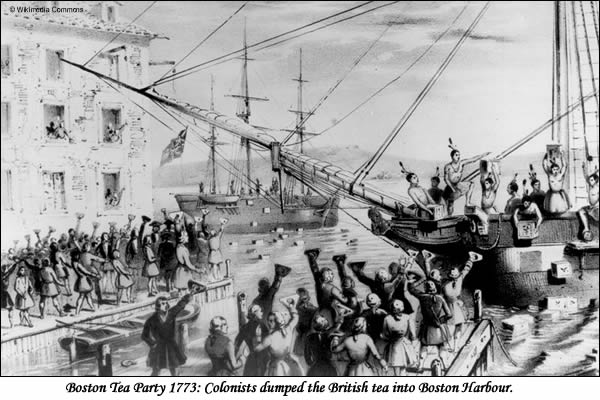

By the 1770s, tension between England and its American colony was running high. The American colonists were becoming increasingly angry at the imposition of taxes, and the straw that broke the camel’s back was the highly unpopular tea tax. The Tea Act of 1773 led directly to the famous ‘Boston Tea Party’, when cases of tea were tipped into Boston harbour.

Trouble (unlike the tea) had been brewing for a long time, and the American Revolutionary War (also known as the American War of Independence) broke out in 1775. The opening stage of the war was the Siege of Boston (19th April 1775–17th March 1776), when the New England Militia (later known as the Continental Army), led by George Washington, besieged the city of Boston, Massachusetts, to prevent the British Army from leaving.

Among the British Army medical officers in Boston during the siege was one Dr Mallet, who had served as a British Army surgeon during the Seven Years’ War. Jonathan Mallet was born in Lichfield, Staffordshire, England, and baptised at St Mary’s Church, Lichfield, on 9th November 1729. His family would have been quite well known in Lichfield; his father and grandfather (both called Jonathan Mallet) were sheriffs of the town, and his grandfather had married a servant of the father of the English author Dr Johnson.

Where Jonathan studied medicine is unknown, but the various stages in his career can be traced in the “Roll of commissioned officers in the medical service of the British army, who served on full pay within the period between the accession of George II and the formation of the Royal Army Medical Corps” [see sources].

He was appointed ‘Hospital Mate, North America’ on 4th March 1756, and received his commission on 31st August 1757, when he was appointed Surgeon to the 46th Regiment of Foot. The regiment suffered terrible casualties at the Battle of Ticonderoga in 1758, and later served in Cuba, where it again suffered battle casualties and disease. Jonathan was appointed Additional Surgeon to the Royal Hospital in North America on 20th March 1759. His appointment was reported in the London Evening Post on 7th August that year.

After Colonel Henry Bouquet’s campaign against the American Indians, which ended in 1764, Jonathan was designated supernumerary on half pay, but returned to full pay in 1766. In 1765 he married his first wife, Catherine Kennedy, daughter of the late Archibald Kennedy, the customs collector of New York. Catherine’s wealthy brother, also called Archibald, who was later to inherit the title of Lord Cassilis from his distant cousins in Scotland, owned a house known as the Kennedy Mansion at No 1 Broadway, New York. The next door house, No 3 Broadway, was left to Catherine in her father’s will, and she and Jonathan lived there with their three children.

In 1775, George Washington’s troops occupied New York, and the Kennedy mansion at No 1 Broadway is thought to have been Washington’s headquarters for a certain period. The British reoccupied the city in 1776, and the property became the headquarters of British Commander in Chief, Sir Henry Clinton. When General Benedict Arnold defected from the Continental Army to the British in 1780, he lived at No 3 Broadway for a while. Whether Jonathan and his family were living there at the time is not known, but they were certainly acquainted with the Arnolds, as Jonathan acted as advisor to General Arnold’s widow, Peggy Shippen Arnold, in London after the revolution, and was appointed her executor.

An image of a 1904 painting showing No 1 Broadway, at the time of the British occupation, can be viewed using this link: Old Print Gallery.

Jonathan, described by contemporary sources as “able and compassionate” and “a gentleman of the utmost humanity”, was appointed Purveyor of the Hospital at Boston, North America, on 11th February 1775, just two months before the siege of Boston began.

In May 1775, he arranged to have a linen factory known as the ‘Manufactory House’ in Boston used as a general hospital for the British stationed there. The main battle of the siege, known as the ‘Battle of Bunker Hill’, was fought on 17th June 1775. The day after the battle, Jonathan wrote to Dr James Lloyd as follows:

Dear Sir,

Your offer of assistance this day induces me to trouble you with this. I mentioned it to the General and he desires me to tell you that it would be the utmost charity to dress the wounded prisoners in the jail. Our people are fairly worn out and cannot possibly attend this duty.

Dr Lloyd, acting on Jonathan’s suggestion, arranged for the wounded enemy prisoners to be treated in the jail by Dr Miles Whitworth. However, many of the prisoners died and blame fell, probably unjustly, on Dr Whitworth, who was imprisoned by order of the Massachusetts Council after the British evacuation and charged with ill-treating and neglecting the wounded prisoners. He died three years later of a fever contracted while in prison.

On 24th January 1776, while the siege was still proceeding, the following appointment was made by the British Army Headquarters in Boston:

The Commander in Chief Appoints Jonathan Mallet, Esq., Chief Surgeon to the Hospital, which appointment he will hold with that of Purveyor.

On 6th July that year the following was published in the London Gazette:

Staff Officers in North America

Doctor Jonathan Mallet to be Chief Surgeon to the Hospital

The entire medical service at Boston was now commanded by Jonathan Mallet, as the British Army’s regimental surgeons came under the direct control of the general hospital as regards medical matters and supplies. Having been appointed Purveyor General and Chief Surgeon of the general hospital, he was responsible for both administrative and logistical problems, a rather unusual situation in the British Army.

Jonathan’s wife Catherine died in 1777, and the following year he married, Mary Livingston Maturin, the widow of army officer, Gabriel Maturin, and daughter of Robert James Livingston, a member of one of the old established New York families. Mary’s family mainly seem to have been Loyalists, including her uncle, Chief Justice William Smith, but one of her brothers, William Smith Livingston, fought against the British with Washington’s Continental Army during the War of Independence, and another uncle, Joshua Hett Smith, was renowned for his part in the conspiracy to arrange the defection of General Arnold from the Continental Army to the British.

A few excerpts from surviving letters of the period give some idea of Jonathan’s duties as purveyor and chief surgeon.

Lord Barrington to Lt.-Gen Gage

1775, March 21 – Mr Mallet, purveyor, to issue pay to hospital mates at the rate of 5s per day, to Mr Fennings, surgery man, at 2s 6d and to Mr Brown, storekeeper of hospital stores, at 3s.

Jonathan Mallett to John George Lorentz

1777, December 21. New York – Explaining the way in which the accounts of the Hessian hospitals must be kept, and the stoppages deducted to show what is due from the Crown.

General Sir William Howe to Jonathan Mallet.

1778, January 19. Philadelphia – Acknowledges letter of 29th December, with enclosure. Desires him to attend to passing Hessian accounts in same form and similar in other respects to the British. Agreeable to treaty he is also to furnish medicines.

Elias Boudinot to George Washington

1778 March 2 – I found the hospitals in tollerable good order, neat and clean and the sick much better taken care of than I expected. This alteration has taken place within a short time past, in a great measure by the industry and attention of Mr Pintard, our agent in New York, who has employed special nurses in the hospitals, added to the supplies for the sick, and done every thing in his power for the relief of the unhappy sufferers (Vid. Dr Mallets letters on the subject of nurses no 8).

Jonathan Mallet to Captain Smith

1780, July 1. Purveyor’s Office, New York – Reasons for the late increased expenses of the hospital department, namely, the unhealthy state of the army last fall which required three new hospitals and medicines, stores and bedding to be purchased.

On 3rd September 1783 the Treaty of Paris brought an end to the War of Independence, and on 25th November the vast majority of the British Army evacuated New York City by ship. Jonathan and his family remained a little longer, perhaps to settle their private affairs or hospital business; a letter written by his wife on 1st July 1784 says that the family had reached London two days earlier, after a six week passage from New York to Dover.

Jonathan was placed on half pay with the rank of purveyor on 25th December 1783, and on half pay on 25th December 1787, with no rank stated. He returned to active service when he was appointed Director-General of Hospitals in America and the West Indies under Sir Charles Grey on 9th October 1793, and was again placed on half pay on 25th December 1794.

Evidently not wishing to settle down to a quiet retirement, on 11th December 1803, at the age of 74, he was appointed Quartermaster of the Volunteer Infantry in his home town of Lichfield.

Jonathan Mallet died at his home in Bryanston Street, London, on 21st November 1806, at the age of 77.

At least eight other members of the Mallet family belonged to the medical profession: A Dynasty of Doctors

Mary from Italy

© Mary from Italy 2009

Notes

- Half pay

Officers on active service received full pay. When not on active service they were not normally entitled to a pension, but could sell their commission and live off the proceeds, or draw half pay, in which case they could be called up for active service as and when required. This often caused hardship, as half pay was by no means a living wage. Jonathan’s statement of the situation, in 1775, supported Lord Barrington’s argument of superannuation for army surgeons, and led to a change in Government policy.

- Purveyor

Purveyors were originally appointed “to perform the duty of butler for distributing the provisions to the sick and wounded”. The purveyor in practice acted as ‘Commissariat Officer’ to the hospital, dealing with the purchase and distribution of food and medical supplies and handling the accounts relating to the matters for which he was responsible.

Sources

Johnston, William. Roll of commissioned officers in the medical service of the British army, who served on full pay within the period between the accession of George II and the formation of the Royal Army Medical Corps. 20 June 1727 to 23 June 1898; ed. by Harry A.L. Howell. Aberdeen, 1917.

Medical Men at the Siege of Boston, April 1775-April 1776: Problems of the Massachusetts and Continental Armies by Philip Cash, Philadelphia, American Philosophical Society, 1973.

Historical memoirs of William Smith, 1778-1783 by William Smith; William Henry Waldo

Johnsonian Gleanings by Aleyn Lyell Reade; privately printed for the author by Percy Lund, Humphries & Co. Ltd., 12 Bedford Square, London WC1, 1939

Sabine, New York Times, 1971

Bouquet’s March to the Ohio: The Forbes Road, from the Original Manuscript in the William L. Clements Library By Great Britain Army. King’s Royal Rifle Corps, Henry Bouquet, Edward Gilbert Williams, Published by Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, 1975

The First Year of the American Revolution by Allen French, published by Octagon Books, 1968

The Kemble Papers by Stephen Kemble, 1885

Palmer v Mallet, Court of Appeal, 1887

Wright’s Directory of Nottingham, 1913-14

UK Medical Registers, 1859-1959 ~ available on Ancestry

Parish Registers, St. Mary’s Church, Lichfield, Staffordshire