasn’t until The Madhouse Act of 1828, which made the building of county asylums mandatory, that construction of many finally began.

The asylums were built in the countryside in extensive grounds, with music rooms, theatres and libraries, and were self-sufficient with their own farms, laundries and workshops, all considered therapeutic to the inmates. They were to be efficient and disciplined, with the sexes segregated and the harmless/violent and the curable/incurable kept apart, with the intention that those whose condition improved, would in time be released.

Thus began ‘the great confinement’, with large numbers of people suffering from a whole spectrum of mental health problems, as well as those whose behaviour didn’t fit the social norm and those suffering from physical illnesses affecting the brain and nervous system, put together in huge impersonal institutions. For many, the therapeutic benefits of the asylum were wholly ineffective, and with no cure available for their condition, apart from sedatives to calm and placate them, the asylum became their home for the rest of their lives; isolated from the outside world, shunned and ‘forgotten’ by their relatives, and ultimately the place where they were to die. It also wasn’t unknown for cruelty and neglect to prevail in these new, purpose-built asylums.

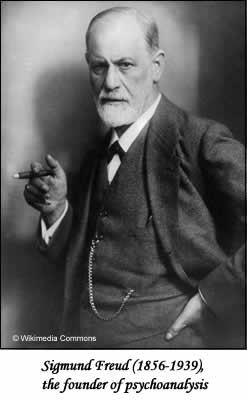

However, it was the concentrating of the mentally ill with a whole range of conditions, that the symptoms of the various syndromes started to be documented, which led to the better understanding of them in the 20th century, influenced by the works of psychoanalysts such as Sigmund Freud, although in later years his ideas fell out of favour.

The understanding of such conditions was further hastened during World War One, when thousands of troops returned from the trenches with ‘Combat Stress Reaction’, otherwise known as ‘Shell-Shock’. Boudicca’s grandfather suffered shell-shock in WW1 and spent the last 27 years of his life in an asylum. You can read her article from the November 2008 issue ~ Traumatised by war.

With greater understanding of the causes and symptoms of these various disorders came new ways to treat them, in particular electric shock treatment, with the shell-shocked soldiers one of the first group to be treated. Other treatments include lobotomies, performed on thousands of patients from the 1930s to the 1950s, and Insulin shock therapy used in the 1940/50s. Viewed by modern day standards, these are seen as barbaric as the bloodletting and whipping of the medieval period, but at the time they were revolutionary.

By the 1950s drugs were beginning to be introduced to treat mental illness, allowing some patients to leave the asylum and lead ‘normal’ lives. Prescription drugs continue to be the treatment for mental illness to the present day, irrespective of the known side effects.

This ‘chemical cosh’ method of treating the mentally ill, was to have an effect on the asylums themselves, as fewer people were admitted and those resident became easier to manage. Their human rights, as well as the cost of caring for them was starting to be re-examined, especially in the light of allegations of institutionalised abuse and neglect. This led to the Government’s ‘Care in the Community’ policies of the 1980s, which resulted in many asylums closing down and being left derelict, where vandals and arsonists ran amok, destroying the heritage of the great confinement era. Most have now been, or are in the course of being, redeveloped.

If you would like to know what a particular asylum looked like, then the best web sites to visit are those of Urban Explorers, such as Abandoned Britain and Derelict Places. Of the asylum records which still exist, most are held in the local county record offices, and these would be the best place to start when researching ancestors who were institutionalised. Records have a 100 year closure on them, although it isn’t unknown for researchers to access more recent documents. To locate such records search under the name of the asylum on The National Archives website. I also suggest that you search for the name of the asylum through Google as you never know what you might find.

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2009

SOURCES and FURTHER READING

Madness, A Brief History by Roy Porter

Wikipedia: History of mental disorders

Index of English and Welsh Lunatic Asylums and Mental Hospitals 1844

Bethlem Royal Hospital

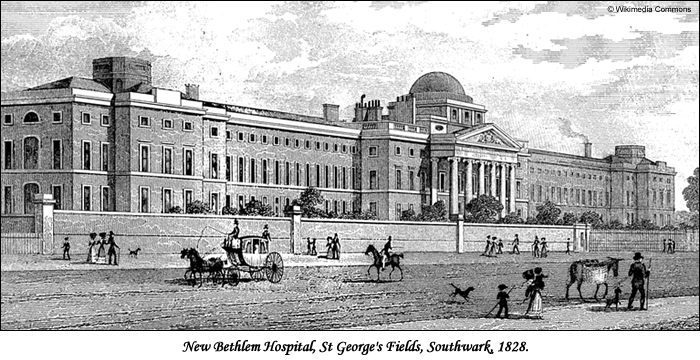

Bethlem Royal Hospital (often referred to as Bedlam) was founded in 1247 as a priory for the sisters and brethren of the Order of the Star of Bethlehem. Its original site, in London, was where Liverpool Street Station now stands. It became a hospital in 1330, and by 1357 it started to admit the mentally ill.

The hospital was notorious for its appalling conditions of filth, brutality and neglect, with the most dangerous and violent inmates shackled and chained to the walls and floors, although the more harmless were allowed out into the city to beg.

In 1675, the hospital moved to new premises at Moorfields and, in 1700, the inmates were no longer referred to as ‘lunatics’, but as ‘patients’, with separate wards for the curable and incurable opened in 1725-1734.

However, this was not to be the start of a new enlightened period in the attitude towards the patients, as the hospital became a tourist attraction, where the public would pay a penny (free on the first Tuesday of the month), to come and watch the antics of the inmates. It became a very popular pastime and visitors were encouraged to bring long sticks, with which they would poke their unfortunate victim in an effort to enrage them. The practice ceased in 1770.

Bethlem moved again in 1815, to premises in St George’s Fields, Southwark, which are now the home of the Imperial War Museum. By now the patients were referred to as ‘unfortunates’ and, whilst the sexes were segregated, their surroundings were vastly improved with an extensive library, a chapel and a ballroom, where men and women were allowed to dance together.

The new premises also included the State Criminal Lunatic Asylum, although patients were moved to Broadmoor Asylum for the Criminally Insane [The Secret World of Victorian Broadmoor] after it opened in 1863.

The hospital’s final move was to Beckenham, Kent, in 1930, and remains there to this day providing mental healthcare services.

The records of the hospital are held in their archive, for more information go to About the Archives.

Velma Dinkley

© Velma Dinkley 2009