John Chapman was born in Loughborough, Leicestershire, on 20th January 1801. His parents were John Chapman, a clockmaker of Loughborough, and his second wife Sarah, daughter of William Parkinson, a farmer who had moved some years earlier from Derbyshire to Quorndon, a village near Loughborough. William Parkinson had converted to the Baptist faith after moving to Quorndon, and he and his brothers were prominent members of the General Baptist Church in Leicestershire and Derbyshire. John’s other grandfather, also called John Chapman, was also a Baptist convert.

Young John was educated in Loughborough, and joined his father’s clockmaking and ironmongery business after leaving school. He soon began to devise improvements to his father’s machinery, learned as much as he could from a local mechanic, and studied pure mathematics in his spare time. He also arranged for a French mechanic employed by his father to teach him French, and taught himself Greek. Books were in short supply in the small town of Loughborough, and John, his brother Edward and some friends decided to remedy the situation. With support from local dignitaries they founded and organised the ‘Loughborough Permanent Library’, which soon flourished.

Like his parents, John was a member of the General Baptist Church, and became a Sunday School teacher when he was not yet 16 years old. His brother Edward organised literacy classes for members of the congregation who were unable to read the Bible. John remained an active member of the Loughborough Baptist Church until he moved to London in 1834.

Rise and fall of the Chapman lace factory

Loughborough was in the heart of the lace-making district of the period, and it was there that John Heathcoat, inventor of the famous bobbinet machine, had his factory (see the article Concrete and Old Lace in the February issue of this magazine). John Chapman’s father often lent John Heathcoat a workman to help him out, and when Heathcoat’s patent expired, John Chapman senior began to manufacture bobbins and carriages for the lace trade on his own account. The lace industry was developing rapidly in France, and Chapman’s products were just what French lace manufacturers needed. The business flourished to such an extent that John junior and his brother William set up their own factory in 1822, and installed a steam engine.

In 1824 John married Mary Wallis, daughter of John Wallis, a lace manufacturer from Loughborough, and sister of Joseph Wallis, tutor of the General Baptist College. During the next 10 years, John became interested in liberal causes, and was involved in promoting Catholic emancipation and the abolition of slavery.

Business was booming, but there was a problem: exports of lace-making machinery to France were prohibited by the English government’s protectionist legislation, so the goods had to be exported clandestinely. At first, the profits were so great that the risk was worth running, despite the occasional seizure of goods by customs officers. However, after some years, demand from France began to decline, partly as a result of a depression and the invention of the new Jacquard and other machinery. The Chapmans and other manufacturers endeavoured to persuade the government to rescind the export ban, but the attempt failed, and partly due to the costs incurred in the appeal process, the Chapman factory was ruined by 1834.

The Hansom cab

Leaving his family behind, John Chapman set off for London to make a new start. He found work as a mathematical instrument maker, and began writing political articles for newspapers. He also wrote for the Mechanics Magazine, and learned a great deal about railways from its pages.

The need was felt at that time for a vehicle available for hire which combined speed with safety. Architect John Aloysius Hansom had designed a new horse-drawn ‘safety cab’, which he patented in 1834, after driving the prototype from Hinckley, near Leicester, to London. The new design was far more stable than the existing hackney cabs, partly due to its huge (7½ ft tall) wheels.

The Safety Cabriolet and Two-wheel Carriage Company was formed to exploit Hansom’s patent, and John Chapman became its secretary in 1836. Hansom was supposed to receive £10,000, an enormous sum at the time, but for reasons which are not entirely clear, he appears to have been paid no more than £300. It soon became obvious that the cabs as originally designed by Hansom were unsuitable for London roads, and John Chapman designed numerous modifications, which he and his financing partner William Stedman Gillett patented in 1836. In particular they made the wheels much smaller, placed the driver’s seat high up at the back of the cab, and placed the doors in the side, to prevent passengers from leaving without paying, as had occurred with earlier back-door models. Chapman and Gillett then licensed their patent to the Safety Cabriolet and Two-wheel Carriage Company. Fifty of the newly-designed cabs were soon plying for hire in London, and the new vehicles were a huge success. The name ‘Hansom Cab’ by which they were originally known stuck, although by rights, the vehicle should have been called a ‘Chapman Cab’.

John Chapman’s wife and children joined him in London in 1836. In 1838 he became deacon and Sunday school superintendent of the Baptist Chapel in Edward Street, London, and later held the same positions in the Praed Street Baptist Chapel. He continued to work for the Safety Cabriolet and Two-wheel Carriage Company for three years, but resigned after disagreements.

The Henson Flying Machine

William Samuel Henson was born in Nottingham in 1812. By 1835 he was working in Chard, Somerset, as a mechanic and lace machinery operator, and had begun experimenting with model gliders and light steam engines with a view to making a flying machine. With John Stringfellow, who made bobbins and carriages for the lace industry, he designed a steam-driven aircraft which they called an ‘Aerial Steam Carriage’. The ‘Ariel’, as it was known, was patented in 1843, although it had never flown (British patent law allowed designs to be patented even if it had not yet been proved that they would work in practice).

Henson and Stringfellow aimed to start an international airline, and publicised it massively in an attempt to raise finance, with colourful prints depicting their plane in imaginary flight over the pyramids and other exotic locations.

In the meantime they conducted numerous experiments in an attempt to perfect the aircraft. In 1844 they enlisted the help of John Chapman, who had developed a whirling arm device. Chapman conducted over 2000 recorded aerodynamic experiments for Henson and Stringfellow, and on the basis of his data they built a model with a 20-foot wingspan, powered by a small steam engine. They tested this model by launching it down a ramp, but it never flew, and the financiers of the project eventually pulled out. The design of the ‘Ariel’ featured many of the elements of the modern monoplane, 60 years before the Wright Brothers made their first flight at Kitty Hawk.

Excerpt from Henson’s patent no. 9478

The Great Indian Peninsular Railway

John Chapman was also a respected writer, and helped with the management of the Mechanics’ Magazine, the Railway Times, the Shareholders’ Advocate, the Mechanics’ Almanac, etc, as well as contributing articles to newspapers like the Times.

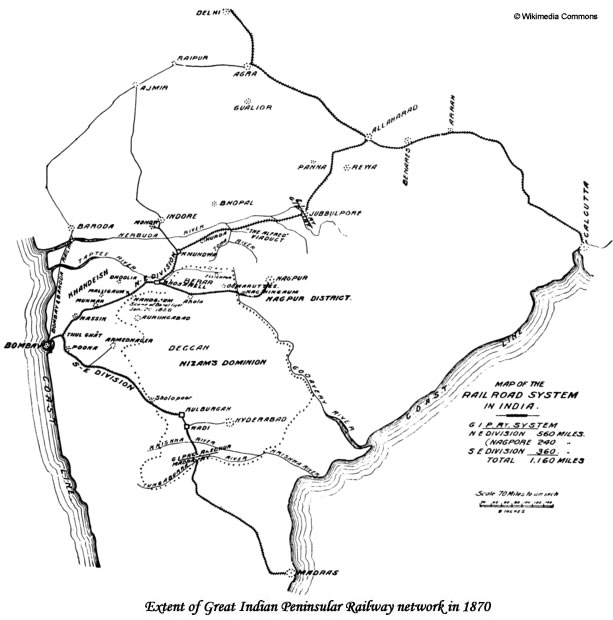

In 1842 he was commissioned by George Thompson MP to report on the position of India and its trade. Chapman took the view that transport was crucial to solving the problem of poverty in a country with a wealth of resources, and in 1844 he submitted a project for constructing the Great Indian Peninsular Railway to the Board of Trade. He was initially ridiculed, but after three years’ hard work and lobbying, the Great Indian Peninsular Railway Company was founded. When the company’s prospectus was published [Advertisement], John Chapman was listed as manager and Robert Stephenson as consulting engineer. Chapman was sent to India in 1845 to make preliminary investigations; he returned to England in 1846 with a detailed report, and his plans were approved by Robert Stephenson.

All this time Chapman had been living from hand to mouth, as no terms for his employment had been agreed. In 1849, after disagreements with the directors, Chapman was dismissed. His claim for remuneration for his services was referred to the East India Company for arbitration, and he was granted a single payment of £2,500. Despite this setback his interest in India continued, and he prepared a major irrigation project, which was approved by the Government shortly after his death.

Death of John Chapman

In August 1854 John Chapman paid a visit to his home town of Loughborough to attend the jubilee of the General Baptist Sunday Schools, and then returned to London, where a cholera epidemic was raging. He was taken ill on 10th September, and died the next day, aged 53. He was buried at Kensal Green Cemetery in London, where six of his children had already been laid to rest.

Mary from Italy

© Mary from Italy 2009

Sources

Memoir of the late John Chapman Esq. (of London) The General Baptist Magazine, 1856

The Chapman Papers: a note on the Hansom cab W.A. Young and A.A. Gomme, 1944

Wheels: A Pictorial History Edwin Tunis, JHU Press, 2002

Inventing Flight John David Anderson, JHU Press, 2004

Across the Borders: Financing the World’s Railways in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries Günter Dinhobl and Ralf Roth, Ashgate Publishing, Ltd., 2008